[ad_1]

According to Birx, that breakthrough is antigen testing. Often used to check for the flu and strep, antigen tests look for pieces of a virus — often the proteins that cover its surface.

That differs from most coronavirus tests, which look for the virus’ genetic material and require a number of chemicals to run, many of which are in short supply. The tests can also take hours to run.

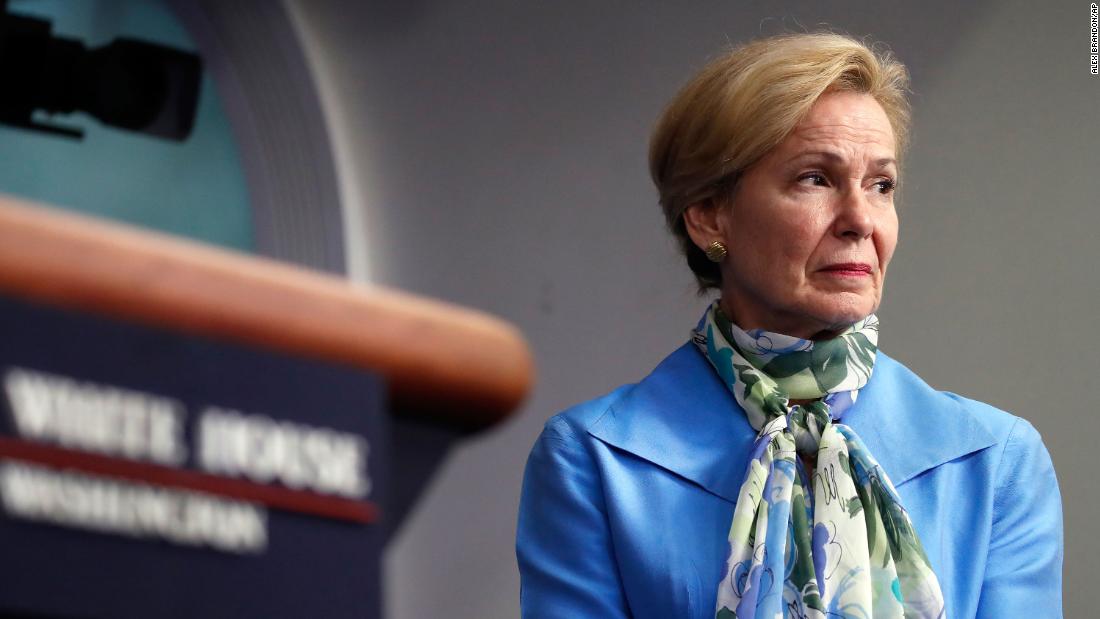

“There will never be the ability on a nucleic acid test to do 300 million tests a day or to test everybody before they go to work or to school,” Birx said earlier this month. “But there might be with the antigen test.”

With a potential market of hundreds of millions of tests a day, why doesn’t the US already have multiple tests?

For starters, the tests are not easy to make, and validating their accuracy can be time-consuming and expensive. For another, there hasn’t been a big market for them before now.

The first tests for the coronavirus looked for specific genetic sequences, which were identified within weeks. Once those sequences were selected, tests could be made quickly — barring manufacturing issues and supply chain shortages.

But antigen tests are tailored to the 3D structure of the targeted virus, which is more nebulous than a neat, orderly genetic code. Making a test that comes back positive for the novel coronavirus — and negative for everything else — is hard.

The tests look for hallmarks of the virus

An antigen is anything the body’s immune system can recognize and respond to, and any foreign substance can be an antigen. When our bodies make antibodies — proteins that defend against intruders — those antibodies are targeted toward antigens.

Every human face has characteristic features, like the shape of someone’s cheekbones. And every virus, too, has unique properties. And just as iPhones can remember a face, the immune system can remember different microbes.

Antigen tests, when they work properly, do the same thing — they recognize the structures that characterize different viruses or bacteria. But designing the tests can be challenging, according to Gigi Gronvall, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

The tests essentially try to trap antigens — structures on the surface of the virus — but they have to be carefully tuned. “Sometimes viruses may have special folds, or protein modifications on their surface, which can interfere with the process,” said Gronvall.

“And then, on top of the design part, you need to have enough of the virus in you to test positive,” she added. Tests that look for RNA, the virus’ genetic material, copy it over and over again. That amplification takes time — slowing down the testing process — but it allows for small amounts of virus to be detected.

Antigen tests, on the other hand, are often self-contained. They’re small, like pregnancy tests, and they can’t amplify the virus. “Genetic material is a universal language,” which allows it to be easily copied, Gronvall said. “It’s not as complicated as when a virus is all put together and ready to infect.”

World Health Organization cautions against antigen tests until more is known

The tests, according to WHO, are fairly simple, beginning with a sample taken from a patient’s respiratory tract.

“If the target antigen is present in sufficient concentrations in the sample, it will bind to specific antibodies fixed to a paper strip enclosed in a plastic casing, and generate a visually detectable signal, typically within 30 minutes,” the agency says.

But the tests come with risks. Their sensitivity — the ability to correctly identify patients with Covid-19 — ranges from 34% to 80%, according to WHO.

“Based on this information, half or more of COVID-19 infected patients might be missed by such tests, depending on the group of patients tested,” the agency says.

And false positives can occur, too. The test strip, for example, might recognize other human coronaviruses, like those that cause the common cold.

But tests that overcome these challenges, according to WHO, “could potentially be used as triage tests to rapidly identify patients who are very likely to have COVID-19, reducing or eliminating the need for expensive molecular confirmatory testing.”

A federal agency is funding antigen test development

Birx isn’t the only government official interested in antigen testing. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), part of the US Department of Health and Human Services, awarded $710,000 to a test manufacturer earlier this month to accelerate a coronavirus antigen test.

The company, OraSure, had previously developed a rapid antigen test for Ebola, which was green-lit by the Food and Drug Administration last year. In announcing the new funding, BARDA said the company’s coronavirus test would “allow people to be screened and triaged within minutes rather than waiting several days for test results.”

OraSure’s CEO, Stephen Tang, told CNN that he hoped to have a test available by September. The test would use saliva, like an HIV test made by the company. OraSure said it was hoping to ship millions of coronavirus tests within months of development.

While antigen tests for the flu and strep are imperfect, they’re widely used given their simplicity. It remains unclear, though, whether that model could work for the novel coronavirus, given how challenging it is to make a test and how important it is to have accurate results.

“I’m not discounting the fact that there are significant technical hurdles and we need to satisfy all of those issues,” said Tang. “I’m just saying that we have experience doing so.”

While he said some results may need to be confirmed through other methods — like traditional PCR tests — Tang framed antigen tests as the most practical way to dramatically scale up coronavirus testing and, eventually, the return to normal life.

“Because there is no treatment that’s been yet defined, and there’s certainly no vaccine, the best that we can do as a society is make sure that those who are infectious stay away from people that aren’t,” Tang said. He added that the company is looking at ways to eventually make hundreds of millions of tests.

Another company, Nanomix, received half a million dollars to develop a test that could also detect antigens. BARDA is funding 16 tests, a spokeswoman for HHS told CNN, including some antibody tests that could detect prior infections.

Nine of the BARDA-supported tests, she said, have already received emergency-use authorizations from the FDA, although none of those have been antigen tests.

[ad_2]

Source link