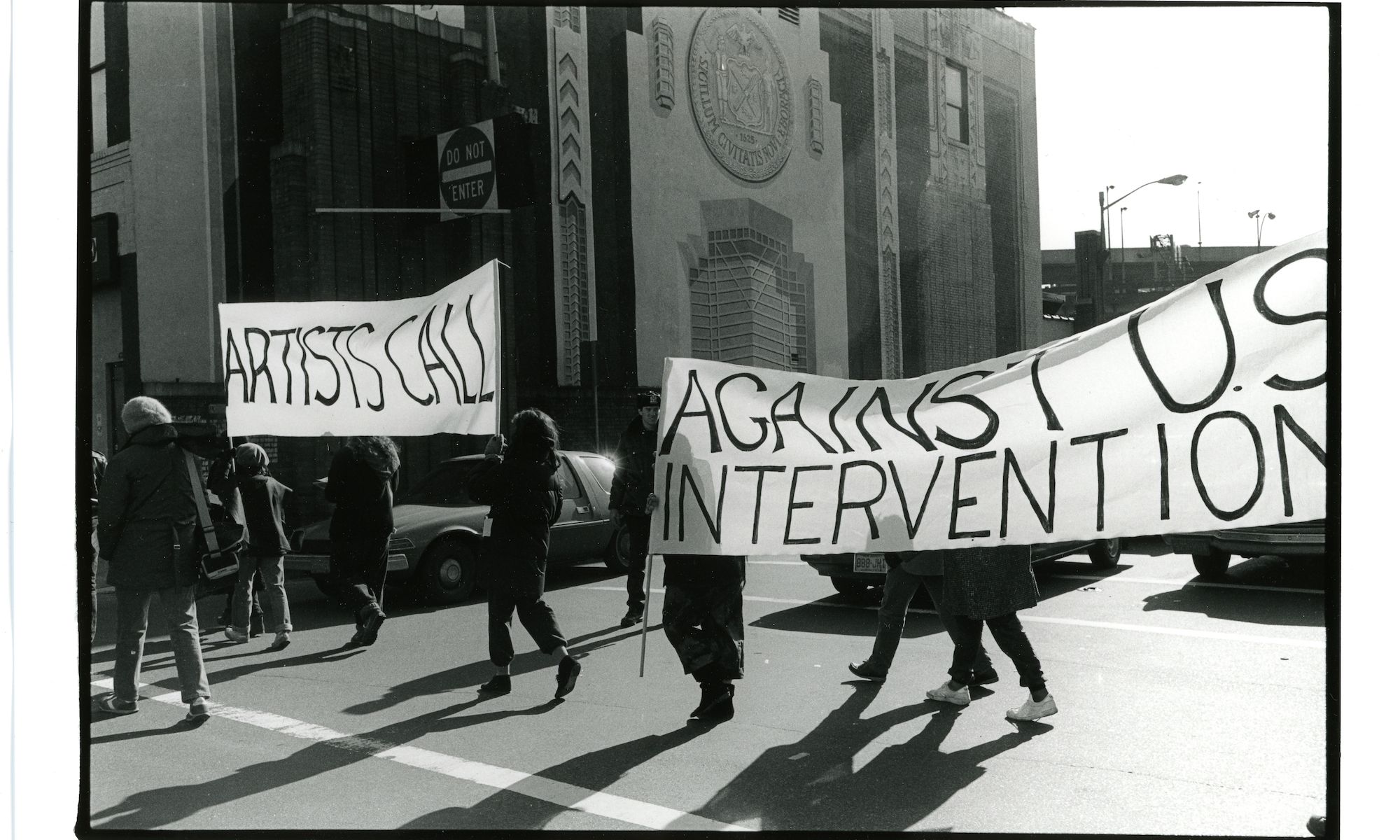

Dona Ann McAdams, Procession for Peace with Artists Call banner, New York City, 1984 Courtesy of artist

Artists Call, an often-overlooked activist movement formed to support Central American artists during a period of social and political upheaval in the 1980s, is finally getting the scholarly treatment it deserves with a two-part exhibition and bilingual catalogue organised by Tufts University Art Galleries in Boston and Medford, Massachusetts. The show, Art for the Future: Artists Call and Central American Solidarities (20 January-24 April), came together when one of its curators stumbled on a surprise trove of documents and works related to the group deep in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art’s library in Queens.

The group Artists Call and its short but significant swell of activity has been a subject of interest for the show’s co-curator Erina Duganne, associate professor of art history at Texas State University, since she first came across a show organised by the artist-run conceptual collective Group Material. “But there was very little archival material on it,” Duganne says.

One of the few results she found online was connected to the PAD/D (Political Art Documentation and Distribution) Archive at MoMA’s library. “I was there in the summer of 2015 and the archivist said, ‘Well, you know, in the back there are these boxes related to Artists Call,’” she remembers. “So I went back with him and there are these 12 boxes and I couldn't believe it. They had just been sitting there.”

Claes Oldenburg in his studio discussing his poster design for Artists Call Against US Intervention in Central America with Jon Hendricks and Margia Kramer, 1983. Photograph by Gianfranco Mantegna, courtesy of Doug Ashford

How the material ended up at MoMA remains a mystery but based on the handwriting found on it, it was likely preserved by the artist Coosje van Bruggen, who was a key figure in the group, and whose husband Claes Oldenburg designed Artists Call’s most recognised poster. Duganne brought in the artist Doug Ashford, another member of the group, to inspect and help identify the materials, and it soon became clear that this unexpected art historical treasure would need to be turned into an exhibition. Especially while influential figures involved in the movement are still alive.

In fact, since she started planning this exhibition with Tufts curator Abigail Satinsky five years ago, three artists who were part of Artists Call have died: Tim Rollins, Serena Lotty Rosenfeld and Jimmie Durham. “So there's just a sense of urgency to give recognition to this campaign that has essentially been forgotten,” Duganne says. “It was this moment that's just gone, erased from our memory.”

Artists Call organizational meeting at Leon Golub and Nancy Spero’s studio, New York, 1984. Courtesy of Doug Ashford

The reasons the movement has been so overlooked are likely due to its brief existence—the main New York group was only active for about a year, starting in January 1984—its lack of hierarchical leadership, and the growing importance and focus on Aids activism around the same time. But in that short window, Artists Call organised dozens of benefit exhibitions and performances in New York involving more than 1,000 artists, including a poignant protest march in which participants carried the names of hundreds of those who had been “disappeared” during the conflicts in Central America.

It also sparked interest from artists and organisers across the country, with chapters of the movement started in 27 other US cities. “It really touched something. I think that made it more of a national movement,” Satinsky says, adding that its relevance to contemporary artist-led social justice initiatives is clear. “These things have long histories that we can learn from.”

Susan Meiselas, EL SALVADOR, Arcatao, Chalatenango province (1980). The "mano blanca" signature of the death squads left on the door of a slain peasant organizer. This work was exhibited in From Central America at Central Hall Artists Gallery in New York. Courtesy of the artist

Similarly, there are obvious historic parallels to be seen between the humanitarian crises in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala during the 1980s and 90s, caused by earlier US political intervention, and the current crisis at the US-Mexico border as immigrants from South and Central America flee worsening conditions in their home countries to find refuge in the US. “This moment where you see the New York art world coming together in solidarity with Central American self-determination and agency is so important,” Duganne says. “That offers a model for today as well.”

The show also raises questions about how history is preserved and the challenges around this. In addition to the material found at MoMA for example, Duganne and Satinsky have also borrowed documents and works from the personal archives held by Ashford and the art historian Lucy Lippard, who was another key figure in the group. But when it came to sourcing material from Daniel Flores y Ascencio, one of the main artists working in El Salvador at the time, there was not much he had been able to hold onto. “The ways in which people are able to save things speaks to the precarity of different people’s positions as well,” Duganne says. “If you’re forced to move a lot, if you don’t have resources, it can vary greatly in terms of being able to keep something or not.”

Hans Haacke, US Isolation Box, Grenada, 1983 (1984). Wood planks, hinges, padlock, spray painted stencil lettering, built by Jeff Plate. © Hans Haacke and Artists Rights Society

Also, many of the works created through Artists Call initiatives were sold off in gallery exhibitions to raise money for artists in Central America, or not intended to remain as objects that would enter the art market. One such example is Hans Haacke’s US Isolation Box, Grenada, 1983, which the artist had built based on a description in the New York Times of the wooden crates used by invading US troops to imprison revolutionaries involved in the overthrow of Grenada’s government that year. The controversial invasion ordered by then president Ronald Regan had broad support in US media, but was internationally viewed as an example of American aggression and a violation of international law. After displaying it at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, Haacke destroyed the work, but it will be recreated for the exhibition at Tufts. “It’s the work that probably received the most response in the press” at the time, Duganne says. “Hilton Kramer attacked it for being Communist.”

Spread across two venues—Tufts’s Aidekman Arts Center on itsmain campus in Medford and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts in Boston—the exhibition includes works by more than 100 artists, including Josely Carvalho, Jimmie Durham, Louise Lawler, Ana Mendieta, Tim Rollins and KOS, Claes Oldenburg, Martha Rosler, Juan Sánchez, Nancy Spero, as well as contemporary responses to the movement by artists such as Muriel Hasbun, Beatriz Cortez and Naeem Mohaiemen.

Dona Ann McAdams, Elena Alexander in Uncle Sam at performance festival, Taller Latinoamericano, 1984 Courtesy the artist