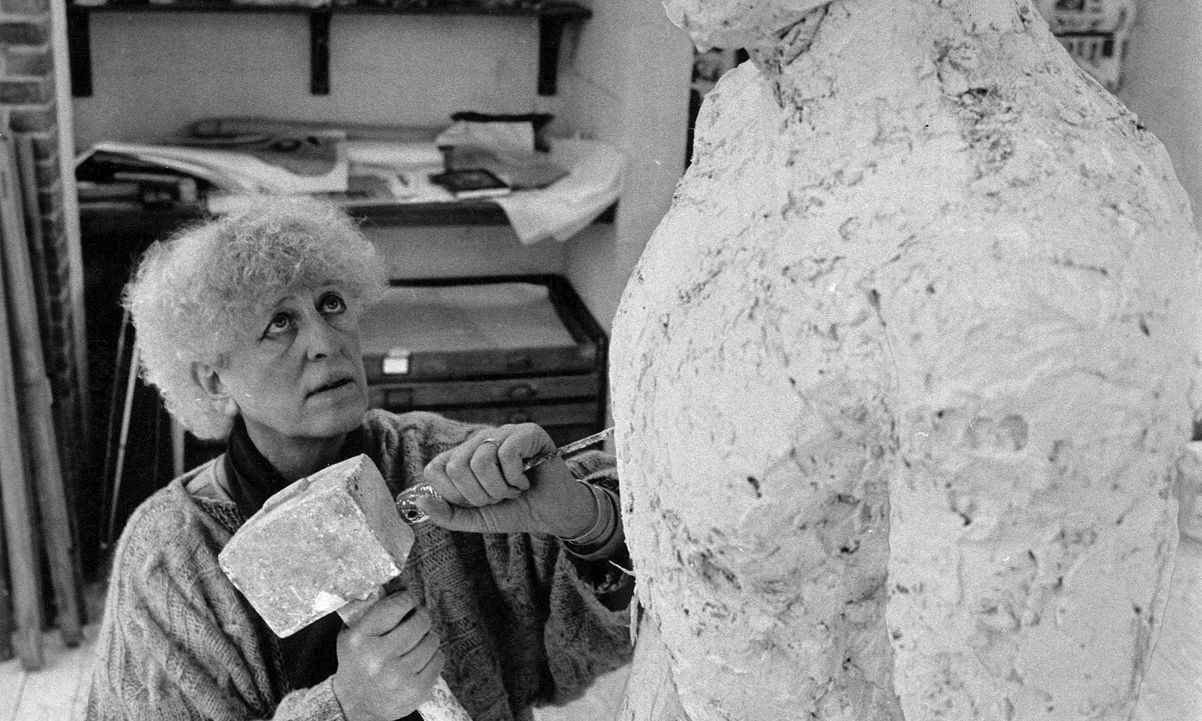

Elisabeth Frink working on the Dorset Martyr group in 1985 © Anthony Marshall/Courtesy of Dorset History Centre. Artist copyright in image kindly approved by Tully and Bree Jammet.

“There must be more works by [Elisabeth] Frink in the streets and the churches and hospitals [of the UK] than by any other sculptor of her generation,” says Annette Ratuszniak, the former curator of the artist’s estate and author of Frink’s sculpture catalogue raisonné. “People in those towns and places are very attached to their Frink. They have a real sense of personal ownership about it.”

The British sculptor’s figurative style was highly successful from early in her career, and she managed to get several major public commissions. But despite Frink’s popularity, in the 1960s figurative work began to go out of fashion in the art world with the advent of abstraction and Pop art. “She tried abstraction but it didn’t work for her,” Ratuszniak says. “She was very sad when drawing was sidelined in [British] art schools,” she adds, citing it as a reason for Frink’s retreat to France in the late 1960s.

Frink's Riace III (1986) © John-Paul Bland/Courtesy The Ingram Collection. Artist copyright in image kindly approved by Tully and Bree Jammet

In the past decade, however, several museum and gallery shows point to a reappraisal. Frink’s explorations of the natural world and of humanity—and sometimes inhumanity, with sculptures depicting victims of war and dark-glassed dictators—chime with contemporary concerns. “There are some lovely words from Frink where she talks about her Baboon works, the baboon family, how ordered it is, in such contrast to human beings, how we could learn so much from that sort of dignity of the animal,” says Lucy Johnston, the co-curator—along with Ratuszniak—of Elisabeth Frink: A View from Within, which opens this month at the Dorset Museum & Art Gallery. “[Frink] talks about the dignity of the horse, and that really comes across in her Standing Horse sculpture,” Johnston adds.

The new exhibition will include more than 80 sculptures, graphic works, personal mementos, letters and photographs, drawing on studio material and archives from Woolland, the country manor house in the south west of England where the artist lived and worked for the two decades before her death in 1993. The show will also combine pieces from the Dorset Museum’s own large collection, including never previously exhibited plaster precursors of her bronzes, with important sculptures from the Yorkshire Sculpture Park and the Ingram Collection of Modern British Art.

Frink's Standing Horse (1993) Dorset Museum collection. Artist copyright in image kindly approved by Tully and Bree Jammet

A distribution of the Frink estate to a dozen selected museums has fed the recent shows, fulfilling the wishes of her son and executor Lin Jammet, who died in 2017. Exhibitions at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich in 2018 and the Holburne Museum in Bath last year were built on estate donations. The Dorset Museum itself received more than 300 works in 2020, including 31 bronzes, more than 100 prints and drawings and original plasters together with her studio tools and equipment. “We’ve been given this amazing donation,” Johnston says. “Things that, as well as showing her art processes, will bring a very personal view of Elizabeth Frink at Woolland.”

• Elisabeth Frink: A View from Within, Dorset Museum & Art Gallery, Dorchester, 2 December-21 April 2024