[ad_1]

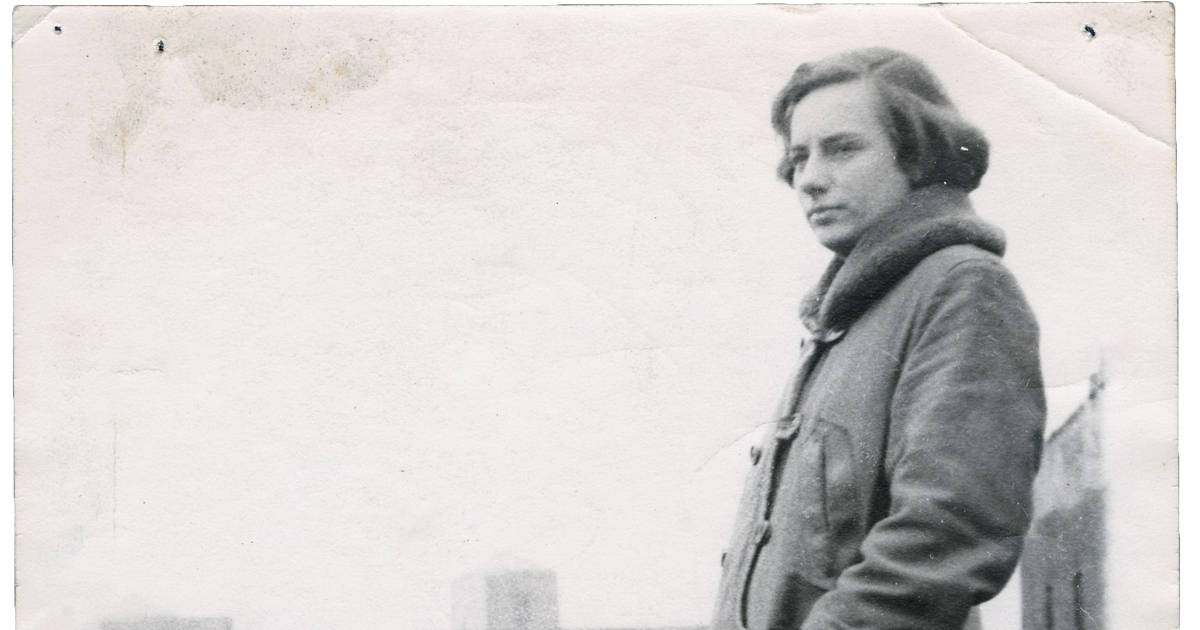

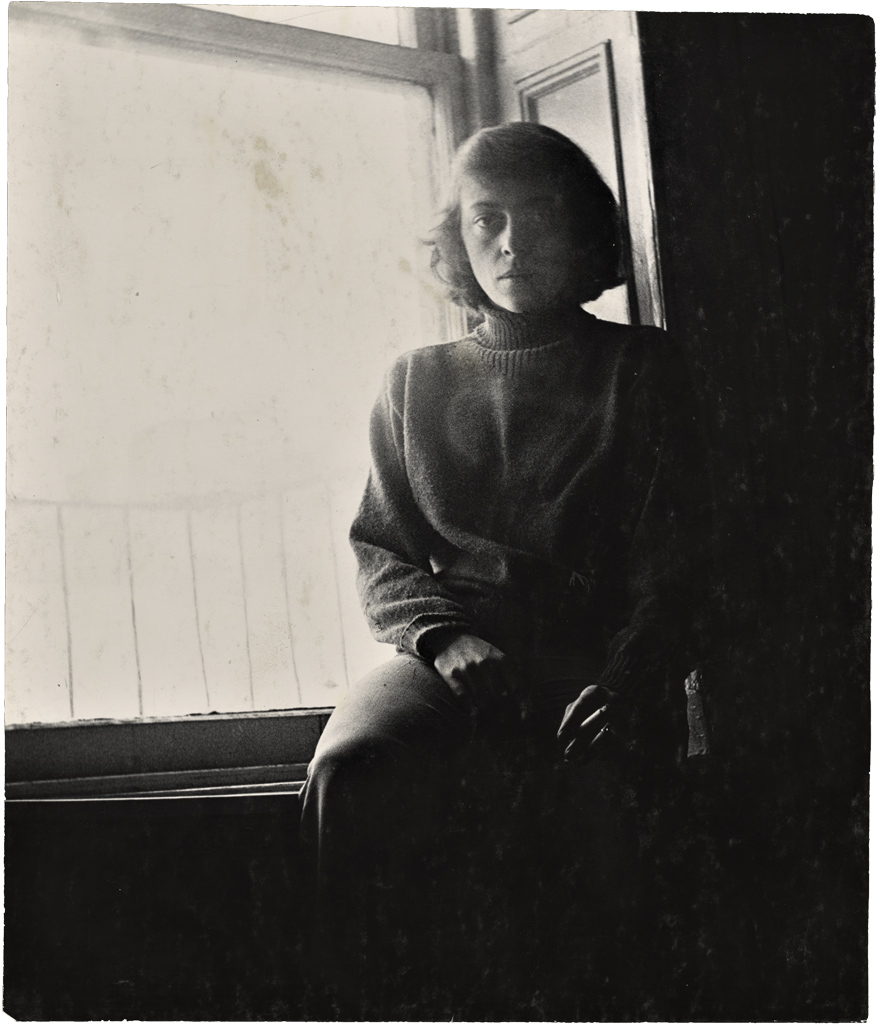

Grace Hartigan on the roof of the studio she shared with Al Leslie, ca. 1951.

COURTESY HACHETTE BOOK GROUP

On October 9, 1954, Grace [Hartigan] discovered her River Bathers hanging in the Museum of Modern Art as part of an exhibition, “unprecedented” in scope, of 400 works by major artists.1 Paintings from the Museum Collection inaugurated a year of celebration marking the twenty-five years since “the ladies” and Alfred Barr had opened their improbable museum.2 Upon learning that the show had been hung, Grace rushed to the museum and into the galleries housing the newly minted American greats—Gorky, Bill de Kooning, Pollock among them. It was within that constellation of talent that Grace found her work, and she felt, as she looked at it, that this was where she belonged. “It is a beautiful picture,” she confided to her journal the next day. “I am proud that Barr feels what I know myself, that I am the equal—and more—of most of my American contemporaries.”3

With an uncharacteristic acknowledgment of her sex, Grace continued,

I regret sometimes that this great gift has been born to me, a woman, with the countless flaws of vulnerability, worldliness, fears—what all! I have. . . . So be it, I try to live the life that is necessary for it to flow. If fame is to come to me, it will require great strength to continue to work and keep the proper distance, the correct understanding in regard to my inner or spiritual self and my outer or worldly one.4

From the time she had sat enchanted as a child watching Hollywood stars in the movies, Grace had anticipated fame. Seeing her painting in the Modern—and at one point watching a father with his child stand before it and explain the figures she had painted—filled her with pride over what she had accomplished on canvas and who she had become in life.5 Grace had crossed the threshold. She was now the person she once dreamed of.

Indeed, among her generation of artists, Grace occupied an exalted position in terms of recognition and commercial success. No one else had sold out a show or had works in two of the three New York museums that featured modern art. Even compared with most First Generation painters, Grace was doing quite well. Using sales as a barometer of success, Grace had sold $5,500 worth of work in 1954, just short of Bill de Kooning’s $7,000 during that same period.6

Her ascent was remarkable, and it did not go unnoticed. Her phone began to ring with interview requests, Newsweek and Glamour among them. “For the last few days I have been working on this painting with one hand, and trying with the other to keep my door closed against the outer world—phone calls!” she wrote in November.8 Within the span of a few weeks, in addition to a group show at Tibor de Nagy, she had been asked to send five paintings to an exhibition in Minnesota, another to the Whitney for its important annual exhibition, and fourteen more to Vassar. The college wanted to mount a solo show of “Grace George Hartigan’s” work.9

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY, NEW YORK

The attention had come Grace’s way because of her talent but also because she was a fascinating phenomenon, one that embodied a previously nearly unimaginable combination: a successful, young, independent American woman and artist. (Omitted from that portrait was how she had achieved that state: by eliminating all entanglements from her life, including her son.) Just as Pollock (minus the alcoholic psychosis) represented a new breed of American man, the sanitized-for-public-consumption version of Grace exemplified a new breed of woman. Strong and self-made, she was free of both the inaccessible gentility and the incomprehensible eccentricity many had come to expect from the rare woman who dedicated her life to paint or stone. As Jackson had looked like everyman, thereby proving that social pedigree was not an essential ingredient in making art, Grace personified a liberated version of everywoman. She even spoke with a New Jersey accent!

When Grace addressed a Vassar gathering during her show, she inspired her audience from the moment she crossed the stage. One student recalled being struck by her confident stride. Another by her ease at the podium: She spoke conversationally, peppering her comments with language that would have been unremarkable at the Cedar Bar but shocking at a Seven Sisters assembly.10 “I was just dazzled,” said future art historian Linda Nochlin, who heard Grace as a student, “because you know we all wore skirts and she came up in her paint-covered blue jeans and smoked all during her talk. And she was just marvelous. I mean she was a true artist.” For Nochlin, a “light went on.” Grace was proof that a woman “could do everything, anything.”11

Grace’s celebrity occurred at the dawn of a “gold rush” in the New York art market. The United States was now a full-fledged consumer economy (the credit card had been born), with business and consumer confidence indexes stable.12 In addition to that salubrious environment, the U.S. tax code had been changed to allow art collectors to take a deduction on art purchased with the intention of donating the work to a museum.13 That bureaucratic change had two immediate effects for the buyer: Wealthy individuals had an incentive, beyond a love of art or the acquisition of the ultimate status symbol, to buy paintings and sculpture. And they were more focused in their pursuit, increasingly purchasing works on the advice of a small number of “experts” who directed them toward art most likely to be accepted by a museum.

For the nation’s more than 2,000 museums, the change produced a bounty in promised donations of works.14 For galleries, what had been a few sales to a small pool of collectors became a relative flood. In 1955 “the scene opened up suddenly. Detroit and Texas money began feeling that this was a prestige item,” said gallery director Nathan Halper.15 And for artists? Even the New York School painters reaped the benefits. Paintings by Europeans cost a fortune: A Vermeer sold in 1955 for $350,000; a Matisse might be purchased for $75,000.16 But a Pollock or a de Kooning could be had for a relatively paltry sum, and some people hoping to get in on the art market saw the Abstract Expressionists as a more affordable pathway.

Fortune would publish a lengthy feature that year advising readers on art as investment. Describing a Vermeer as that 17th-century Flemish master’s work had never been described, the magazine called it “one of the world’s most highly valued surfaces . . . at $1,252 per square inch” and compared its worth with that of the land under the House of Morgan on Wall Street, which was valued at just over $2 per square inch. Art, the magazine concluded, “can be the most lucrative investment in the world.”17

Its readers were told that the market could be divided into various categories based on style, history, and quality, of course, but also on price. There were the “Old Masters,” a limited pool of works by long-dead artists, which for those with pockets deep enough to purchase one, were an investment “as good as gold.”18 Next were “blue-chip” paintings and sculpture—a category Fortune defined as “you can’t possibly lose.” These included 19th- and 20th-century Europeans: Monet, Manet, Matisse, Picasso, and Gauguin.19 Finally, the article described the “speculative” or “growth” market, which could include work by new artists. Near the bottom of Fortune’s list appeared the names de Kooning, Motherwell, Pollock, Rothko, Kline, and Rivers. Their prices ranged from only a few hundred dollars to several thousand. Though the risk to investors was high, the potential reward for the “shrewd and lucky” speculator could be enormous.20 Some among America’s postwar nouveau riche heeded that advice and took a chance on the new art. In 1955 Pollock sold his painting Blue Poles to a collector for $6,000. “The gossip spread like a forest fire,” Helen [Frankenthaler] said, “from the beaches of the Springs to the art world and beyond that. Unbelievable news.”21

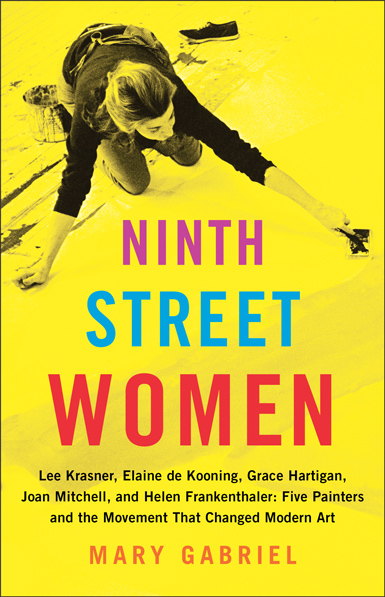

Helen Frankenthaler in front of Moutains and Sea (1952) at her West End Avenue apartment ca. 1954.

COURTESY HACHETTE BOOK GROUP

Gallery owner Sam Kootz said beginning that year it was “no particular struggle for any of the good men to exist because we sell enough of their pictures to have them make a very respectable income.”22 Notably absent, however, from either the Fortune list or Kootz’s comment was any mention of women—other than a reference to Georgia O’Keeffe. “The abstract movement made no distinction between men and women in judging the work itself so long as society ignored it,” explained author May Tabak Rosenberg. “But once accepted as respectable, then all the sexual prejudices of bourgeois society began to divide the art world.”23

And yet, at the start of the age when American art would be appreciated for its price as much as its quality, women were selling and showing. Grace was evidence of that. Her annual solo show at Tibor de Nagy in 1955 was acclaimed by critics and sold out. Poet James Merrill paid $2,000 for her Grand Street Brides, which he donated to the Whitney. Nelson Rockefeller bought her Peonies and Hydrangeas for the Modern. The Chicago Art Institute purchased her 1954 painting Masquerade.24 As for her fellow painters, Joan [Mitchell] and Helen would be invited along with Grace to exhibit in the important 1955 Whitney Annual.25 Joan, Elaine [de Kooning], and Helen were chosen in 1955 to show in the prestigious Carnegie International in Pittsburgh.26 In fact, Helen’s painting The Facade was purchased for the Carnegie Institute.27

What such recognition meant was that if a gallery director defied ingrained sexism, as did John Myers, Betty Parsons, and Eleanor Ward, and showed work by talented women, those artists had as much chance as talented men to become part of the national art dialogue, and be included in museum exhibitions and collections. Unfortunately, there were not enough daring dealers to make that possible, and so women remained largely off the commercial and museum radar. Grace, Helen, and Joan were the exceptions. “I used to refer to them as ‘The Grand Girls,’ Hartigan, Mitchell, Frankenthaler,” art historian Dore Ashton recalled, smiling at the admission that she had felt slightly intimidated by those painters. “But I never let them know it!” As for their elders, Elaine and Lee [Krasner], Dore said, “I was a little afraid of Elaine. She had aplomb. She was the queen. I didn’t really like Lee, but later I got to be much more tolerant of her. All of my Grand Girls were interesting people. There’s no question about it.”28

As the art world began to cleave into two camps—those who responded to art regardless of the artist’s gender and those who saw only men’s work as serious—Dore’s “girls” stood out. “Those women paved the way for me,” said Marisol of that group.29 They would pave the way for generations of artists. “In the 1950s, with the emergence of Grace, Joan, and Helen, it was a new ball game,” said art historian Irving Sandler, who knew them all well.

They opened it up for women, in part because they were stronger than any of the [Second Generation] men. . . . In order to be a woman on the scene, you either had to remove yourself as Helen did, she went uptown . . . or you had to be tough, you really had to be tough, and they didn’t come tougher than Joan or Grace. I once asked Grace, “Has any male artist ever told you, you paint as well as a man?” And she said, “Not twice”. . . . Also, you know Lee and Elaine were intellectually brilliant. They all were really smart, and you don’t mess with that.30

The women of the New York School put their foot in the door that was being closed against them, not as an act of feminist protest but because inside was where they belonged. It is interesting to note, however, that at the time those women established what art historian Eleanor Munro called their groundbreaking “working presence” among the artists in New York, the social sands were shifting once again regarding women generally.31 A faint chorus had even begun encouraging them to emerge from the confines of their homes.

Grace Hartigan, The Creeks, 1957.

COURTESY HACHETTE BOOK GROUP

By the mid-1950s, women who had long been schooled in subservience were given a new goal: they should also strive to be mediocre. Magazines, films, television serials, books, and even some university courses advised women, no matter how intelligent, to downplay their abilities.32 There was, however, one area of “liberation” for women as the 1950s approached its midpoint. The Kinsey report on female sexuality had been published in 1953 with as much fanfare as his report five years earlier on men. Women, the report concluded, engaged in all kinds of sex, a good deal of it pre- and extramarital.33 While there was some ambiguity as to whether women achieved orgasm or had sex because they enjoyed it (if they did and the goal was not pregnancy, their orgasm was called “malicious”), that very confusion made the findings more palatable to mid-century readers.34 As a Reader’s Digest article concluded, “ ‘What Every Husband Needs’ was, simply, good sex uncomplicated by the worry of satisfying his woman.”35

Betty Friedan, who, as a young housewife during that period witnessed firsthand the strangely one-sided sexual revolution (which she called a “counter-revolution”), wrote in her 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, that sex became “the only frontier open to women.”36 And yet, Friedan wrote, neither the man nor the woman in that society was particularly happy with the ubiquity of libidinous relationships. After reaching the saturation point in books, magazines, films, and in reality, such activity felt hollow. Sex had grown dull. “This sexual boredom is betrayed by the ever-growing size of the Hollywood starlet’s breasts, by the sudden emergence of the male phallus as an advertising ‘gimmick,’ ” Friedan wrote.37 For those college coeds who had decided to skip “Mate Selection” or “Adjustment to Marriage” classes, or those housewives grown tired of a steady diet of courtesan tips in magazines, intelligent women’s voices had begun to surface that questioned the status quo.38

Simone de Beauvoir and Margaret Mead had studied the cultural history of women and discovered that while Western society had advanced in nearly every measurable way, its treatment of women had not. Their books, Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, published in English in 1953, and Mead’s Male and Female of 1955, made for challenging reading. Mead’s anthropological research had taught her that gendered behavior was cultural, not biological, and therefore entirely subject to change.39 Beauvoir had said as much earlier, writing, “It is not nature that defines woman; it is she who defines herself.”40 Historically, however, that had not been possible in societies dominated by men, she wrote, except among “women who seek through artistic expression to transcend their given characteristics.”41 Beauvoir was speaking of women in the performing arts, but she acknowledged the strides women were attempting to make in literature and visual art. In those areas, she warned, the forces of tradition might be insurmountable unless a woman was prepared to reject her so-called limitations and risk potentially crippling social disapprobation. “The free woman is just being born; when she has won possession of herself perhaps Rimbaud’s prophecy will be fulfilled: ‘There shall be poets! . . . she, too, will be poet! Woman will find the unknown!’ ”42

In 1955 a 20-year-old French author named Françoise Sagan arrived in the States, a manifestation of Beauvoir’s social philosophy and Rimbaud’s words. Her book about a young woman’s affair with an older man, Bonjour Tristesse, had just been published in English and she was on a book tour. Sagan’s picture appeared everywhere, her escapades described in starstruck detail. “She seemed . . . to have taken possession of her fame with great aplomb, living it up the way young male writers were supposed to,” recalled author Joyce Johnson, who was 19 at the time. “She had a predilection for very fast driving in expensive sports cars. . . . There was something in her speed, her coolness, that seemed . . . totally new.”43 Sagan had made her leap to liberation seem easy. The women of the New York School knew otherwise.

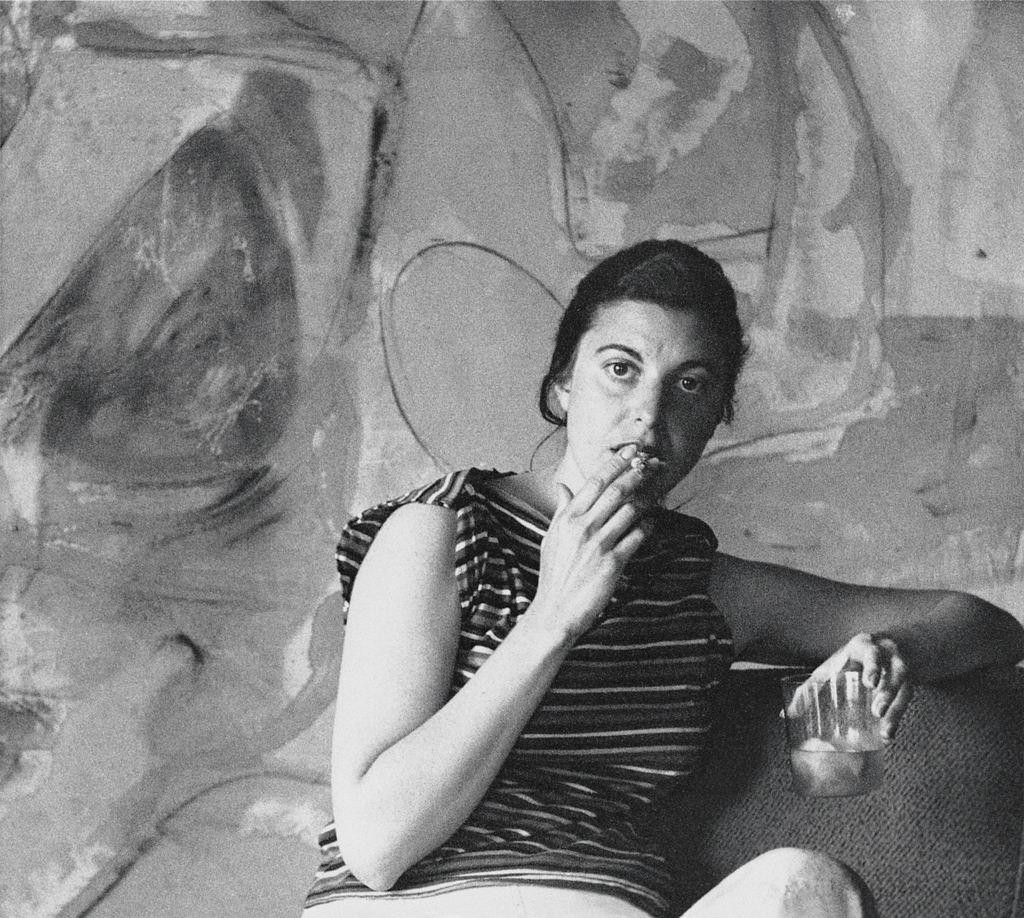

Joan Mitchell, ca. 1957.

COURTESY HACHETTE BOOK GROUP

During the third Stable Annual, young Marisol sold a sculpture and was so alarmed by the attention she received that she fled first to Mexico and then to Paris.44 Grace, too, was experiencing that disequilibrium. On her 33rd birthday, in March, she wrote, “Trying to think of a message for myself . . . but the only one that occurs to me is ‘courage!’ ”45 The nearer she approached the paintings she felt were truly her own, the more she sought isolation in the studio, and yet, isolation at that moment was impossible. Grace had discovered it was no longer just her work that was for sale. She, too, had become part of the transaction.46 Grace called the spring of 1955 “a terrible time for me, I am lost and floundering—and wors[t] of all, I can’t even flounder on a canvas, it is all in me, I can barely force myself to work.”47 Quite unexpectedly, an opportunity arose for Grace to escape New York, her studio, even herself, and she took it.

Painter Jane Freilicher and Joe Hazan had decided to marry, but before they could, Joe needed to divorce his wife, and he had chosen to do so in Mexico.48 By mid-May, poet John Ashbery, Grace, and Grace’s boyfriend, Walt Silver, had all signed on to the trip southwest in Joe’s convertible.49 “This motel is like a Hollywood B glamour film—I’m half in it and half laughing at it,” Grace wrote from Texas three days into the trip.50 After a week of heat and discomfort on the road, however, tempers began to flare. At the border, the group split up, with Walt following Grace reluctantly into the Mexican hills.51

“The first night we entertained every mosquito in Mexico,” Grace admitted. Despite her discomfort, she felt happy, absorbing the culture around her for use in her work. Even on vacation, Grace was preoccupied with painting.52 Like her son, Jeff, who had always felt second to art in her affections and attention, Walt felt a distant third, if not fourth in her life. During their Mexico trip, he decided he’d had enough, though Grace seemed too busy to notice.53 Back in New York in mid-June, she returned to her studio, free of the worry that had plagued her before she traveled, free of confusion about who she was.54 Until Walt announced he was leaving.

Stunned and admittedly afraid, Grace struggled with the possibility that she might never have a permanent relationship, and she questioned whether she needed or wanted one.55 For Grace, a lover was not an end but a means. Love, or lovemaking, was one more ingredient she needed and used to be in the right frame of mind to paint.56 Relationships were burdens she could not carry. “Until recently, women kept thinking that somehow they had to settle the man thing; somehow it was paramount,” Larry Rivers said, recalling that earlier time,

That wasn’t true for Grace, I think. She was just as interested in a career, in her work, and men were like dressing—a little bit of spice in life. She seemed to boss them around—like, “Don’t bother me, I’m doing my work, you can call between five and six.” That would seem very normal today.57

Said Grace’s close friend Rex Stevens,

Her attitude was modern. . . . [She and a man would] have a little special time together and then she’d say, “Well, you have to go.” They were so shocked at that because they’d brought a fifth of whatever. Now the fifth is gone, they had their time, and now she’s telling them . . . they’re not staying. She’s got work to do. . . . She was surprised by how shocked they were . . . every time she dropped that on them.58

Grace believed, as André Gide had written, “One should want only one thing and want it constantly.”59 That one thing would never be a man. Grace let Walt go. “Now my days alone have a certain shape to them,” she wrote on July 1, 1955. “I wake about nine, turn on the symphony and have juice, fruit, and a pot of black coffee. Read a bit (still Gide’s Journal), talk on the phone. . . . Then three or four, sometimes five hours on this canvas. . . .”60 Such solitude, however, did not make painting any easier. Grace wept with rage and “hurled” herself at her work, because the image she sought would not surface.61 “My life has been so often in turmoil, why can I not find in my art the peace, the refuge . . . that life doesn’t seem to have for me?” she asked herself.62 Grace believed she understood why Walt had left—he couldn’t bear her life. “Why should he—how could he when I can scarcely bear it myself,” she concluded.63

Having slept off her despair and anger, Grace returned to her canvas, consoled by the notion that despite the difficulties, she was “sure and decided,” not in her bond with another but in herself and her work.64

Endnotes

1. William T. La Moy and Joseph P. McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, 1951‑1955. (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press 2009), p. 151; René d’Harnoncourt, “The Museum of Modern Art Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Year, Final Report” (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1954), p. 9.

2. René d’Harnoncourt, “The Museum of Modern Art Twenty-Fifth Anniversary,” p. 9; Russell Lynes, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Atheneum, 1973), pp. 349, 354.

3. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, pp. 151–52.

4. Ibid., p. 152.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid., 163; joint federal tax return Willem and Elaine de Kooning, 1954, Elaine and Willem de Kooning financial records, 1951–69. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

7. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, p. 157.

8. Ibid., p. 157.

9. Ibid., pp. 153, 154, 160; Exhibitions, Box 37, Grace Hartigan Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries, Syracuse, New York; John Bernard Myers to Larry Rivers, Larry Rivers Papers, MSS 293; Series 1, Subseries A, Box 10, Folder 12, Fales Library and Special Collections. New York University Libraries.

10. Cathy Curtis, Restless Ambition: Grace Hartigan, Painter. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 134–35.

11. “A transcript of a recorded conversation between Linda Nochlin and Molly Nesbit in New York City,” January 28, 2011, vassar.edu/histories/art/nochlin.html.

12. John Patrick Diggins, The Proud Decades: America in War and Peace, 1941–1960. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988), pp. 181, 187; Douglas T. Miller and Marion Nowak, The Fifties: The Way We Really Were. (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1977), p. 277; Deirdre Robson, “ The Market for Abstract Expressionism: The Time Lag between Critical and Commercial Acceptance,” Archives of American Art Journal 25, no. 3 (1985): p. 20.

13. Deirdre Robson, “The Avant-Garde and the On-Guard: Some Influences on the Potential Market for the First Generation Abstract Expressionists in the 1940s and Early 1950s.” Art Journal 47, no. 3 (Autumn 1988), p. 221; Eric Hodgins and Parker Lesley, “The Great International Art Market.” Fortune (December 1955), p. 157.

14. Lynes, The Tastemakers: The Shaping of American Popular Taste. (New York: Dover Publications, 1980), p. 259; Robson, “The Avant-Garde and the On-Guard,” p. 220.

15. Oral history interview with Nathan Halper, July 8–August 14, 1980, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

16. Hodgins and Lesley, “The Great International Art Market,” p. 118; Robson, “The Market for Abstract Expressionism,” p. 20.

17. Hodgins and Lesley, “The Great International Art Market,” pp. 118–19.

18. Ibid., pp. 120–21, 152.

19. Ibid., pp. 121, 152.

20. Ibid.

21. Hilton Kramer, “Interview with Helen Frankenthaler,” Partisan Review 61, no. 2 (Spring 1994), p. 240.

22. Oral history interview with Samuel M. Kootz, April 13, 1964, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institution.

23. Interview with May Tabak Rosenberg, ND, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institutions.

24. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, pp. 167, 170, 171.

25. Exhibitions, Box 30, Grace Hartigan Papers, Syracuse.

26. Thomas B. Hess, “Trying Abstraction on Pittsburgh: The 1955 Carnegie.” ArtNews 54, no. 7 (November 1955), pp. 42, 56. Hess singled out Helen, Joan, and Elaine for mention in his article, calling Helen’s painting “a successful attempt at concretizing experience directly into swirled paint,” Joan’s a “bravura equivalent of a grand landscape,” and Elaine among the “outstanding younger complicators” for introducing figures into a “furnace of color.”

27. Hess, “Trying Abstraction on Pittsburgh,” 40; Tibor de Nagy Gallery Files, Box 28, Folder 1, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institutions; Helen Frankenthaler to Sonya Gutman, Tues., December 14, 1954, Box 1, Folder 6, Sonya Rudikoff Papers; 1935–2000, Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library, Princeton, New Jersey , 1; Carl Belz, “Frankenthaler: The 1950s,” (Waltham, MA: Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, May 10–June 28, 1981), 30; John Elderfield, Painted on 21st Street: Helen Frankenthaler From 1950 to 1959. (New York: Gagosian Gallery, March 8–April 13, 2013), p. 55. ArtNews featured a picture of Helen’s work in its story about the exhibition. Helen’s painting was purchased by Bernard Reis for $300.

28. Dore Ashton, interview by author, September 26, 2014, New York.

29. Cindy Nemser, Art Talk: Conversations with 12 Women Artists. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975), p. 181.

30. Irving Sandler, interview by author, February 3, 2014, New York.

31. Eleanor Munro, Originals: American Women Artists. (New York: A Touchstone Book, Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1982), p. 52; oral history interview with Yvonne Jacquette, June 6, 1989–December 13, 1989, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institution. Painter and printmaker Yvonne Jacquette, who was in her early twenties in the mid-1950s, said after the established women had climbed out on a limb to make art, a younger artist in their wake no longer had to make the “extreme choices” and sacrifices their elders did to be taken seriously. “You didn’t have to be incredible,” she said.

32. Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, (New York: Dell Publishing, Inc., 1964), pp. 41, 122, 124, 152, 158, 161, 165, 170; Margaret Mead, Male and Female: A Study of the Sexes in a Changing World. (New York: Penguin Books, 1981), 290. In 1954, the term “togetherness” was coined by McCall’s magazine to describe a bond in which the woman did not agree to share as much as to submit. From the moment she said, “I do,” a wife’s very person became subsumed by her husband. She might have gone into the ceremony as a woman named Jane Smith but she emerged from it a socially veiled being named Mrs. Tom Jones. Jane, herself, would essentially disappear.

33. Alfred C. Kinsey, Clyde Martin, and Wardell Pomeroy, Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. (New York: Pocketbooks, 1970), pp. 339, 442.

34. Miller and Nowak, The Fifties, pp. 157–58; Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, p. 184.

35. Miller and Nowak, The Fifties, pp. 157–58.

36. Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, pp. 249–50, 255, 315; David Riesman with Nathan Glazer and Reuel Denney. The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978), p. 148. Riesman’s best-selling book also noted this trend. “Today millions of women, freed by technology from any household task, given by technology many ‘aids to romance,’ have become pioneers, with men, on the frontier of sex.” He described such sex as humorless, anxiety producing, and though readily available, “too sacred an illusion.”

37. Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, p. 250.

38. Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, p. 161; Miller and Nowak, The Fifties, p. 256.

39. Mead, Male and Female, pp. 28–29; Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, pp. 128–30.

40. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex. (London: Picador Classics, 1988), p. 69.

41. Ibid., p. 711.

42. Ibid., pp. 713–717, 723.

43. Phyllis Rose, The Norton Book of Women’s Lives. (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1993), pp. 433–34.

44. Marina Pacini, Marisol Sculptures and Works on Paper. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), p. 118.

45. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, p. 171.

46. Ibid., 176.

47. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, p. 175.

48. Jane Freilicher, interview by author, March 16, 2012, New York.

49. John Ashbery to Larry Rivers, May 18, [ca. 1955], Larry Rivers Papers; MSS 293; Series I, Subseries A, Box 1 F19, Fales Library and Special Collections. New York University Libraries; Jane Freilicher, interview by author.

50. Grace Hartigan Journals, May 31, 1955, Box 32, Grace Hartigan Papers, Syracuse.

51. Grace Hartigan Journals, June 6, 1955, Box 32, Grace Hartigan Papers, Syracuse.

52. Grace Hartigan Journals, June 8, 1955, Box 32, Grace Hartigan Papers, Syracuse; Grace Hartigan Journals, June 8, 1955, Box 32, Grace Hartigan Papers, Syracuse.

53. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, pp. 179, 183.

54. Grace Hartigan Journals, June 10, 1955, Box 32, Grace Hartigan Papers, Syracuse; Grace Hartigan Journals, June 15, 1955, Box 32, Grace Hartigan Papers, Syracuse; La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, p. 183.

55. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, pp. 183–84.

56. Ibid., p. 184.

57. Larry Rivers with Carol Brightman, “The Cedar Bar,” New York 12, no. 43 (November 5, 1979), pp. 41–42.

58. Rex Stevens, interview by author, January 27, 2014, Baltimore.

59. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, p. 184.

60. Ibid., 185; Nemser, Art Talk, pp. 168–69.

61. La Moy and McCaffrey, The Journals of Grace Hartigan, p. 187.

62. Ibid., p. 188.

63. Ibid.

64. Ibid.

From the book NINTH STREET WOMEN by Mary Gabriel. Copyright © 2018 by Mary Gabriel. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 98 under the title “Grace and Will.”

[ad_2]

Source link