[ad_1]

Alex Katz, Grey Coat, 1997, oil on canvas.

©ALEX KATZ/VG BILD-KUNST, BONN, 2018/UDO AND ANNETTE BRANDHORST COLLECTION/PHOTO: BAYERISCHE STAATSGEMÄLDESAMMLUNGEN, MUNICH

Alex Katz’s paintings have long been praised for their simplicity—their stripped-down color palettes, their curvaceous forms—but, as one article from the ARTnews archives suggests, his process is anything but minimal. With an exhibition of his paintings on view at the Museum Brandhorst in Munich, we’ve republished below the poet James Schuyler’s essay “Alex Katz Paints a Picture,” which charts the making of one Katz painting. Originally published with photographs of Katz in his studio by Rudolph Burckhardt, the essay is part of ARTnews’s “Artist Paints a Picture” series. Schuyler’s article follows in full below. —Alex Greenberger

“Alex Katz Paints a Picture”

By James Schuyler

February 1962

Alex Katz was born in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, in 1927. His mother was an actress—she studied acting at the Stanislavsky School in Odessa and psychology at the University of Leningrad. During the Revolution she was a gold runner. In America in the ’twenties she was on the Jewish stage, then married and moved to Queens. His father was a gambler until he came to this country and ran a pool hall. He would jump off bridges on a bet.

After high school and a hitch in the Navy, Katz took the three-year course at Cooper Union, where he studied with Harrison and Busa (“Busa clued me into Miró”) and with Gwathmey and Kantor. In the summers he studied at Skowhegan, Maine (where he has since taught), with Henry Varnum Poore. “Poore has lots of sophistication—I guess that was where I first started to paint outdoors, to paint direct. Poore has very sensitive taste.”

On the side, he played basketball for the American Legion.

For the past three years he has taught painting at the Yale art school, commuting once a week from his Manhattan loft. Summers are still spent in Maine, on Slab City Road, near Lincolnville, where he and his family share a small farmhouse (yellow, with a blue door) with the painter Lois Dodd.

“I’d like to slam this one out,” Katz said, and before the sitting was posed or decided on he began mixing a background color in a coffee can. “This is going to be another color; it’s running away from me. I mixed it a way I usually don’t: raw siena, burnt siena and raw umber. I’ve never used raw siena and raw umber before.” And, of course, white.

“This will be sort of an allegory, like the sailor picture [a recent painting, titled Rockaway, of Maxine Groffsky in a lush dress flanked by a sailor and a marine], only more of a straight picture. I’ll transpose things enough to confuse me.”

The next step was spreading newspaper on the orange floor of the living room: his studio on the floor below was too cramped, and too cold for this December afternoon. A good-sized canvas (71 by 50 inches) was set up under a bank of lights, resting against a ladder-back chair from Maine (price, $1.00). Behind him and the surface of the canvas, there was a big painting from last August—the first in the “allegorical” style that showed the painter and his wife Ada and small son striding smiling out of a summer landscape; like the end of a Russian movie when the wheat crop has flourished.

Setting up the pose, Ada Katz took down a box of smart hats (“Is this the one you want Alex?”) and put on her raincoat. Ada says she’s getting tired, a little, of being “the girl in the painting,” whose pictures look more like her than she does.

The writer was dragooned into posing, and so was the photographer, Rudolph Burckhardt (who is also a painter, writer and moviemaker).

He began the painting by drawing in with an orange wash: “This is nice; I think it will be fine.” The layout was bold, all-over and at once. As flood lights for photographing were thrown on the ceiling, Katz said, “Hey, that’s an interesting light to paint by.”

One hazard was one-and-a-half-year-old Vincent. From his mother it was, “Mummy’s got to pose now.” He was quieted with a long brush and corner of his own to work on. As his father speeded up, he speeded up; the canvas also made an effective drum. In five minutes, the figures were roughed in; and Vincent was sitting in the paint.

A mirror was propped on a chair facing the canvas, so I could follow the progress of the painting in it.

Working on the figure profile of his wife, Katz’s brush described short draftsman’s strokes, each usually taking in a bend, a corner of an undulation of cloth; there were no straight strokes or brushing in at this point.

The light background color was used to block out lines from the first sketching, giving, at this early stage, Katz’s characteristic sharp edge to a hat or head. (By now, Vincent was twisting to the Dick Clark television show.)

With a wide brush, the background color was evenly spread on. By now, he had half a dozen brushes in his left hand and, asked about a color, he qualified the formula by saying, “There’s always something on our brush.” As he reached for a fresh tube, I asked, “What’s that?” “White paint. Excelsior!”

“It on you, Ada,” he said, and began painting in her raincoat in a mixture of cadmium yellow, white and a little yellow ocher. For Rudi Burckhardt’s coat, he added a little umber. Wiping in the men’s coats was done without looking at the models.

Ultramarine blue, white and black were used for his wife’s blue sweater, where it showed at the top of her open coat. Most of the “spot” colors came and went, were mixed too fast for me to take them down (Katz’s concentration also induced a reticence about continual quizzing).

While the picture was turned so the first photograph could be taken, Katz said, “This is kind of interesting: I never did three figures on a canvas this size before.” At this point the picture toppled and fell on Vincent. “That almost finished it. It’s a good thing you haven’t got a pointy head.”

Vincent was taken off the scene for his supper while the other two posed. New definitions were brushed in around the washed-in color. Katz works at arm’s length, his wrist having the mobility of pianist’s; it reminded me of the certain flexibility I have observed watching the duo-pianists Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale perform.

A long stretch of detail work followed: lifting a shoulder, defining an ear in its setting of hair, correcting discrepancies between the three posed figures: “Would you move a little closer together? That will save me a lot of repainting.”

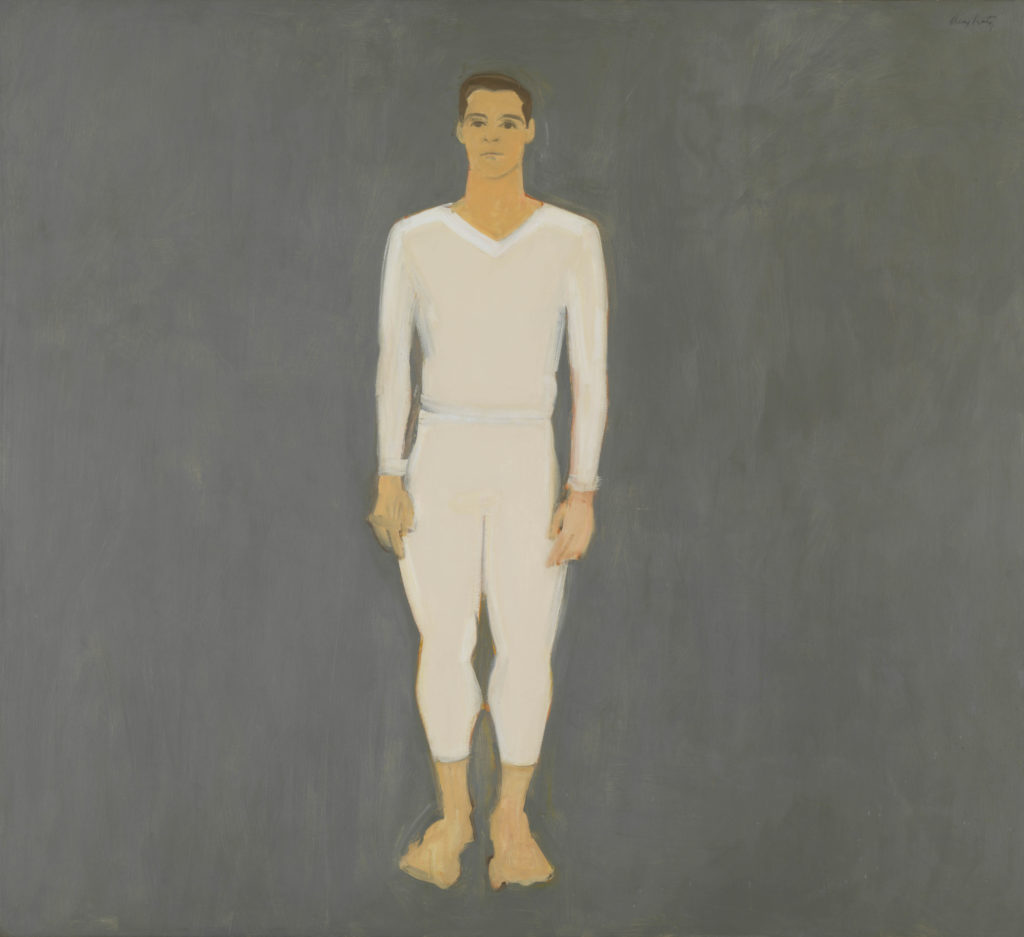

Alex Katz, Paul Taylor, 1959, oil on canvas.

©ALEX KATZ/VG BILD-KUNST, BONN, 2018/UDO AND ANNETTE BRANDHORST COLLECTION/PHOTO: BAYERISCHE STAATSGEMÄLDESAMMLUNGEN, MUNICH

“I think the background may have to go a little darker; I’m using a hell of a lot of lines.” Katz was painting from a standard (encrusted) palette, two coffee cans—one filled with background color and one with turpentine—and the lids of the coffee cans for the raincoat colors. “I’ll see about the background color when I start taking out some of the lines.”

Katz had now reached a point where he could work without his models, who were disposed around in the warm apartment in their raincoats. Vincent had bedtime symptoms with a small crying jag.

After a while: “I’m kind of running down. I think Ada’s raincoat pitched nicely; I guess I can leave the background alone and bring the other colors up to it.” About a popular painter, he said, “His stuff is conceptual. I like habit painting better, so you get some emotional depth.”

Now the models posed individually, so the faces and details could be worked on (“If you try too hard for a likeness, you lose your painting”). Rudy Burckhardt’s hair was first drastically differentiated, according to the highlights, then blocked in, following the fall of a lock onto his forehead. Eyebrows and eyes were quickly put in, the underpainting of the nose and mouth in grey. For the sweater, yellow ocher and cadmium orange: “I guess I’m using a lot of earth colors. I’ve only used them the last couple of years. Before, I used brighter colors.”

“When I use earth colors, I have to dirty them,” Burckhardt said.

“Really? I like them because they’re nice dull colors.”

Work on the face was done with great delicacy and a continuously corrected subtlety.

Vincent made his last appearance in a bedtime skivvy and toting two toothbrushes.

“See the tone of the face is coming out: now I’ve got to see if I can get the pitch of the raincoat color right so I can leave the background alone.”

As Burckhardt’s raincoat progressed, all the lines vanished and the coat took on a flat solidity that emphasized V’s at top and bottom, the natural curve of the left arm and the straight flow down the right to the hand holding a camera.

The painting was turned around again for photographing and assessment. I said, “I didn’t catch it when you put the pink into Rudi’s face.” “It looked kind of chalky so I put some pink in it.”

À propos raw umber: “I wanted to get my colors to have a little more weight so last summer I started using—what do you call it—green earth and colors like that.”

Now it was my turn. I was standing with my weight on my left foot. The heel had begun to ache intolerably and the calf of my leg went to sleep. It was a pleasure to see the smooth brush take years off my life. I tried to remember what it was like to be twenty-four and seeing my first Jackson Pollock; and wondered whatever became of Virginia Bruce.

After another view, Katz said, “God! This looks like something out of Sears, Roebuck!”

Now it was his wife’s turn. “Can’t you make Rudi’s eyes look at me?” she said. “I feel left out.” The orange ribbons on her hat came into being, and from her sleeve a pale hand emerged. After a while she said, “Are you through with me.” “For the time being. I want it to dry a little; it’s all out of whack.” “You know what’s the matter. You started me one way and then you changed my feet.”

“That. I can fix that up. This looks like it’s got a plot: Ada’s husband was hit and Rudi was a witness. Maybe I should put in a jet plane going by.”

Alex Katz, Paul Taylor Dance Company, 1963–64, oil on canvas.

©ALEX KATZ/VG BILD-KUNST, BONN, 2018/BAYERISCHE STAATSGEMÄLDESAMMLUNGEN, MUNICH/UDO AND ANETTE BRANDHORST COLLECTION

I asked him what he meant by allegorical painting.

“Oh God. This was one didn’t end up that way; it’s more straight. Allegorical is like the relation to a story; you know. As soon as I get Ada’s face right this picture will pop. A lot of it is painted or could be. I never made a picture in that kind of space before. Each figure has its own space but there’s none of that Lonely American crap like cheap theater.”

“It’s funny,” he added, “there are these colors I used to use years ago, these kind of blond colors. I hope these have more weight.”

“How can you tell when a painting’s done?”

“When it looks good, I guess. I don’t know—maybe parts look good and parts don’t look good and maybe after a while the whole thing looks good. In this one I don’t have to worry about the schmaltz of the paint—thin paint—it seems nice and solid and fluid the way it moves across the picture.

“Tomorrow I’ll be looking at this cold. Then I see if there’s anything I can fix right away. After that a lot of time has to go by; you can’t do anything to it.”

Katz had been painting from four until eight-thirty. At ten o’clock, after dinner (delicious), he said to his wife, “I need a razor blade. I have to scrape your face out.” As he scraped it down, he said, “It looks more like you already,” and the solidly filled profile of her features did. He began wiping with a rag, blending the brown of hair into a light shadow on the right side of her face. “Three-quarter view now, kid.” His most experienced model knew just what he meant. Her features came in with a startling resemblance, including the cadmium red of her lipstick. The touches now were brief and scattered: a light line to define the hat brim, a wipe of the ground that sharpened the profile of hat and hair on the right.

Then I posed again, and acquired a quarter inch of sideburn. A line up the white area in my hands turned it into a notebook; two strokes made the pen and its blue cap.

Touching and retouching: how boring and fascinating the processes of art are. Ada Katz’s cheek ran flatly down into her neck, without definition. “Tomorrow I’ll be able to see what it looks like in daylight.” The expression in her eyes was sharpened.

At midnight, the painting was, perhaps, done.

“I’m going to call it quits,” Katz said.

[ad_2]

Source link