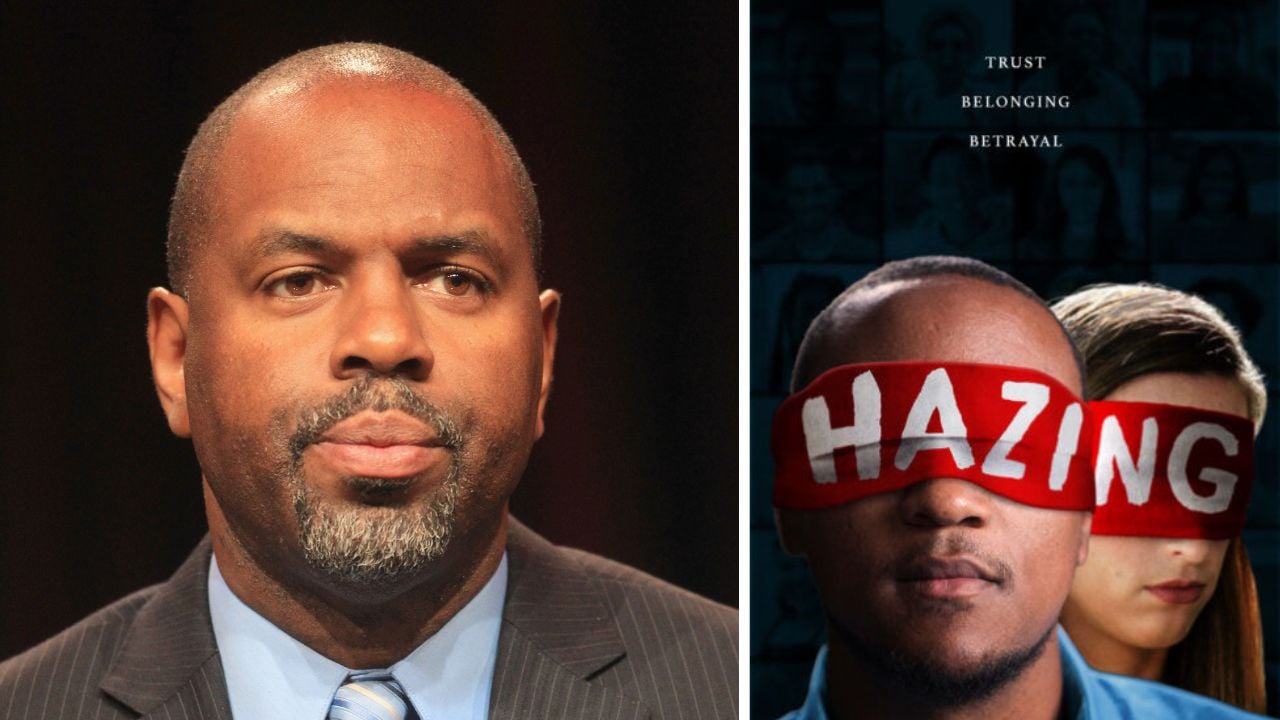

Three years after his documentary “Hazing,” and in the wake of Caleb Wilson’s death, Byron Hurt discusses why hazing still happens.

In 1894, the first anti-hazing law in the United States was enacted in New York after a group of students at Cornell University filled a freshman banquet hall with chlorine gas, killing one staff member and injuring several others.

Nearly a century and a half later, 43 more states and the District of Columbia have passed their own versions of anti-hazing laws. Beyond state legislatures, wide swaths of organizations, including sororities and fraternities, have instituted their own anti-hazing policies.

Yet hazing, ranging from petty tasks to humiliating pranks to acts of great peril in order to gain acceptance into a group, still occurs on campuses, within law firms, at private clubs, and in exclusive organizations all over the country.

After Caleb Wilson, a 20-year-old junior mechanical engineering student at Southern University and A&M College, died in February after he allegedly participated in a fraternity hazing ritual of a fraternity that does not condone hazing, many are left wondering: Why does hazing still happen?

Byron Hurt, the award-winning director of the 2022 documentary “Hazing,” told the Grio that hazing has a stronghold in culture in large part because of “tradition.”

“There is this belief that in order for a newcomer into an organization to be seen as credible, and as valuable, and worthy, they have to go through some process that is difficult, challenging, arduous, that other people before them have experienced,” Hurt said, adding, “There is an overvalue of the idea of tradition, the sense that ‘This is what we do, this is what we’ve always done, and this is how we measure good, credible members versus members who are not good or who have no credibility.’”

Hurt said this sense of tradition may have created for some the mindset that “‘You have to go through this process in order for you to gain my respect, in order for me to be able to accept you into my group.’”

Hurt, whose film “Hazing” sheds light on the ongoing taboo practice across many different demographics, knows firsthand what this kind of groupthink mentality can feel like. A member of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. (though not speaking to theGrio on behalf of the organization or as a member), Hurt has been on both sides of hazing. He now uses his platform to spread awareness and to bring an end to the tradition.

Part of ending hazing may lie in understanding it can be as nuanced as the legions of organizations secretly keeping the practice alive. Hurt said, in particular, with Black organizations, there’s a very complicated legacy with violence and oppression some can operate under.

“There are more layers to the culture of hazing than there are in white organizations. White organizations, they don’t have the same cultural background and cultural history that we have as Black people in America,” Hurt continued. “They haven’t experienced a level of oppression, pain, trauma, victimization, violence, and so those things, those traumas, get passed down from generation to generation.”

Hurt said elements of white supremacy, internalized victimization, and internalized oppression can end up “playing out in some of our Black exclusive groups.”

Whether or not a more rigorous initiation process makes for a more dedicated member of an organization or club remains to be seen. Hurt noted that there are plenty of examples of members who didn’t go through a difficult process and who went on to become some of the most dedicated and active in the group. Meanwhile, there are also plenty of examples of the opposite: members who were put through the wringer to join and then turned out to be less than committed.

“There is a good case to be made about activities in which people have to earn their way into the organization, but those activities don’t have to be violent at all,” Hurt said, adding that instead, activities should center around capitalizing “on the talents and the gifts that individuals are bringing” to the organization.

This could look like having potential members take on charity initiatives, community-building projects, and beyond.

“Because it’s not just hazing,” he said. “It’s violence that is being inflicted upon another person. In this case, someone’s child, someone’s cousin or loved one, or bandmate, classmate, and so when you look at it from that perspective, then you have to ask questions, ‘Well, why does such violence exist?’”

Since Wilson’s death after he was allegedly punched several times in the chest while in a warehouse off campus, Hurt said many have reached out urging him to continue spreading the word to end hazing.

“I think people are more receptive right now to hearing anti-hazing messages like the one in my film,” he noted.

When asked what he thinks it will take to end hazing, Hurt said, “It’s going to be really difficult to completely end hazing.”

“You’re dealing with young people whose minds are not fully formed … who don’t fully understand the risks that they are taking with someone’s life and including their own life,” he continued.

When it comes to victims of hazing, Hurt said stepping away from an organization that does it is also an option. “There’s something about honoring who you are as a human being that supersedes what other people think about you,” he said.

However, the obligation ultimately rests on the perpetrators and would-be perpetrators to stop.

“We have to stop doing that to people,” Hurt said. “That’s where the focus should be.”

More About:HBCU Lifestyle

Weekly New Episodes

Stream Now