[ad_1]

“I assume you’ve heard the Aretha story,” said “Divas Live” producer Sean Murphy. He was one of a handful of people I spoke to for the 20th anniversary of the all-star VH1 concert series earlier this year. And yes, I’d heard the Aretha story. It was one for the history books, cementing her position as pop’s OG diva.

In its proper denotation, “diva” means “goddess.” That definition is sometimes lost in the word’s postmodern permutations, where it’s become a shorthand for “bitch.” We all know there are better synonyms: conquerer, artiste, doyenne, Aretha.

As popular music grew in spectacle throughout the 20th century, the personalities of the women making it got bigger. But none would be here without Aretha Franklin, the soul sister who died Thursday at the age of 76. Franklin made divadom possible, first by showcasing an impossibly fierce voice and later by demonstrating an awareness of just how valuable that voice was.

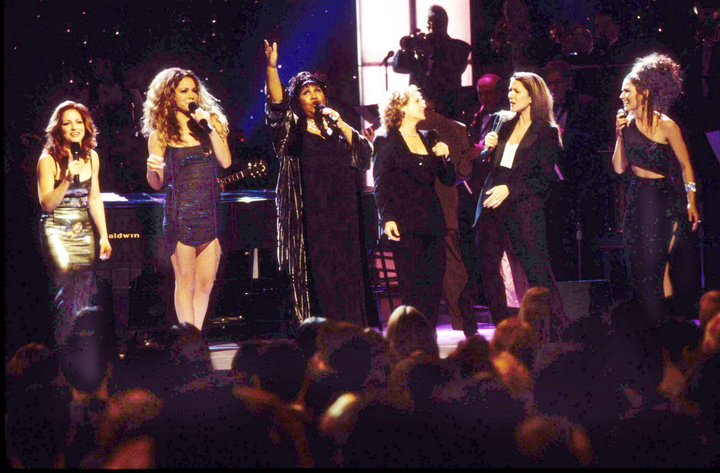

Take, for instance, “Divas Live,” which launched in 1998 with Franklin as the centerpiece. Four decades into her career, no female singer was more exalted than Franklin, even though she hadn’t had a Top 10 hit since 1985. Mariah Carey, Céline Dion, Gloria Estefan, Shania Twain and Carole King paid their respects on that April night, competing for a morsel of the star power that Franklin’s pipes summoned.

KMazur via Getty Images

But it’s not enough to know that our pop matrons are talented. We want to know they’re in charge, that they have battled the forces of sexism and voyeurism and emerged unscathed. In that, “Divas Live” was Franklin’s ultimate crucible.

The “Aretha story” goes like this. Back in ’98, Franklin’s management had apparently instructed the producers to shut off the concert venue’s air conditioning during her rehearsal. It was bad for the vocal chords, they insisted. But when Franklin stepped onstage to run through her numbers, she demanded silence. Placing her hand near a vent, Franklin discovered a breeze was indeed wafting through the room.

“She threw a hissy fit and walked out of the backstage into a car and left,” producer Wayne Isaak said.

Chaos ensued. Was the AC system actually on ― and, if so, why? According to Murphy, the Beacon Theatre was coincidentally running a test of its ventilation that day, so yes, it was on. According to producer Lauren Zalaznick, however, the AC was so off that “the other performers were horrified” by the saunalike environment. Either way, frenzied phone calls followed, and no one was sure whether Franklin would be back for the telecast.

Eventually, the staff learned that Franklin had fled to her hotel, where she was cavalierly snacking on powdered donuts during a dress fitting. Was it a sign that Miss Franklin, as everyone called her, would arrive for the live show without a rehearsal? “Divas Live” was a multimillion-dollar broadcast, and what mattered most was everyone showing up for their cues.

“Things were coming down from Mount Sinai,” Zalaznick said. “We didn’t know [if she’d return], and then all of a sudden the clouds parted, the tablets were delivered, and suddenly we knew. To me, it felt that mysterious and insane.”

The show would not only go on; it would become a hallmark of Franklin’s career, generating a massive audience that saw Franklin’s heirs pay tribute to their diva forerunner just two months after the Lauryn Hill collaboration “A Rose Is Still a Rose” rechristened her relevance among younger music fans. During the evening’s grand denouement, the ladies performed Franklin’s signature “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” written by King, together ― a pageant that’s still better described as Aretha and her five backup singers.

“I think we put the house AC on and froze it as best we could,” Zalaznick added. “And I’m telling you I believe that we cut the AC before Aretha Franklin came out to perform, and maybe again for the finale. Or maybe we said we did but we didn’t.”

Hearing stories like this, Franklin’s sense of authority rings even louder given how little we knew about her personal life. Usually the dignitaries thought to be the fussiest are the ones whose relationships and private behavior headline tabloids. But with Franklin, it was almost always about the music. She positioned herself as culture’s supreme superstar to mask any self-doubt she might have felt as a result of body-image struggles or her two divorces, one of which involved domestic abuse.

In the 21st century, the less Franklin performed, the more candid she became about the counterparts who succeeded her. When Beyoncé introduced Tina Turner as “the queen” at the 2008 Grammys, Franklin took offense, releasing an unprompted statement in which she dismissed it as a “cheap shot.” In 2014, she praised Adele, Alicia Keys and Whitney Houston but offered “no comment” when asked about Nicki Minaj and left Taylor Swift’s plaudits at “great gowns.” In 2017, she sent The Associated Press a fax to clarify Dionne Warwick’s “libel” ― the claim that Franklin was Houston’s godmother.

For Franklin, everything was about status. No one could speak for her, and no one could challenge her sovereignty. As absurd as the whole “Divas Live” episode might seem, why wouldn’t she storm off when her specifications weren’t met? A handful of singers with tighter faces and broader radio play were waiting in the wings to threaten her throne ― or at least that’s what it must have felt like.

And so, on that holy night, in the ultimate diva move, Franklin did what she best knew how to do, as someone whose pioneering spotlight shined long before MTV and TMZ brought celebrity culture to our fingertips: She sang so loudly, so powerfully and so beautifully that no one could compete.

She commanded respect ― and not just a little bit.

ABC Photo Archives via Getty Images

[ad_2]

Source link