[ad_1]

LOS ANGELES ― David Allen smiles widely as he holds up a small blue photo album stuffed with drawings.

“See, this one is probably my favorite!” Allen, 32, yells over the reggae playing from his desk at the festival entrance. He’s showing off an original tattoo design. “It looks like a bird, but if you rotate it a quarter, it looks like a chicken. And if you rotate it again, it can be a horse or a catfish!”

Allen had never been anywhere like Skid Row until last year.

He was once a dancer in a successful hip-hop group, but an injury forced him to stop dancing almost a decade ago. He moved from Miami to Los Angeles in hopes of becoming a tattoo artist. Like many at the annual Artist Festival in Gladys Park, art helps him express his true self. His latest drawing is of a cub from “The Lion King,” crouched and ready to leap at a butterfly. It looks almost as gleeful as Allen himself does as he explains his work, which includes many cartoons and Disney characters.

“I might be a grown man, but I like to play a lot, and that’s where I use my mind’s age and put that out on the paper,” he says.

Gladys Park, in the heart of Skid Row, is an area where many Los Angeles residents rarely venture. There is a perception that this is a dark and disturbing place, associated with vagrancy, violence and drug abuse. But those who dig deeper will discover that it contains a supportive, dynamic community.

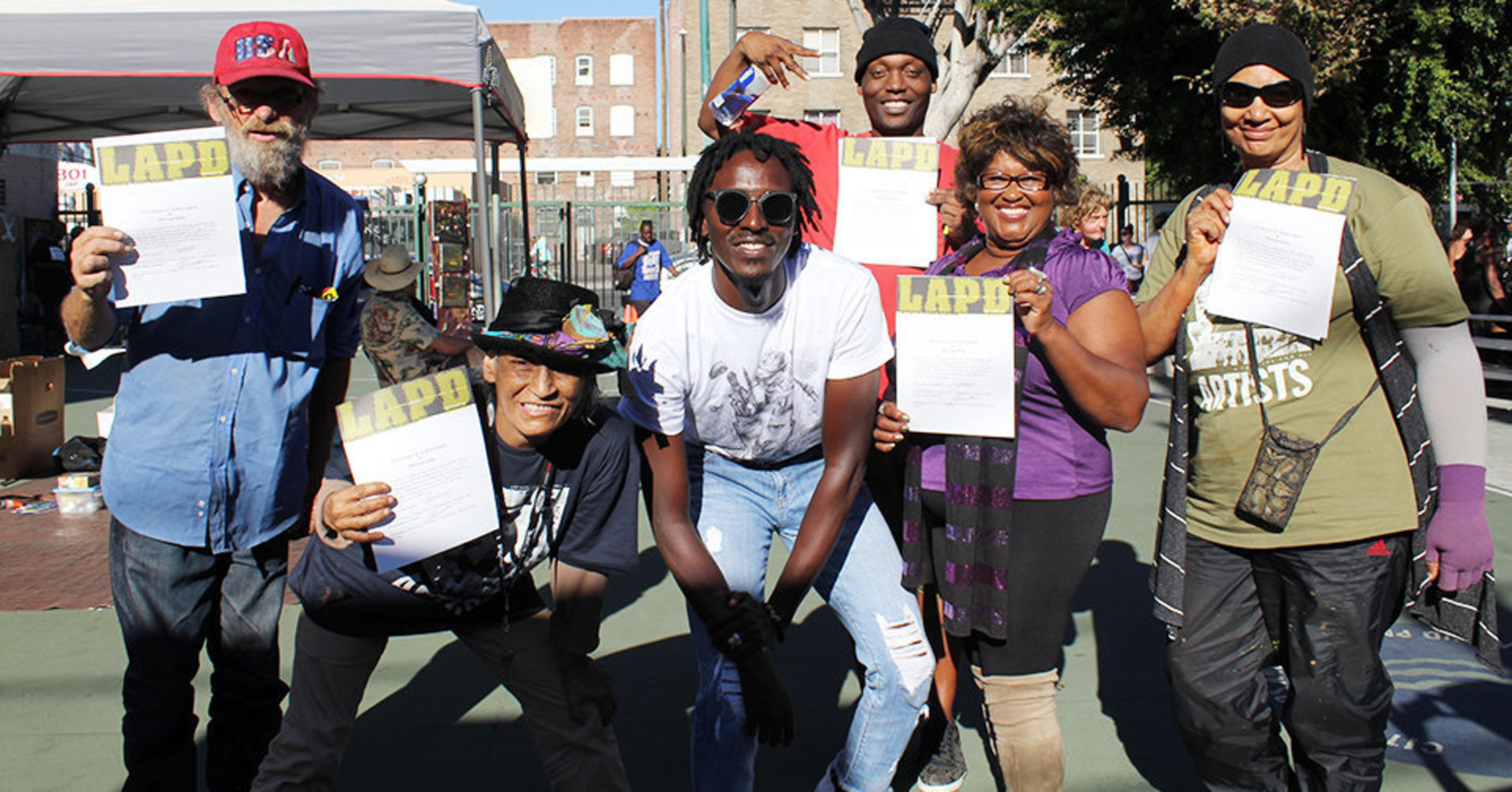

For two days last October, artists like Allen set up their easels and brushes in Gladys Park for the eighth annual Skid Row Arts Festival. The park is squeezed into the western corner of Gladys Avenue and East 6th Street, bounded by two walls covered with murals and fliers profiling performers.

The Los Angeles Poverty Department, an organization that’s pioneered extensive art initiatives for homeless communities in the city, runs the festival, which includes artwork, spoken word and music. Henriëtte Brouwers, the program’s associate director and producer, helped organize the first festival in 2010 and has watched the Skid Row art community flourish.

“We have been active in showing that there is a community where people take care of each other,” Brouwers said.

The art scene here began in 1985, when John Malpede founded the Los Angeles Poverty Department. At the time, it was the only arts program for homeless people in Los Angeles. Today, according to Brouwers, there are more than 800 registered artists of Skid Row, part of what some community members like to call “the biggest recovery community anywhere.”

“Art can work as an organizing research principle, as an empowering tool and as a way to bring a community together,” Brouwers said.

Mariana Valles, or “Blackie” as she’s known to others in the neighborhood, is an abstract painter. She doesn’t want anybody to see anything in particular in her artwork ― she simply wants people to feel something.

“It’s about dredging up what’s inside you,” Valles said. “My artwork is really aggressive. You may even see a bit of joy, anger, wrath.”

A proud member of the Skid Row community, Valles enthusiastically shows off the work of fellow artists.

“All of this is incredible. I’m hard to impress,” she said. “But these people have had no college, no schooling. It’s just a gift straight from their heart and I am impressed!”

Valles grew up in Arkansas and took a Greyhound bus to Los Angeles with her family when she was 12. At 42, she developed a severe drug addiction and lost her family, friends and home. She arrived at Skid Row five years before any of the art programs were established.

“I’ve seen people who were aimless, no goals,” she said. “And then they got into the art process and started having some self-worth, and feeling like, ‘Hey, I’m good at this! I can do something, I can contribute to society.’”

Working on the streets can be dangerous. Artists have been robbed, and had bags of artwork or art supplies stolen or destroyed. Robert Tolbert, 55, once had to wrestle his bag of drawings away from a man who tried to rob him as he was walking to the park.

“When people are poor in situations where there is very little hope, when they don’t have a job and they have very little money or no money at all, in desperate situations they do desperate things,” Tolbert said. “So I couldn’t really get mad at the young man for trying to take it. I guess if I were in his position I would try it too.”

The trauma many in Skid Row are dealing with is undeniable, and events like the art festival won’t instantly change the public perception of homelessness. But Brouwers believes it opens the door to empathy.

“Art is for everybody, really,” she said. “In that sense it’s therapeutic, but it also connects them with other people if they can share it with them.”

Skid Row’s art events attract people from all over the world. At a table adjacent to the stage, Djibril Drame is teaching a photography workshop to 10 community members, including Valles. Those who have phones are passing them around so everyone gets a chance to practice taking a portrait.

“Look how focused everybody looks,” Drame says, looking around the group with a wide smile. “Art is really the element that connects people.”

This is Drame’s second year at the festival. He travels and teaches photography workshops to children and adults around the world.

“Visual literacy can be the best tool to transmit education ― way better than writing,” he says.

“A lot of times the people on Skid Row are looked at as if what is happening to them is their personal failure,” Brouwers said. “And really what [our organization] is trying to do is to connect the person’s experience with the social forces that have created this experience.”

In the past, the Los Angeles Poverty Department has put on plays that addressed the overcrowded prison system and the war on drugs. Next spring, Brouwers says, they are going to focus on Skid Row’s safety ― an issue that plays a key role in creating a supportive community.

One regular aspect of life in Skid Row is conspicuously absent from the festival: law enforcement. The only security provided is a pair of guards hired by the Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department. They stay outside in a car unless invited in, because “they know that the community doesn’t want them inside,” Brouwers said. There were no police in the park all weekend, which organizers hope demonstrates that law enforcement isn’t always necessary to have a safe community. People here can take care of each other.

“People especially on Skid Row are very sensitive,” Brouwers said. “Most people have experienced big traumas in their lives, and for a lot of people, art is a way to express what they are feeling.”

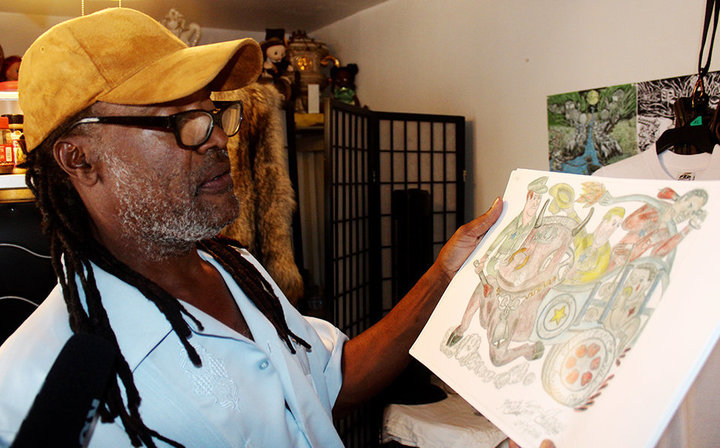

Reinaldo Sanchez lived in Skid Row until six months ago. As an artist, he draws what he sees ― including police violence.

“What he feels and what life is, and what’s being and what’s to come, he’s gonna draw it all,” said his partner, Graciela Fernandez.

Sanchez and Fernandez, who both immigrated from Cuba, now share an apartment. They have known each other since Sanchez first came to Los Angeles, but Fernandez said she didn’t recognize his artistic talents until they were living in Skid Row together.

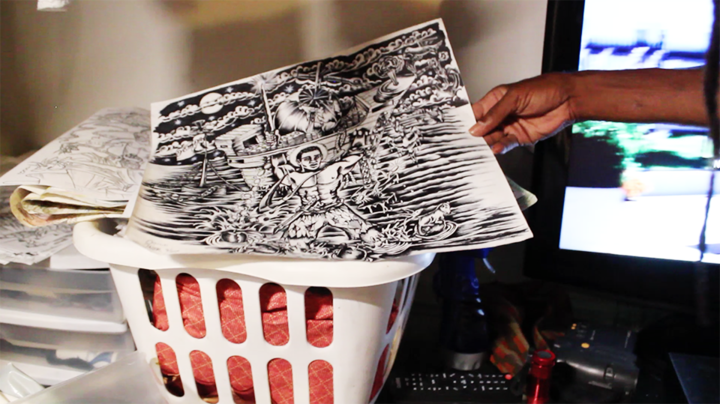

Sanchez’s illustrations show a constant struggle between the police and those who live in the Skid Row area. One drawing shows a young African-American man jumping over a building, the ground below him soaked with blood. The drawing, Sanchez says, refers to a real-life incident where highway patrol officers chased a young man off a freeway and then claimed he’d simply jumped. (It’s not clear whether the incident Sanchez describes actually happened.) Other drawings depict police arresting or harming people experiencing homelessness.

“I want to share my work and my experiences with the world and with other people, to show them what is going on in places they might not know about,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez began taking videos with his cellphone when he lived in Skid Row as a way to hold police accountable.

“When an officer sees you taking that video, it’s like being like, ‘Hey! I’m here!’ and saying, ‘Yeah, I’m going to film what you are doing, because nobody else is caring,’” he said.

He began drawing as a child in Cuba, in the aftermath of the revolution. It allows him to work through painful situations.

When he was living in Skid Row, one of Sanchez’s friends helped him print T-shirts with his paintings on them. His plan was to sell them and share them with the surrounding community, but they were stolen from his tent. He would keep his drawings under his pillows, but those were stolen as well. He estimates he’s had hundreds of drawings stolen.

“These messages, they are important,” he said. “They don’t just relate to what I have seen on Skid Row, but they connect everything that I see with the current events that are going on.”

Although Sanchez can be a man of few words, his artwork gives him a powerful voice, Fernandez said.

“Sometimes he’s just not talkative, but he expresses what he feels,” she said. “It’s a great therapy for somebody who needs to just escape.”

This story is part of the series Homeless on the Streets of L.A., a four-month investigation by students at USC Annenberg’s Reporting on the Homeless class. The project, overseen by veteran journalists Mary Murphy and Sandy Tolan, continues through early 2019. Contact [email protected] or [email protected] for more info.

[ad_2]

Source link