[ad_1]

Is technology closely watching us, or are we closely watching technology? This year, the boundaries grew even thinner between machines and people—AI is grading tests in classrooms across the country, a popular Russian face-aging app sparked widespread panic over data privacy. In July, a Florida judge granted police access to GEDmatch, a widely-used DNA database similar to Ancestry. These developments were reflected in the art world, where artists and auction houses experimented with the possibilities of technology, museums launched new digital platforms, and new apps were made. What follows, in no particular order, are some of the year’s defining art-and-tech initiatives.

Christie’s Aims to Make History With Sale of First Mixed-Reality Work

AI-generated works and virtual reality pieces were long thought by many to be impossible to sell, but auction houses are pushing forward, making available works involving new technologies with aplomb, and next year, a new precedent could be set. In 2020, Christie’s will sell the first mixed-reality work ever to hit the auction block: Marina Abramović’s The Life. (Mixed reality differs from virtual reality in that the surrounding environment is still visible, even with while wearing a headset.) The sale of was announced in November after the work debuted at London’s Serpentine Galleries. The 19-minute piece features Abramović pacing around, occasionally flickering in and out of vision, and it was met with reviews that were less than positive—Guardian critic Jonathan Jones wrote, “I’ve only experienced events this vacuous at really bad concerts.” But the auction house seems hopeful that the work will be bought for somewhere in the range of $775,000, with the buyer will receiving a recording of the piece and “wearable spatial computing devices,” according to Christie’s. The piece could set a new auction record for Abramović—and change the state of digital works on the market.

Guy Bell/Shutterstock

Alan Michelson Reveals Ugly Parts of American History Through AR

For his solo show at the Whitney Museum in New York, Alan Michelson, a Mohawk member of Six Nations of the Grand River, created four works that explore the impact of colonialism on Indigenous peoples and the destruction of the land on which they live. The show included two augmented reality works, both produced with the help of artist Steven Fragale, that can be accessed through an app. When one of those AR works, Sapponckanikan (Tobacco Field) (2019), is activated, a circle of tobacco plants indigenous to New York appears on one’s phone screen, looking as though it had sprouted through the floors of the Whitney’s lobby. And, when viewed through the app, Town Destroyer (2019) reveals a three-dimensional bust of George Washington overlaid with moving images and audio relating the story of the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign of 1779, a scorched-earth invasion of the Haudenosaunee homelands ordered by the founding father. Michelson’s new pieces are AR works at their best—they reveal the unpleasant realities of our own world that are often kept out of sight from many people.

Courtesy the artist

Moscow’s Garage Museum Launches a Pioneering Online Art Platform

In December, the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow launched Garage Digital, a platform for digital artworks that could become a major resource for artists and the public alike. Through it, curators at the museum will commission new artworks, and research materials—including documentary videos and academic studies—will be made available. Currently, Garage Digital is hosting new artworks by Sascha Pohflepp with Matthew Lutz and Alessia Nigretti, Gints Gabrāns, and James Ferraro and Ezra Miller; the museum has promised more to come in the future. There will also be a focus on gaming, and among the offerings on the website right now offers gameplay of Hideo Kojima’s Death Stranding (2019), one of the year’s most eagerly awaited video games which stars renders of Norman Reedus and Léa Seydoux. This isn’t the kind of material typically made available by an art museum, and it’s an example of how open-minded and essential Garage Digital could soon become.

Apple

[AR]T Walk Brings Augmented Reality to Midtown New York

There were words in the sky around New York’s 59th Street. They fell and faded, seeming to melt away into the landscape around them. This was real life, or something like it—an AR poem by the late artist John Giorno called “Now at the Dawn of My Life,” part of [AR]T Walk, which was started by Apple and the New Museum in New York. Not unlike Pokémon Go, participants could point iPhones—loaned by Apple and loaded with the [AR]T Viewer app—at predetermined locations and view large-scale artworks become visible. The results left something to be desired—none were particularly memorable—but the talent that the initiative had enlisted, which included artists such as Nick Cave, Nathalie Djurberg, Hans Berg, Cao Fei, Carsten Höller, and Pipilotti Rist, was impressive.

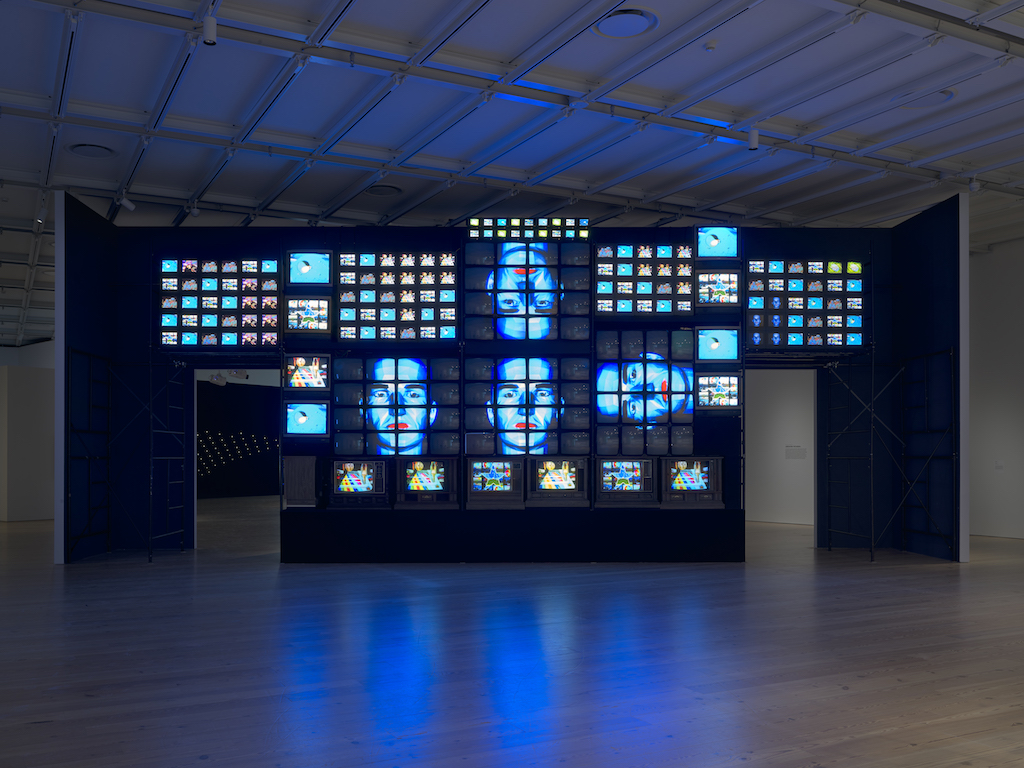

“Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018” at the Whitney

From foundational works of Minimal and Conceptual art, like a Sol LeWitt wall drawing from 1976, to a restored version of Nam June Paik’s hypnotic video wall Fin de Siècle II (1989), to several digital works recently commissioned by the Whitney, this show, which opened in 2018 but closed in 2019, charted the ways systems, mathematics, and choreographies have altered art dealing with technologies. Curated by Christiane Paul, the show included some of the best works making use of technology in recent years, among them Mendi + Keith Obadike’s The Interaction of Coloreds (2002/18), which allows users to determine the correct HTML coding for their skin tone by filling out a questionnaire which included prompts such as, “Has your skin color ever been in vogue?”

Dan Bradica

Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Shadow Stalker Tells Us About Ourselves

A pioneer in her field, Lynn Hershman Leeson has long questioned what separates our bodies from cyberspace and the surveillance state. Shadow Stalker, her latest work—now on view in the Shed’s “Manual Overdrive” show—deals with the practice of data mining, in which personal information is collected online by entities and corporations, often in ways that are not immediately disclosed to the users themselves. Hershman Leeson’s installation uses technology similar to the predictive policing system deployed by American law enforcement departments to gather data that could forecast where future crimes will occur. (Such practices have been controversial, with some alleging that officials have used them to target low-income and predominantly nonwhite communities.) At the Shed, viewers are invited to enter their email address, and Hershman Leeson’s algorithm fetches chilling results: old home addresses, the names and prior locations of loved ones. It’s a creepy work about the uneven power dynamics that guide the way we use digital technology—and an instructive one about the dangers of putting too much information into our beloved machines.

[ad_2]

Source link