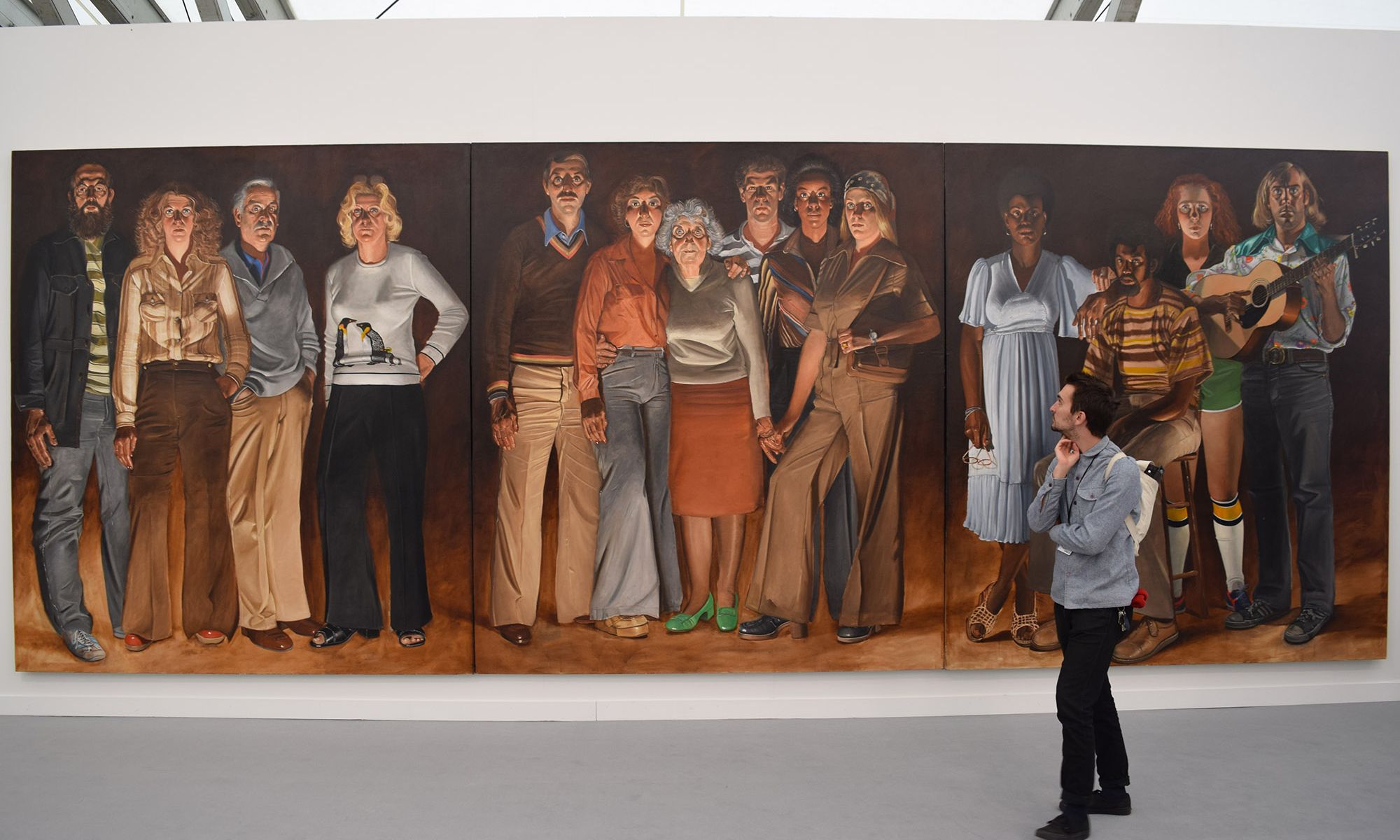

Alfred Leslie's Americans, Youngstown, Ohio (1977-78) on display on Bruce Silverstein gallery's stand at Frieze New York in 2017 © Benjamin Sutton

Alfred Leslie, the painter who began his career as a second-wave Abstract Expressionist before abandoning the style to paint in a figurative mode, has died, aged 95. His son Anthony confirmed his father’s death to The New York Times. Leslie—who was also a celebrated filmmaker—died as a result of complications from Covid-19.

The son of German immigrants, Leslie was born Alfred Lippitz in 1927, in the Bronx. After high school, he served two years in the Coast Guard in order to become eligible for the GI bill, after which he studied art at New York University, where his professors included the sculptor Tony Smith. Leslie also took courses at the Art Students League and Pratt Institute.

In the early 1950s, he looked poised to take the helm as one of the leading figures in abstract painting. As a 2016 review in Artforum put it, he was at the time considered to be an “[heir] apparent to Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning”. His canvases at the time were De Kooning-esque, with fast-paced brushstrokes and bold planes of colour, and the circle of rising-painters of which he was a member included figures like Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan and Joan Mitchell.

Leslie was a regular at the Cedar Tavern, the hangout of Pollock and De Kooning, and in 1952, at the age of 24, he had his first solo show, organised by the dealer John Bernard Myers and held at Tibor de Nagy gallery. The show’s most prominent work was The Bed-Sheet Painting, a 12-by-16-foot work work that, as Leslie put it in a 2016 interview with Art in America, “had a black, scumbled surface and one leaning white bar in the lower left corner”, adding that he “mounted it unstretched on the main wall, starting at the height of the ceiling, using nails poking through grommets, purposely letting it sag to emphasize its physical presence”.

In 1959, he collaborated with the photographer Robert Frank on the Beat film Pull My Daisy, and successive films included collaborations with the New York School poet Frank O’Hara.

Throughout the 1950s, Leslie was included in a few seminal group shows of the era, including New Talent in 1950, organised by Clement Greenberg and Meyer Schapiro, the Ninth Street Show in 1951 and Sixteen Americans at the Museum of Modern Art in 1959. In 1962, he abruptly shifted away from the abstract mode with which he had found success, producing instead a series of large, greyscale figurative portraits in which the subjects looked directly out at the viewer.

Alfred Leslie in his studio with one of his portraits Courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery

"The adversarial position of 20th-century painting, which was what so attracted me in 1946, seemed to have disappeared by 1960,” Leslie said in a 1985 interview with Art in America. “And it seemed to me that within the framework of figuration there was a way to renew painting." Leslie would continue to paint in the figurative mode for the rest of his life. Honing many of the stylistic and compositional tendencies of these early works would remain his principal focus.

In 1966, much of his work was destroyed in a fire that spread across three Manhattan buildings and killed 12 firefighters. A show of his paintings due to open at the Whitney Museum had to be canceled as a result. “It was like a horror film,” he told The New York Times. “My whole studio burst into flames. I stood on the street and saw my paintings burning through the windows.” The fire—alongside the surprise death of his friend and collaborator Frank O’Haraa few months prior and the escalation of the Vietnam war—influenced Leslie’s work, and for the next 15 years he worked on a series of paintings called The Killing Cycle, with some works containing direct allusions to the dune buggy accident that killed O’Hara.

In 1976, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston organised a mid-career retrospective of Leslie’s work, which traveled to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and further museum shows have followed in the decades since. Today his work is in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum and Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and other institutions.