[ad_1]

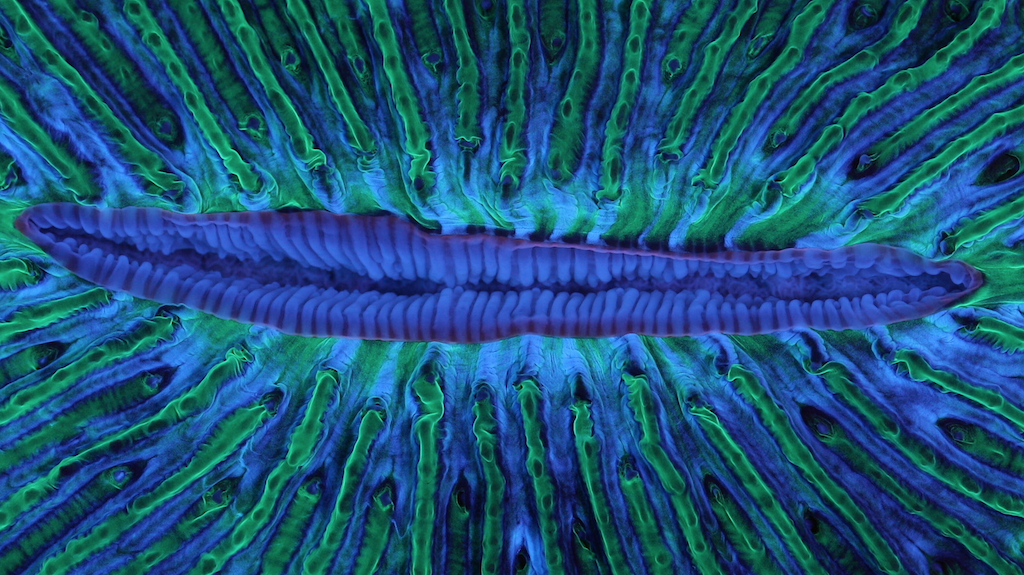

Still from Tangerine Reef by Animal Collective and Coral Morphologic.

COURTESY THE ARTISTS

Tangerine Reef, a new audiovisual album by the musical experimentalists in Animal Collective, evolved out of Coral Orgy, a collaborative performance for which the art-science videography duo Coral Morphologic projected otherworldly imagery of small-scale sea creatures across five screens while the band played new music in response. After the event, at the Borscht Film Festival in Miami in 2017, the musicians retreated to a Baltimore studio to record a definitive version of their set, while Coral Morphologic went home to film all new footage for a final cut of what would be their highest-profile project yet.

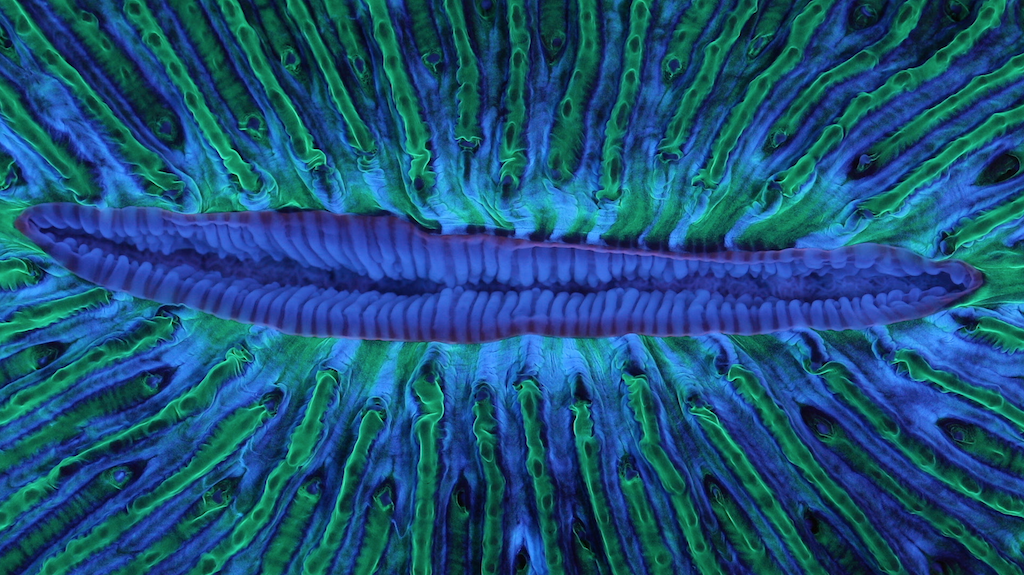

Animal Collective might be familiar after nearly two decades of burbling up from the art-minded rock and electronic music underground, but Coral Morphologic works in a more arcane realm. Founded in 2007 by marine biologist Colin Foord and musician J.D. McKay, the duo creates self-described “avant-garde coral macro-videography” by shooting footage in their laboratory in an unassuming house on a residential street in Miami. In a setting that could more easily be a dining room, there is now a living archive of coral species in large water tanks bathed in glowing blue LED light. The cool illumination allows the corals to reveal their natural fluorescence in an otherwise unnatural locale.

The house where Coral Morphologic’s magic happens.

COURTESY CORAL MORPHOLOGIC

“ ‘Tangerine Reef’ is not an actual place,” Foord explained, “but rather a community of creatures from around the globe that we brought together in our lab to record in a more patient manner than could be done in the wild. We’ve been propagating many of the corals for years. They start out as small one-centimeter fragments grown by other aquaculturists in the U.S. or a nursery in Indonesia, where they are sustainably farmed.”

As caretakers and scientists, Coral Morphologic have conducted extensive fieldwork to document the unique nature of Miami’s coral systems. Over the years they have discovered four zoanthid “soft coral” species, and together they have received grants from the National Ocean and Atmospheric Association (NOAA). “My academic background is that of a scientist who turned to art after deciding it was a better medium to convey environmental issues to the public,” Foord said of the duo he created with McKay, who has a background in music and English. “We hope that Coral Morphologic can illuminate a new path where art and science are blended to create personal connections between humans and other life forms.”

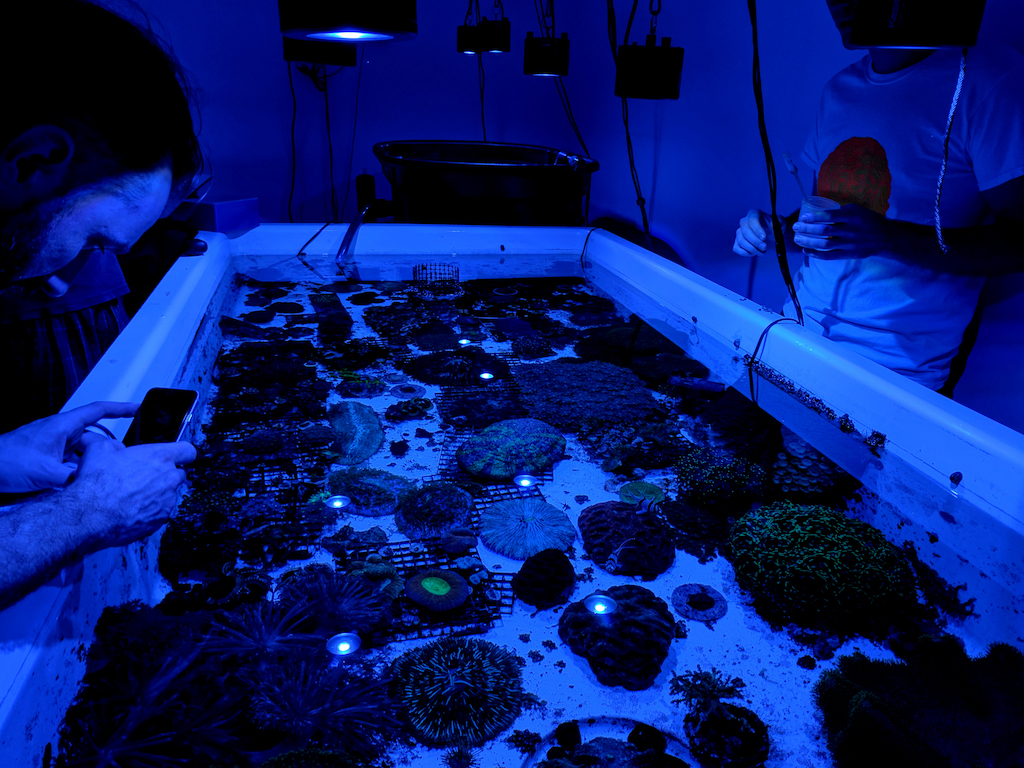

Coral Morphologic forged a friendship with Animal Collective—especially the band members known as Deakin and Geologist—through a mutual love of scuba diving and ecological awareness. When they travelled together to Turks and Caicos for a dive trip in 2011, their bond was strengthened as they rode out Hurricane Irene in a hotel. In 2014, they descended into the deep again off the coast of Texas. “The trip we did to the Flower Garden Banks was amazing, especially the night dives,” said Deakin, also known as Josh Dibb. “When you’re diving there’s a blue LED light that adjusts to night, and you put this yellow filter over your mask. It was a magical experience, to be underwater and see that kind of imagery. The stuff in Tangerine Reef has that same kind of effect.”

Coral Morphologic at work.

COURTESY CORAL MORPHOLOGIC

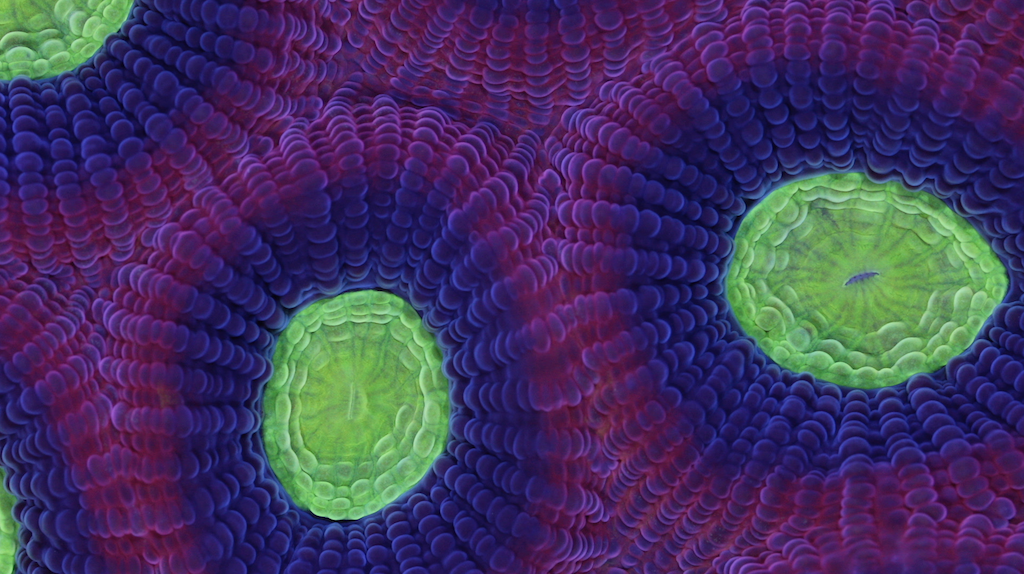

Tangerine Reef’s extreme saturation and detail are at once astounding and unsettling. Shots include lush abstracted corals in shallow focus against dark backgrounds, like black-velvet paintings from the sea. A monochrome array of fern-like creatures transitions into a speckled neon field, some of nature’s own new-wave design. Another entity that looks like an underwater Venus flytrap has undulating edges that pulsate red and blue in what appears to be some trick of entrapment. The goals of certain biological processes at play upon the screen are obvious, as when a feasting sea cucumber reaches its net-like tentacles out to catch plankton. Other processes turn out to be exactly what you hope they would not be (see: an ejaculating sea anemone).

On the decision to approach Tangerine Reef as an audiovisual album, Foord said, “We’ve tried to make an experience where the audio and the visual elements work together synergistically, like 1+1=3. It is a kind of tone-poem similar to 1982’s Koyaanisqatsi scored by Philip Glass.” Another source of inspiration is Jean Painlevé, a prolific filmmaker whose work with underwater and scientific subjects from the 1920s to the 1980s led to a Criterion Collection release of his work, Science is Fiction, that included a posthumous selection of films scored by the band Yo La Tengo. “The works of Painlevé are really seminal for us,” said Foord. “He was doing a very similar hybridization of art, science, education, and pop culture in an aquarium studio almost a century ago.”

Left to right, Animal Collective’s Avey Tare, Tangerine Reef director John McSwain, Deakin, J.D. McKay, Geologist, Colin Foord.

GESI SCHILLING

Working in tandem with the visuals, Animal Collective’s musical palette mimics a descent into underwater realms with slack, swirling guitars and echoing synthesizers that rise and fall in resonance. The first sounds in the recording are distinctive clicks and woody pops. “Those sounds are mimicking the sound of coral,” Deakin said. “Reefs are really loud. When you’re down there, the breathing apparatus for scuba gear is also loud. If you listen between breaths, or if you’re far enough away from other divers, you’re aware of this constant ‘popcorn’ crackling going on.”

Watchers of Tangerine Reef peer into a world that does not pretend to concern itself with human form or focus. In a sort of alienating descent (putting aside any phobias of space, infinity, and the deep), observers are asked to think about what is below and beyond, to intersect with spaces at scales that are not our own and in the service of multiplicities of time, motion, and location. One might expect lots of time-lapse treatment, but when the slower movements of the corals are sped up, it is only to accentuate certain processes. “By speeding up the corals’ timescale to one that humans can perceive,” Foord explained, “we hope that people are able to empathize with them—and, even better, to learn a thing or two about living and symbiosis with neighbors.”

The majority of the film provides macro-scale views of one type of reef-dwelling species at a time, turning the lens toward the minute behaviors and unseen liveliness of non-human species who, as the credits roll, are given credit as actors and collaborators. “The most common question we get about corals and reefs is: Why are they important to humans?” said Foord. “This type of thinking presupposes that a life form is only worth saving if it protects our real estate or offers a cure for cancer. Corals don’t need to justify their existence for anyone’s convenience or protection.”

In the process of entanglement between human and non-human forces, viewers are forced to reckon with our collective reciprocal relationship with these creatures—our ability to help them and to harm—while the corals either adapt or become extinct in the face of climate change. “When you get in the water, you see the reality of how complex the ocean systems are—how incredible the mechanism of the planet is and how crucial those environments are to our lives,” Deakin said. “I hope that’s what comes out of the film for people.”

Still from Tangerine Reef.

COURTESY THE ARTISTS

All parties involved are fans of Charles and Ray Eames’s 1977 film Powers of Ten, which visualizes the scale of the universe through exponential camera pans and zooms—from a picnic in Chicago out to the edges of space and back again into the cells of a body lounging on a blanket in the Windy City. “What a great film,” said Foord. “It is our intent to make films that resonate from the scale of the microscope to that of a telescope. From our perspective, we see corals as the first astronomers and timekeepers of planet Earth. If we pay attention to them, corals can help elevate human thinking towards the logarithmic scale that Powers of 10 demonstrates.”

In its last half-hour, Tangerine Reef takes a turn toward cosmic noise as the audio and visual effects begin to lock in together especially well. Poignant-seeming voids, geographies, and coral-made mandalas become worlds that collapse inward and expand as the camera retreats. “To be able to present archetypal organisms with a mythos to convey,” Foord said, “is an opportunity we don’t take for granted.”

[ad_2]

Source link