[ad_1]

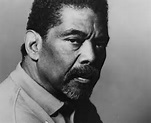

Alvin Ailey (January 5, 1931 – December 1, 1989) was an African-American choreographer and activist who founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in New York City. He is credited with popularizing modern dance and revolutionizing African-American participation in 20th-century concert dance. His company gained the nickname “Cultural Ambassador to the World” because of its extensive international touring. Ailey’s choreographic masterpiece Revelations is believed to be the best known and most often seen modern dance performance. In 1977, Ailey was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP.[1] He received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1988, just one year before his death. In 2014, President Barack Obama selected Ailey to be a posthumous recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[2]

Early years

Ailey was born to his 17-year-old mother, Lula Elizabeth Ailey, in Rogers, Texas. His father, also named Alvin,[3] abandoned the family when Alvin was only six months old. Like many African Americans living in Texas during the Great Depression, Ailey and his mother moved often and had a hard time finding work.

Ailey grew up during a time of racial segregation, violence and lynchings against African Americans. Early experiences in the Southern Baptist church and juke joints instilled in him a fierce sense of black pride that would later figure prominently in Ailey’s signature works.[4][5]

In the fall of 1942, Ailey’s mother, in common with many African Americans, migrated to Los Angeles, California, where she heard of lucrative work supporting the war effort. Ailey, aged 11, joined his mother later by train, having stayed behind in Texas to finish out the school year. Ailey’s first junior high school in California was located in a primarily white school district. As one of the few black students, Ailey felt out of place because of his fear of whites, so the Aileys moved to a predominantly black school district. He matriculated at George Washington Carver Junior High School, and later attended the Thomas Jefferson High School. He sang spirituals in the glee club, wrote poetry, and demonstrated a talent for languages. He regularly attended shows at Lincoln Theater and the Orpheum Theater. Ailey did not become serious about dance until in 1949 his school friend Carmen De Lavallade introduced him to the Hollywood studio of Lester Horton. Horton would prove to be Ailey’s major influence, becoming a mentor and giving him both a technique and a foundation with which to grow artistically.[6][page needed]

Horton’s school taught a wide range of dance styles and techniques, including classical ballet, jazz, and Native American dance. Alvin quickly fell in love with dance. Horton’s school was also the first multi-racial dance school in the United States.[6][page needed] Ailey was, at first, ambivalent about becoming a professional dancer. He had studied Romance languages at various universities in California,[7] but was restless, academically, and took courses as well in the writings of James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, and Carson McCullers[citation needed]. He moved to San Francisco to continue his studies in 1951. There, he met Marguerite Johnson, who later changed her name to Maya Angelou.[8] They occasionally performed a nightclub act called “Al and Rita”. Ailey earned a living waiting tables and dancing at the New Orleans Champagne Supper Club. Eventually, he returned to study dance with Horton in southern California.[6][page needed]

The Horton Dance Company

He was introduced to the company through Carmen, a lifelong friend. At the age of 22 Ailey began full-time study at Horton’s school. He joined Horton’s company in 1953, making his debut in Horton’s Revue Le Bal Caribe. It was during this period that Ailey performed in several Hollywood films. Like all of Horton’s students, Ailey studied other art forms, including painting, acting, music, set design, and costuming, as well as ballet and other forms of modern and ethnic dance.

When Horton died in November 1953 the tragedy left the company without an artistic director. The company had outstanding contracts that required and desired new works. When no one else stepped forward, Ailey assumed the role of artistic director. Despite his youth and lack of experience (Ailey was only 22 years old and had choreographed only one dance in a workshop) he began choreographing, directing scene and costume designs, and running rehearsal and he also directed one of the shows for the company.

New York

In 1954, he and his friend Carmen De Lavallade were invited to New York to dance in the Broadway show, House of Flowers by Truman Capote, starring Pearl Bailey and Diahann Carroll. He also appeared in Sing, Man, Sing (1956, starring Harry Belafonte) and in Jamaica (1957) with Lena Horne and Ricardo Montalbán. The New York modern dance scene in the fifties was not to Ailey’s taste. He observed the classes of modern dance contemporaries such as Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and José Limón. He felt Graham’s dancing “finicky and strange” and disliked the techniques of both Humphrey and Limón. Ailey expressed disappointment at not being able to find a technique similar to Horton’s. Not finding a mentor, he began creating works of his own.

Alvin Ailey Dance Theater

Ailey formed his own group, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, in 1958. The group presented its inaugural concert on March 30, 1958. Notable early work included Blues Suite, a piece deriving from blues songs. Ailey’s choreography was a dynamic and vibrant mix growing out of his previous training in ballet, modern dance, jazz, and African dance techniques. Ailey insisted upon a complete theatrical experience, including costumes, lighting, and make-up. A work of intense emotional appeal expressing the pain and anger of African Americans, Blues Suite was an instant success and defined Ailey’s style.

Revelations performed by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre in 2011

For his signature work, Revelations, Ailey drew upon his “blood memories” of Texas, the blues, spirituals, and gospel. These forces resulted in the creation of his most popular and critically acclaimed work. Ailey originally intended the dance to be the second part of a larger, evening-length survey of African-American music which he began with Blues Suite.

Although Ailey created 79 works for his dancers, he maintained that his company was not merely a showcase for his own work. Today, the company continues Ailey’s vision by performing important works from the past and commissioning new additions to the repertoire. In all, more than 200 works by over 70 choreographers have been performed by the company.

Ailey was proud that his company was multi-racial. While he wanted to give opportunities to black dancers, who were frequently excluded from performances by racist attitudes at the time, he also wanted to rise above issues of negritude. His company always employed artists based solely on artistic talent and integrity regardless of their race.

Ailey continued to create work for his own company and also choreographed for other companies.

In 1962 the U.S. State Department sponsored the Alvin Ailey Dance Company’s first overseas tour. Ailey was suspicious of his government benefactors’ motives. He suspected they were propagandistic, seeking to advertise a false tolerance by showcasing a modern Negro dance group.

In 1970, Ailey was honored by a commission to create The River for the American Ballet Theatre (ABT). He viewed The River, which he based on the music of composer Duke Ellington, as a chance to work with some of the finest ballet dancers in the world, particularly with the great dramatic ballerina Sallie Wilson. The ABT, however, insisted that the leading male role be danced by the only black man in the company, despite misgivings by Ailey and others about the dancer’s talent.

Cry (1971) was one of Ailey’s greatest successes. He dedicated it to his mother and black women everywhere. It became a signature piece for Judith Jamison.

The Alvin Ailey Dance Theater was constructed by Tishman Realty and Construction Corporation of New York, Manhattan’s largest builder.

Technique

Ailey made use of any combination of dance techniques that best suited the theatrical moment.[9] Valuing eclecticism, he created more a dance style than a technique. He said that what he wanted from a dancer was a long, unbroken leg line and deftly articulated legs and feet (“a ballet bottom”) combined with a dramatically expressive upper torso (“a modern top”).[10] “What I like is the line and technical range that classical ballet gives to the body. But I still want to project to the audience the expressiveness that only modern dance offers, especially for the inner kinds of things.”[9]

Ailey’s dancers came to his company with training from a variety of other schools, from ballet to modern and jazz and later hip-hop. He was unique in that he did not train his dancers in a specific technique before they performed his choreography. He approached his dancers more in the manner of a jazz conductor, requiring them to infuse his choreography with a personal style that best suited their individual talents. This openness to input from dancers heralded a paradigm shift that brought concert dance into harmony with other forms of African-American expression, including big band jazz.[9]

In 1992 Alvin Ailey was inducted into the National Museum of Dance’s Mr. & Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, NY.

Personal life

Ailey kept his life as a dancer a secret from his mother for the first two years.[5]

For a time during the 1950s, Ailey was romantically involved with political activist David McReynolds.[11]

Ailey died on December 1, 1989 at the age of 58.[12] To spare his mother the social stigma of his death from HIV/AIDS, he asked his doctor to announce that he had died of terminal blood dyscrasia.[5]

Choreography

- Cinco Latinos, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Kaufmann Concert Hall, New York City, 1958.

- Blues Suite (also see below), Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre,Kaufmann Concert Hall, 1958.

- Revelations, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Kaufmann ConcertHall, 1960.

- Three for Now, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Clark Center, New York City, 1960.

- Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Clark Center, 1960.

- (With Carmen De Lavallade) Roots of the Blues, Lewisohn Stadium, New York City, 1961.

- Hermit Songs, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1963.

- Ariadne, Harkness Ballet, Opera Comique, Paris, 1965.

- Macumba, Harkness Ballet, Gran Teatro del Liceo, Barcelona, Spain,1966, then produced as Yemanja, Chicago Opera House, 1967.

- Quintet, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Church Hill Theatre, Edinburgh Festival, Scotland, 1968, then Billy Rose Theatre, New York City, 1969.

- Masekela Langage, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, American Dance Festival, New London, Connecticut, 1969, then Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York City, 1969.

- Streams (also see below), Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Brooklyn Academy of Music, 1970.

- Gymnopedies, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Brooklyn Academy of Music, 1970.

- The River, American Ballet Theatre, New York State Theater, 1970.

- Flowers, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, ANTA Theatre, 1971.

- Myth, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, New York City Center, 1971.

- Choral Dances, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, New York City Center, 1971.

- Cry, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, New York City Center, 1971.

- Mingus Dances, Robert Joffrey Company, New York City Center, 1971.

- Mary Lou’s Mass, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, New York City Center, 1971.

- Song for You, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, New York City Center, 1972.

- The Lark Ascending, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, New York City Center, 1972.

- Love Songs, Alvin Ailey City Center Dance Theater, New York City Center, 1972.

- Shaken Angels, 10th New York Dance Festival, Delacorte Theatre, New York City, 1972.

- Sea Change, American Ballet Theatre, Kennedy Center Opera House, Washington, D.C., 1972, then New York City Center, 1973.

- Hidden Rites, Alvin Ailey City Center Dance Theater, New York City Center, 1973.

- Archipelago, 1971,

- The Mooche, 1975,

- Night Creature, 1975,

- Pas de “Duke“, 1976,

- Memoria, 1979,

- Phases, 1980

- Landscape, 1981.

Stage

Acting and dancing

- (Broadway debut) House of Flowers, Alvin Theatre, New York City, 1954 – Actor and dancer.

- The Carefree Tree, 1955 – Actor and dancer.

- Sing, Man, Sing, 1956 – Actor and dancer.

- Show Boat, Marine Theatre, Jones Beach, New York, 1957 – Actor and dancer.

- Jamaica, Imperial Theatre, New York City, 1957 – Actor and lead dance.

- Call Me By My Rightful Name, One Sheridan Square Theatre, 1961 – Paul.

- Ding Dong Bell, Westport Country Playhouse, 1961 – Negro Political Leader.

- Blackstone Boulevard, Talking to You, produced as double-bill in 2 by Saroyan, East End Theatre, New York City, 1961-62.

- Tiger, Tiger, Burning Bright, Booth Theatre, 1962 – Clarence Morris.

Stage choreography

- Carmen Jones, Theatre in the Park, 1959.

- Jamaica, Music Circus, Lambertville, New Jersey, 1959.

- Dark of the Moon, Lenox Hill Playhouse, 1960.

- (And director) African Holiday (musical), Apollo Theatre, New York City, 1960, then produced at Howard Theatre, Washington, D.C., 1960.

- Feast of Ashes (ballet), Robert Joffrey Company, Teatro San Carlos, Lisbon, Portugal, 1962, then produced at New York City Center, 1971.

- Antony and Cleopatra, Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, New York City, 1966.

- La Strada, first produced at Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, 1969.

- (With others) Mass, Metropolitan Opera House, 1972, then John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia Academy of Music, both 1972.

- Carmen, Metropolitan Opera, 1972.

- Choreographed ballet, Lord Byron (opera; also see below), Juilliard School of Music, New York City, 1972.

- Four Saints in Three Acts, Piccolo Met, New York City, 1973.

Director

- (With William Hairston) Jerico-Jim Crow, The Sanctuary, New York City, 1964, then Greenwich Mews Theatre, 1968.

Film

Film appearances

- (Film debut) Dancer, Lydia Bailey, Twentieth-Century Fox, 1952

- Dancer, Carmen Jones, Twentieth-Century Fox, 1954

Film choreography

- Choreographer (with others), The Turning Point, Twentieth-Century Fox, 1977.

Television

Television appearances

- Dancer (with Horton Company), Party at Ciro’s (also see below), 1954.

- Dancer (with Horton Company), Red Skelton Show (also see below), CBS, 1954.

- (With Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre) Dave Garroway Today Show, NBC, 1959.

- (With Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre) Look Up and Live, CBS, 1962.

- (With Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre) Camera Three, CBS, 1962-63.

- America’s Tribute to Bob Hope, NBC, 1988.

- A Duke Named Ellington (also known as American Masters), PBS, 1988.

- The Kennedy Center Honors: A Celebration of the Performing Arts, CBS, 1988.

- 16th Annual Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, syndicated, 1989.

- Bill Cosby Salutes Alvin Ailey, NBC, 1989.

Television choreography

- The Jack Benny Show, CBS, 1954.

- Red Skelton Show, CBS, 1954.

- Parade, CBC, 1964.

- Alvin Ailey: Memories and Visions, PBS, 1974.

- “Blues Suite”, Three by Three, PBS, 1985.

- “Revelations”, The Kennedy Center Honors: A Celebration of the Performing Arts, CBS, 1988.

- “Revelations”, Bill Cosby Salutes Alvin Ailey, NBC, 1989.

- “For Bird – With Love”, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Steps Ahead, PBS, 1991.

- Also contributed choreography for Party at Ciro’s, 1954.

- Choreographed Ailey Celebrates Ellington, 1974 and 1976, Solo for Mingus, 1979, and Memoria, 1979.

Adaptations

- Blues Suite, Masekela Langage, Streams, and the ballet of Lord Byron have been filmed.

Tributes

In 2012 Ailey was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display which celebrates LGBT history and people.[13]

A crater on Mercury is named for him as well.

[ad_2]

Source link