[ad_1]

Stephen Tayo, Lagos, Nigeria, 2019.

©STEPHEN TAYO

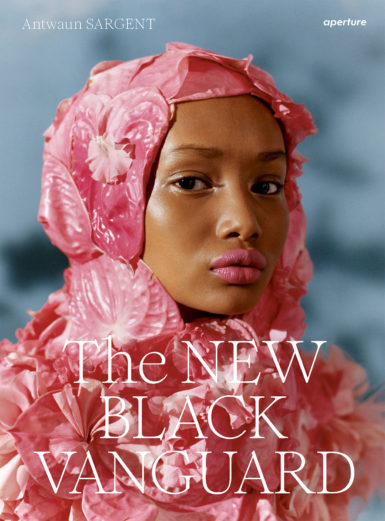

It took the art world decades to consider photography an art form, and it took even longer for critics, curators, and historians to think of fashion photography in terms of art. Despite those long-overdue shifts, most of the fashion images regarded artistically have come from white photographers. Antwaun Sargent’s new book, The New Black Vanguard (Aperture), offers a new approach to that history, with a consideration of 16 young black fashion photographers that focuses on how they think through black identity today. It is accompanied by an exhibition that he curated of their work and related photography that opens at the Aperture Foundation in New York on October 24.

To learn more, ARTnews spoke with Sargent, who wrote a profile of Top 200 Collectors Kasseem “Swizz Beatz” Dean and Alicia Keys for the current issue of the magazine that features photography by Dana Scruggs, one of the subjects of his book.

ARTnews: How did the idea for The New Black Vanguard originate?

Antwaun Sargent: The central argument is that there’s a new movement in photography being led by a group of young international black photographers who are working in a commercial context but are influenced by photographs and photographers who have existed primarily in an art context. They’re doing that through the language of fashion, which I find really interesting, given the fact that fashion photography is the biggest stage in all of photography.

COURTESY APERTURE

You get the sense that these artists are operating in different contexts and thinking in different ways. Stephen Tayo, who primarily shoots lightly staged street-style photography, starts shooting with an iPhone, and he starts shooting because he didn’t have images of himself from childhood. He wanted to create that sense of history through the photograph for others. And then you have someone like Awol Erizku, who exists on the opposite side of the spectrum. He went to Cooper Union and Yale, and is thinking about photography in a highly conceptual way, with such a sense of art history. He’s thinking about painting—with Girl with the Bamboo Earring [2009], he draws on Vermeer and Dutch and Renaissance painting. And you have Tyler Mitchell, who’s thinking about the American South in a way that, say, Roy DeCarava thought about Harlem—how do you use photography to mirror your reality? He comes from a middle-class black suburban community outside Atlanta, and he wanted to show how that could be seen, too. And you have someone like Renell Medrano, who studied photo at Parsons and is thinking about the Bronx and femininity.

The way most of us come into contact with photography is through a commercial context. We’re thinking about magazines, we’re thinking about billboards. With shifts in technology, shifts in publishing, how are those images living, and how was I encountering those images? I kept seeing, on my social media feeds, these young black photographers making their own images and often publishing them on their own platforms, outside traditional magazines, as a way to circumvent [and] show their concerns without being mediated.

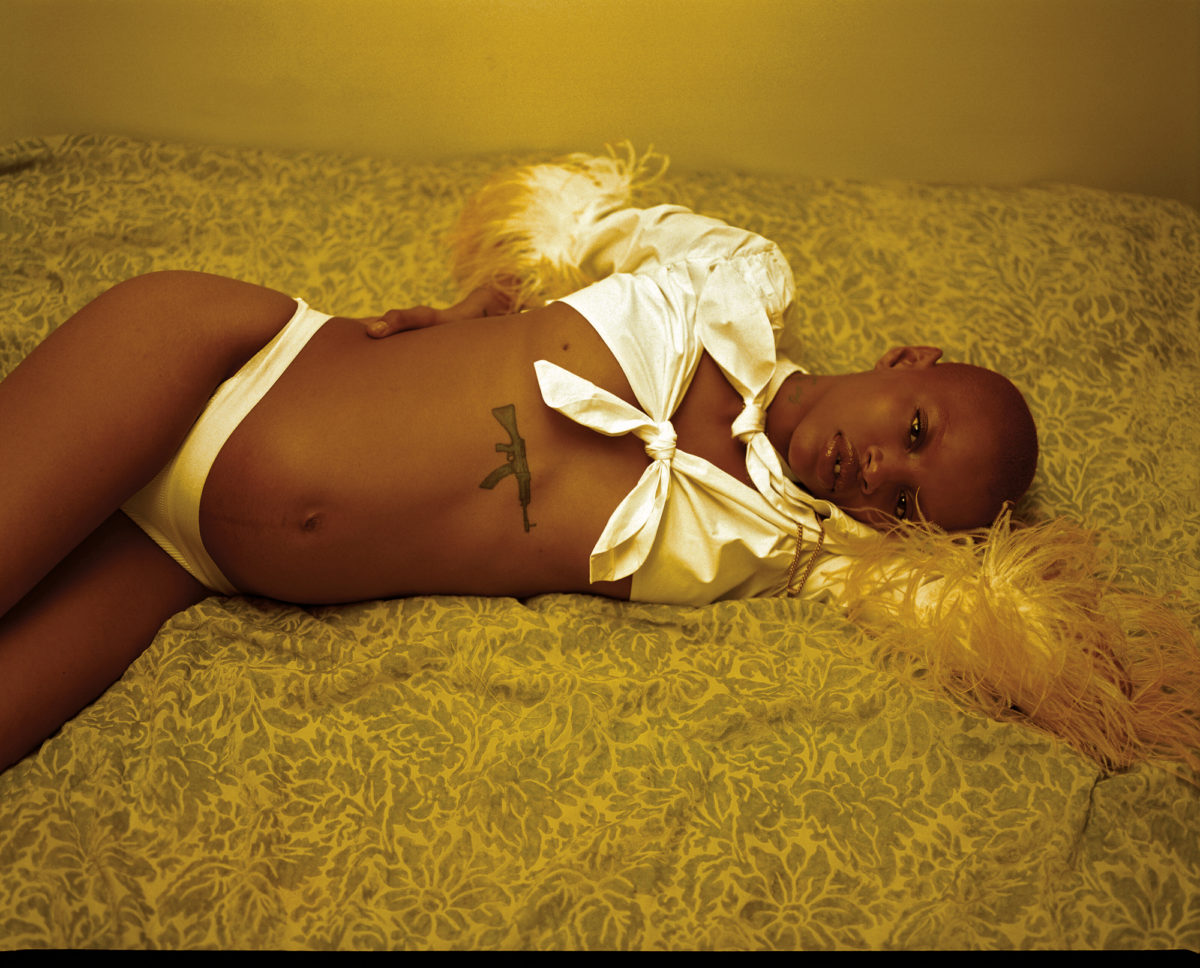

Renell Medrano, Slick Woods, Brooklyn, 2018.

©RENELL MEDRANO

Most histories of fashion photography skew white and male. Was this book meant as a corrective?

This book is almost half female. Often the desires that we see in photography are the desires of men, so when we consume photos, we’re consuming the desires of men. That was also an important thing to think about: How are women considering histories of race, photography, fashion, and self-representation?

That calls to mind a quote from the photographer Ayana V. Jackson about “fighting photography with photography” and her idea that black photographers could create pictures that highlight how photography was built for white sitters—something that scholar Sarah Lewis has addressed. Are these photographers thinking of their work in that way?

Too often we’ll say something is about blackness, but what we’re really doing is still centering a white gaze. What’s special about these photographers and this movement is they’re creating the images they want to see in the world. Often, if you pay attention to credit lines, they’re doing that with black designers, stylists, and hair-and-makeup artists—so it really is a black world. It’s a reaction to whiteness, but that’s not the whole thing. These images are not about a white gaze.

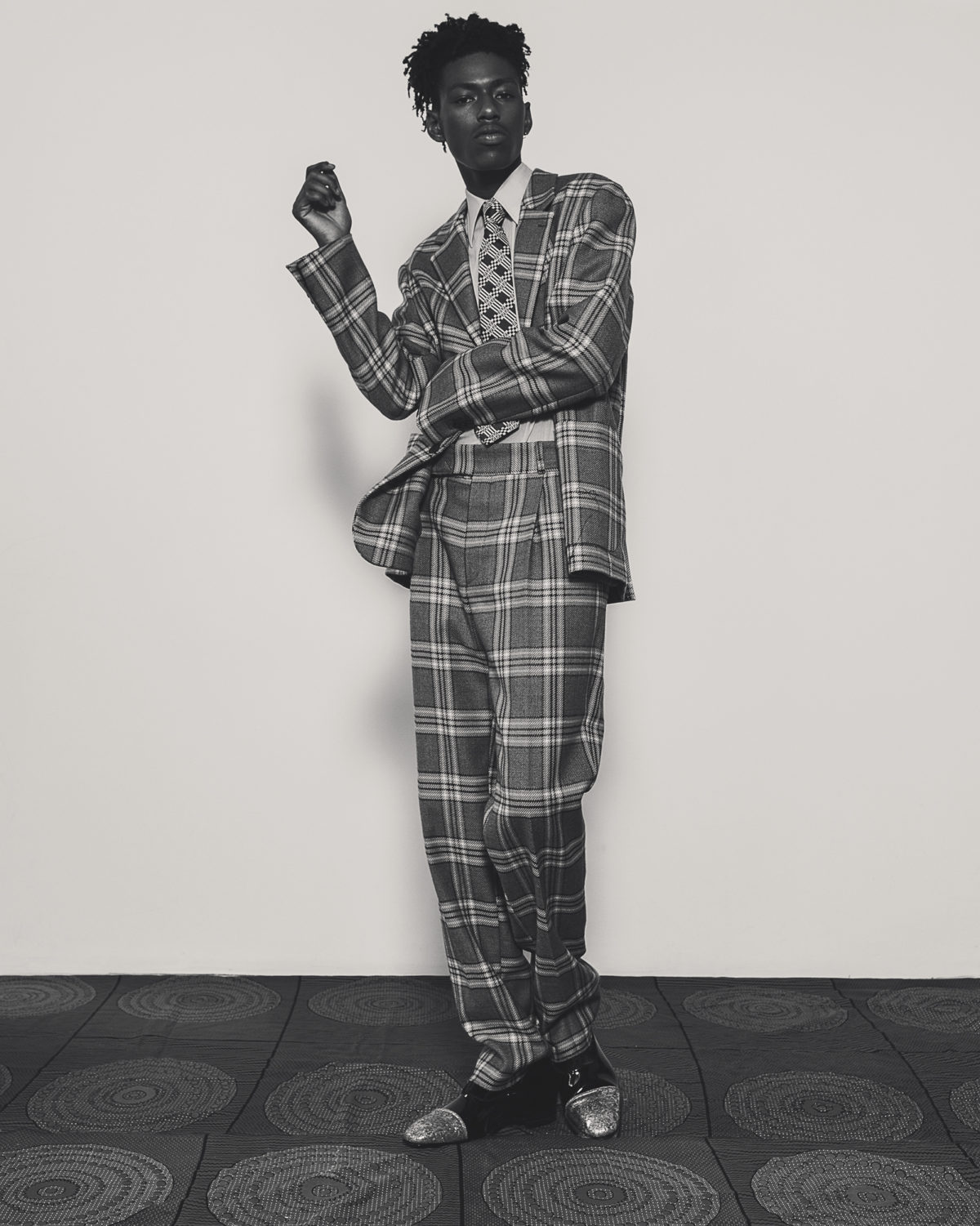

Ruth Ossai, London, 2017.

©RUTH OSSAI

Part of the intention of creating a set that is totally black, with black models and black photographers, is to get away from some those stereotypes that have produced marginalized expressions of racial identity—that have, for the better part of Western culture, equated blackness with ugliness. More and more, black artists don’t give a shit what white society thinks, and they’re no longer interested in playing by the rules. You have Jamal Nxedlana in South Africa thinking about post-apartheid image-making—thinking about how do you control images [and] legacies like Drum magazine, whose images are locked away because it was never really controlled by black photographers. You have Daniel Obasi thinking about Afrofuturism in Nigerian and pan-African contexts. You have Awol thinking about symbols in his still-life photography—symbols like Nefertiti that recur and have been whitewashed. You have black images that are meant to be consumed by black audiences.

As much as they show up in glitzy magazines, they’re also showing up in self-produced publications by these artists, like Campbell Addy, who has Niijournal. Then you have something like Beyoncé and Awol working together. They could have gone to any publication in the world to run Beyoncé’s pregnancy announcement and images, but they chose her website and her Instagram—platforms that they had more control over. It’s not that different from Awol curating exhibitions on Instagram or using his Tumblr as a look into his studio.

It’s seizing the means of production.

Exactly. That’s the only way these photographers got into the mainstream. There’s this misconception that these different mainstream institutional players somehow woke up. No—these black artists have been doing the work and, through doing the work, they were largely rendering these institutions irrelevant. That’s why I wanted to make this book, to make sure that people knew that. As much as there are legitimate questions about deemphasizing whiteness and the white gaze, one strategy that has emerged is not engaging that conversation at all. This is a criticism of the art world. Often, if you’re a black artist, you have to engage whiteness for your shit to be shown at the Whitney or any of these institutions, as opposed to creating totally black worlds.

Awol Erizku, Untitled (Forces of Nature #1), 2014.

©AWOL ERIZKU

Many photographers in the book are thinking about the Kamoinge Workshop, Seydou Keïta, and Malick Sidibé, and others more than white photographers like Annie Leibovitz, Inez & Vinoodh, and Collier Schorr. Is this part of crafting a self-sustaining ecosystem?

It’s also a part of this history and lineage of photography. You only get official portraiture of black people with the advent of photography, so you can go back and reference the history because it exists. All the major black portraitists that emerged over the last 50 years are deeply beholden to photographs: Amy Sherald, Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, Barkley Hendricks—the paintings that are deeply resonating right now. Jordan Casteel, by and large, draws on photography. I was just in Philadelphia and saw Jonathan Lyndon Chase—photography!

Artists are starting to create archives of black photography, like Theaster Gates, whose Black Image Corporation collects pictures from Ebony and Jet as well as vernacular pictures. Is that part of the same dynamic?

There’s such a construction of identity in those images that helps you think about photographs or how you want to pose in them. Fashion and vernacular photography have a more direct impact on our culture than any other kind of photography. They literally have told us what’s beautiful and what’s not.

Micaiah Carter, Sheani, 2018.

©MICAIAH CARTER

Many of the artists in your book are dealing with gender and sexuality, but never in a way where it’s in relation to historical notions of whiteness and masculinity.

It’s intersectionality. With respect to gender and sexuality, blackness has evolved. You have Micaiah Carter, who does traditional black-and-white photography that speaks not only to African-American studio portraiture—James VanDerZee, etc.—but also Africa. You have those fusions. Those two strands of black portraiture are never put into conversation in a significant way. We know African studio portraits, but we don’t think about what James VanDerZee was doing, what Charles “Teenie” Harris was doing. They were never allowed into the fashion pages. And if James VanDerZee is not, in part, a fashion photographer, I don’t know what a fashion photographer is.

Part of [writing the book] was trying to recontextualize some of the art history, too—trying to say, “Yes, these images exist in art-historical contexts because of the work by people like Deb Willis, bell hooks, Thelma Golden, Sarah Lewis, Skip Gates, a lineage of black curators and thinkers who have placed them there.” But they also belong to other contexts, namely fashion. When James VanDerZee captured someone, they were dolled up. He manipulated those early prints to heighten to the sensuality and the sitter’s identity. And by the way, he has a famous image of a trans person, so he was also thinking about gender, the ways in which identities were expressed outside tradition. My job was to connect things, to say, “Hey guys, this is new and necessary and great, but it also exists in history.”

Adrienne Raquel, In My Bag, New York, 2018.

©ADRIENNE RAQUEL

Whereas fashion photography may have once been stigmatized, this no longer seems to be the case. Do you think the boundaries are starting to blur?

For sure. Art photographers now want into the fashion game. Mickalene Thomas, it’s so natural for her. Carrie Mae Weems. Lorna Simpson, who doesn’t consider herself a photographer. Deana Lawson, who separates commercial work and art work. I think there are some limitations in art, meaning there’s an audience limitation. Shit is overwhelmingly white. The people who buy and consume it—they’re white, mostly! If you want to make sure that it is getting out into the world, one way you can do that is through commercial fashion images. If you think about it, it’s subversive, really. It’s less about wanting to move into the fashion-image space than taking it back, or using the fashion image to express desires that you would express in another space. The Carrie Mae Weems cover of Mary J. Blige for W? That’s a work of art.

[ad_2]

Source link