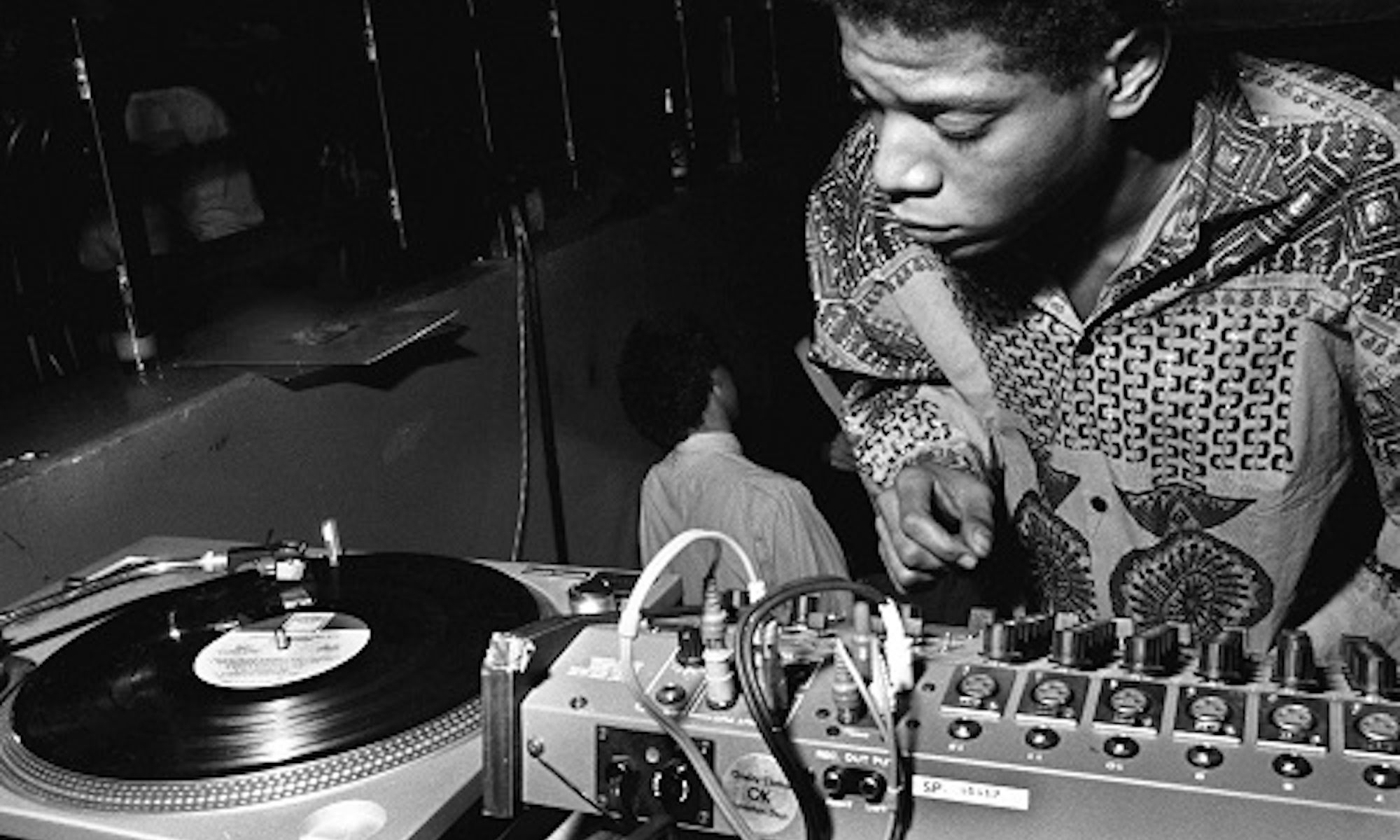

Basquiat DJing for Eric Goode’s birthday party at Area, 1984. Photo Ben Buchanan. © Ben Buchanan

Thirty-five years after Jean-Michel Basquiat’s death at age 27, he is perhaps more famous than ever before. Much of that fame is derived from his market, his tragic biography and the assimilation of both into globalised pop culture. From the $110m that Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa paid for his skull painting Untitled (1982) and the Broadway show about his friendship with Andy Warhol, to the prolific licensing of his art for merchandising and the rapper Jay-Z name-dropping him (and collecting his work), Basquiat is everywhere.

But as Basquiat’s prices and life story have taken centre stage, actual engagement with his rich and densely referential oeuvre has often been sidelined in exhibitions—a 2019 exhibition at the Brant Foundation in Manhattan, for instance, gathered seemingly every major Basquiat in private hands and displayed them with virtually no context or information. This is unfortunate, as his work has only become more urgent and incisive with time. Seeing Loud: Basquiat in Music (until 19 February) at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts is a welcome corrective to this tendency, delving into the myriad ways that music shaped the artist’s work. (Following its run in Montreal, the exhibition travels to the Philharmonie de Paris.)

Co-organised by the museum’s chief curator, Mary-Dailey Desmarais, and guest curators Vincent Bessières and Dieter Buchhart, the show brings together an incredible breadth of archival materials, drawings, paintings, journals, recordings, installations and more to make a convincing argument: that music is crucial to understanding Basquiat’s work, first for how he was nurtured by and emerged from New York’s Downtown music scene at the turn of the 1980s, and then in the ways that the formal features of jazz, hip-hop and other genres influenced his painting practice.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, King Zulu, 1986. MACBA Collection, Barcelona, Government of Catalonia long-term loan (formerly Salvador Riera Collection). © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Looking at Basquiat’s work through a musical lens is not an entirely novel idea—many of his paintings make the connection unmissable by referencing and depicting musical terms and icons. But given that fact and the global, year-round circuit of Basquiat exhibitions, it is shocking that this is the first museum show devoted specifically to the topic of music in his oeuvre.

“Once you really start to look at those paintings, you understand all the layers of meaning that were embedded in them and how deeply they are connected to music,” says Desmarais. “One of the things that goes hand in hand with that is understanding the spirit of the time in which he was working, the cross-pollination between music, visual arts and poetry. Music is how he started his career—he’s making flyers for musicians, he’s earning his living through his engagement with music—and we really wanted people from the beginning of the show to be immersed in that time.”

The exhibition opens by plugging visitors into the New York music scene of the late 1970s and early ’80s via a collection of ephemera. It is installed in dimly lit galleries divided by walls with exposed beams, a design flourish intended to evoke the architecture of the Lower Manhattan lofts where much of the era’s paradigm-shifting art and music were being made and shown. Basquiat’s work here—recordings of experimental, noise-heavy No Wave musical performances, the posters he created to promote them, snapshots and sketches of friends and acquaintances, photographic and collaged collaborations, and more—illustrates the creative fluidity of the time Anyone and everyone in the scene, seemingly, was making art, writing poetry, shooting films and photos, performing with a band and more, sometimes all in one night. And no one was a more ravenous, prolific polymath than Basquiat.

View of the exhibition Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo MMFA, Denis Farley

“Communicating with people in any way was important to him,” Anna Domino, a friend and musician who was part of the Downtown scene during the brief lifespan of Basquiat’s experimental band, Gray, says in an interview with Bessières for the exhibition catalogue. “I think he was trying everything, any medium or process where a connection could be made.

“But he decided that the music business was even worse than the art world—more difficult, more thankless, harder to make a dent in, get paid or find your voice in, because you had to work with other people,” she adds. “He wanted just to focus on what was coming directly from the stars onto the canvas.”

One of the highlights in the exhibition’s narrative of Basquiat’s evolution from ubiquitous No Wave scenester to singular visual artist is a gallery featuring a re-creation, by artist Peter Artin, of an improvised musical instrument he built for a Gray concert at art dealer Leo Castelli’s birthday party in 1980. A salvaged shopping cart fitted with various bits of scrap metal and an electric motor, it clangs thunderously, evoking an earlier era of avant-garde assemblage. (Desmarais, in her catalogue contributions, makes a compelling case for thinking of Basquiat’s work as descended from Dada.)

View of the exhibition Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo MMFA, Denis Farley

In the next gallery, the exhibition’s parade of huge, knockout paintings begins. It includes Anthony Clark (1985), a large portrait of graffiti artist A-One executed on wood planks and incorporating collaged photocopies of Basquiat’s sketches. It echoes the previous room’s shopping-cart instrument in its use of found materials and assemblage, but it also demonstrates how Basquiat adapted his love of music into visual form, most notably in the way his reproduction of his own drawings evokes the musical sampling of hip-hop. The fragments of text also mimic the improvisational scatting of jazz singers as well as rappers’ freestyling—the latter audible in the gallery thanks to documentary footage of early hip-hop performances playing nearby.

“He was much more than an artist who liked to paint while listening to music—which he did,” says Desmarais. “He was thinking about all of the ways that music, poetry and imagery resonated.”

Basquiat’s evolving deployment of language is one of the exhibition’s most prominent motifs. It tracks his use of text from the SAMO© tags and poems he and fellow artist Al Diaz started writing on the streets of Manhattan in 1978 to his prolific notebook entries, which in turn informed (or sometimes, via photocopies, became) parts of paintings. As Greg Tate wrote in his essential 1989 essay “Jean-Michel Basquiat, Flyboy in the Buttermilk,”: “Truly, many of his paintings not only aspire to the condition of poetry, but invite us to experience them as broken-down bluesy and neo-hoodoofied Symbolist poems.”

One gallery is covered entirely in pages from Basquiat’s notebooks, which demonstrate his knack for poetic composition as well as his musical uses of text. “They show that he understood the sound and shape of words and the musicality of language,” says Desmarais. They also underscore his graphic use of text, with words repeated, rearranged and crossed out for emphasis and dramatic effect.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, A Panel of Experts, 1982. MMFA, gift of Ira Young. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo Douglas M. Parker

“I cross out words so that you will see them more,” Basquiat once told the art historian Robert Farris Thompson in an interview quoted in the catalogue for the Whitney Museum’s posthumous Basquiat retrospective of 1992. “The fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them.” This is demonstrated most devastatingly in Slave Auction (1982), which depicts the sale of enslaved Africans and draws parallels between the use of slave labour and the exploitation of Black athletes and musicians in the 20th century. Along the bottom of the canvas, the large and partially crossed out letters “PRKR” allude to one of Basquiat’s heroes, jazz legend Charlie Parker.

Across the exhibition’s galleries, many of which are filled with musical recordings relevant to the works on the walls, the paintings’ texts and musical allusions—from Parker, Fats Waller and Dizzy Gillespie to Beethoven and Madonna, with whom Basquiat had a brief relationship—begin to coalesce into a kind of soundtrack of their own. Some works evoke a bright and catchy sound, like his loud collaboration with Warhol. Others are lyrical and dense with samples, like a rap song. Some are loquacious yet enigmatic, like a free jazz performance. One comes away with a sense that, even though he decided to make his mark in the art world rather than the music business, the power of Basquiat’s work derives in part from how he was able to re-create music’s visceral force on canvas.