[ad_1]

American Artist, Blue Life Seminar (still), 2019.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

In 2013, one artist had their name legally changed to American Artist. “I was very interested in reframing the definition of an American artist,” that artist, who uses the last name Artist and prefers they/them pronouns, said. “If I make that my name, now I am it.” Completing the name change involved visiting a California court, publishing an official notice in a newspaper (“I chose the cheapest one,” they said), and setting up a hearing. No officials raised any objections.

Artist was messing with the stereotypes that attach to the phrase “American artist,” which calls to mind, for some, famous white men living in New York during the postwar era, like Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. What would it mean for a black individual, like Artist, to adopt the title? Recalling the name-change process recently, Artist said, with a laugh, “I am American Artist now, so I guess that’s what an American artist is.”

Though their name-change isn’t a work per se, it is an example of Artist’s sly, slippery practice, which has taken the form of digital works, videos, and sculptures that take on the shifting nature of identity in the internet age. (It’s worth noting that Googling American Artist is a Sisyphean task.) Often, Artist draws out connections between systemic forms of racism and new technological developments—one body of work, for example, addressed the whiteness of new products put out by Silicon Valley by simultaneously thinking through the look of iPhones and the racial demographics of technology companies. “I’ve started to think about anti-blackness as being sort of algorithmic, in that it’s embedded in the firmware of American society,” they said. “It’s a constantly reproducing and evolving thing, and it’s always doing what it’s supposed to do.”

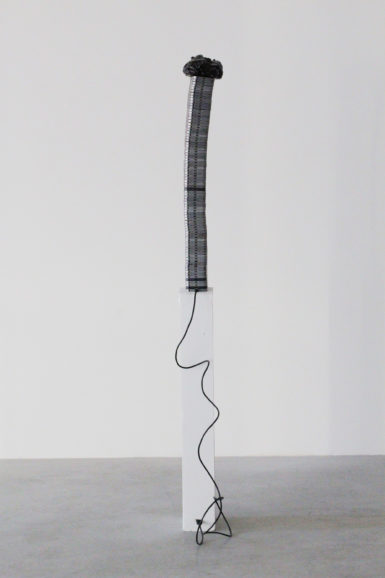

American Artist, Untitled (Too Thick), 2018.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HOUSING, BROOKLYN

This weekend, at the New Museum in New York, at a conference put on by the art-and-technology organization Rhizome called Seven on Seven, Artist will unveil their latest work, an infomercial for a faux product called Ally AI that they produced in collaboration with Rashida Richardson, the director of policy research at the research center AI Now. “It’s this product that would help someone to be less problematic,” Artist said, explaining that one could ask the AI how to behave in a politically correct way when faced with a difficult situation. Part farce and part commentary, the product would take the place of “having to know any people of color to check them, so they invest in a software instead of becoming a better person,” they said.

Artist, 29, is one of the most closely watched emerging talents in the New York art world, particularly in art-tech circles, and their profile will soon rise further. They will have their first institutional solo show later this year at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco in May, and it will be followed by another one-person show at the Queens Museum in October. One of their most memorable outings ran through last week at Koenig & Clinton gallery in Brooklyn, where the full breadth of their vision was on display in a show that dealt with police violence, social-media activism, and the strange nature of avatars, digital images meant to represent technology users that exist only as shells online.

On a recent morning ahead of that show’s opening, Artist could be found in the basement of the Abrons Art Center on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where they are currently an artist-in-residence. Surrounding them were new sculptures for the exhibition—desks with fabric appended to them, along with chairs whose legs have been extended. Artist was at work on a new video for the exhibition, “I’m Blue (If I Was █████ I Would Die),” which featured a computer-generated version of Doctor Manhattan, a muscular blue mutant from the graphic novel Watchmen, and text from a manifesto by Christopher Dorner, a black LAPD officer who, after realizing that the ideals guiding the police force weren’t what he thought they were, staged several shootings in California, killing family members of policemen in some cases. “I am a man who completely lost faith in the system,” Doctor Manhattan’s avatar says, its blank white eyes staring into the camera, “when the system betrayed and libeled me.”

For Artist, the show was about the complicated connection between race and the police force in the United States. “The show is a response to the Blue Lives Matter movement, and also how, in 2018, [police officials] pushed forward this law called the Protect and Serve Act of 2018, which further protects police,” Artist said of a bill put forward last year. “The wording of it is almost like hate crime law. It’s basically a response to police feeling like they’re being targeted, and that came up after the Black Lives Matter movement. They felt threatened, as if people are hunting them. That raises questions about identity in general—how you can identify as blue, which is not anyone’s actual identity?”

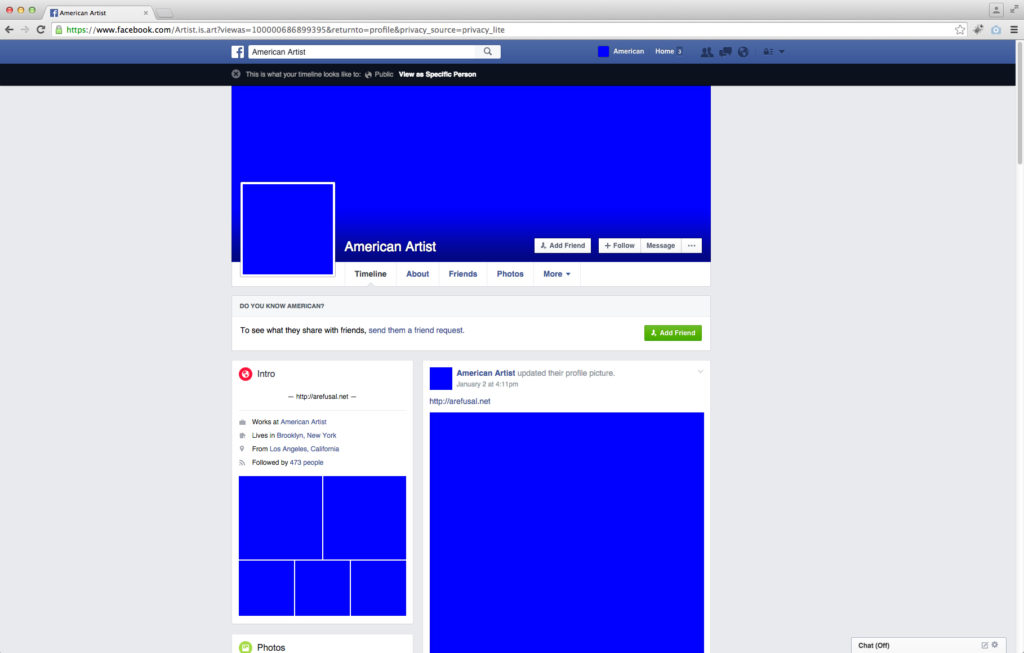

American Artist, A Refusal, 2015–16.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

The indefinability of identity today has been at the center of Artist’s work from the very beginning. For one of their earliest projects, A Refusal (2015–16), they archived every photo on their Facebook page, printed the pictures in an album, then replaced the digital images with blue squares. In doing so, curious visitors to Artist’s page couldn’t see who they were or what was happening in their life. This work has affinities with pieces by so-called post-internet artists—art about the circulation of images by Metahaven, Constant Dullaart, and many more—but it has none of the slickness associated with those artists’ work.

And, if anything, Artist’s work rejects the finish-fetish aesthetic that commonly accompanies work about digital technology in the age of Web 2.0. Artist’s show at Housing gallery in Brooklyn last year, “Black Gooey Universe,” included technological objects that seemed to leak dark fluids—a keyboard that dripped with black oil, stacked aluminum casts of phones that were topped with a tumorous-looking mound of silicone, polyurethane, and asphalt. In a related essay, Artist wrote that “black gooey [is] antithetical to the values of the white screen”; they related this inquiry to Fred Moten’s theories about race. Anti-blackness, Artist suggested, exists equally in the iPhones we use daily and the sets of politics we use to guide our lives.

Artist has so far exhibited a deft ability to take an object and render it unusable or gross, as they did with iPhones for the Housing show. “I was essentially thinking of it as a phone if you extruded it to the point where it’s not physically usable,” Artist said, speaking of the stacked-phones piece and explaining that, in part, their interest in assisted readymades stems from artist David Hammons. “I was thinking about how he removed himself—at least his physical self—from the context of art,” Artist said. “As far as I know, he doesn’t have an internet presence. What does it mean to take up these same gestures and think of them in the context of working after the internet?”

As it happens, Artist has appropriated Hammons’ name for their Twitter, which is called Hammons Current Day. Asked about that name, Artist thought for moment and said, “I can be David Hammons on the internet.”

Correction 4/26/19, 3:10 p.m.: An earlier version of this article misstated the state where Artist changed their name. They changed their name in California, not New York, where they are currently based. The post has been updated to reflect this.

[ad_2]

Source link