Kazakhstan Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 2024

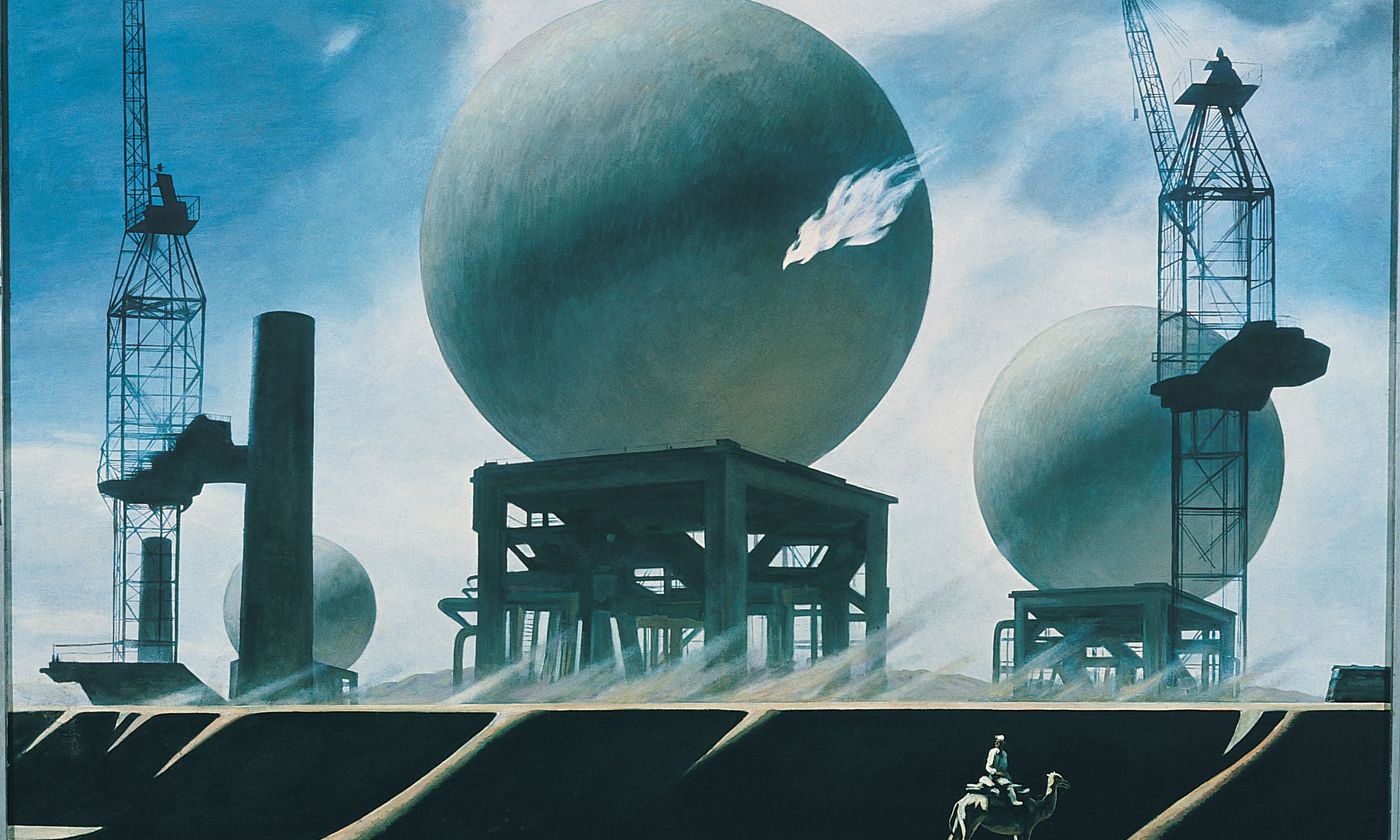

Kamil Mullashev, Over the White Desert (1978); cardboard, tempera. Kasteev State Museum of Arts, Almaty, Kazakhstan

The Venice Biennale has established itself as an event that sets a new tonality for art, like a sacred ritual that renews the life of art every two years. Reflecting the innovative ideas and anxieties of our turbulent time, artistic practices offer us a chance to reconsider stale narratives from a completely unexpected position. One such striking example is the Kazakhstan pavilion, which unfolds a story around the ancient legend of Jerūiyq, the Promised Land where time stopped, giving eternal life, and the souls and thoughts of people filled with pure radiance.

The Republic of Kazakhstan, has a remarkable geography, sandwiched between two giants, Russia and China: imagine how much effort it takes both to establish an identity and also to be able to communicate it. As a state, it has been independent since 1991, but its history begins in the mists of time. It is from this mixture of dreams and roots that the show Jerūiyq: a Look Beyond the Horizon was born. In the Kazakh pavilion, this dichotomy is skilfully reconciled: the past and the future are intertwined, the history of an ancient nation is told and at the same time the aspirations of a very young nation with a rich history are demonstrated.

Some artists' work is particularly striking. Yerbolat Tolepbay's transcendental large-scale painting immerses the viewer in the journey of the New Child, which the artist created in 2023-24 as a reference to his very strong work presented in the pavilion, Akyr Zaman ("the end of the world", 1985). Confronted with geopolitical battles, new military conflicts or the Covid-19 pandemic, many have at least once thought about the end of the world. But how can we move away from our linear perception of history and look at time through the eyes of the heirs of a nomadic civilisation? The artist finds a way by presenting this state of tension in two sharp forms that are in confrontation, opening a portal to an image of hope for a new generation, as if sending the viewer into hyperspace, into other worlds where humanity may still have a chance.

A still from Anvar Musrepov's video essay Alastau (2024)

Sergey Maslov, who died in 2002 at the age of 50, was a visionary artist, misunderstood and a source of fascination for his life on the edge. He was drawn to spiritualism and black magic, and skilfully created fake news stories about himself that shocked society while fuelling myth: from a fake suicide to an imaginary relationship with Whitney Houston.

Maslov has had a huge influence on contemporary Kazakh art and has been a source of inspiration for many generations, and his echoes can also be seen in the very powerful video Alastau, by the young Anvar Musrepov, a piece that takes us to a distant future where even the sun has been extinguished and people who survived the apocalypse live in tribes and practise ancestral rituals. One can sense a dialogue with Tolepbay's Akyr Zaman here: a fascinating vision of time as something circular and of history being rewritten, returning to its origins and erasing the mistakes made over the centuries.

By definition, the Biennale is a temple of modernity, and it is here that the legend of Jerūiyq is presented—it is nothing less than a metaphor breaking our templates for life and imagining an alternative future from the perspective of Kazakhstani artists.