[ad_1]

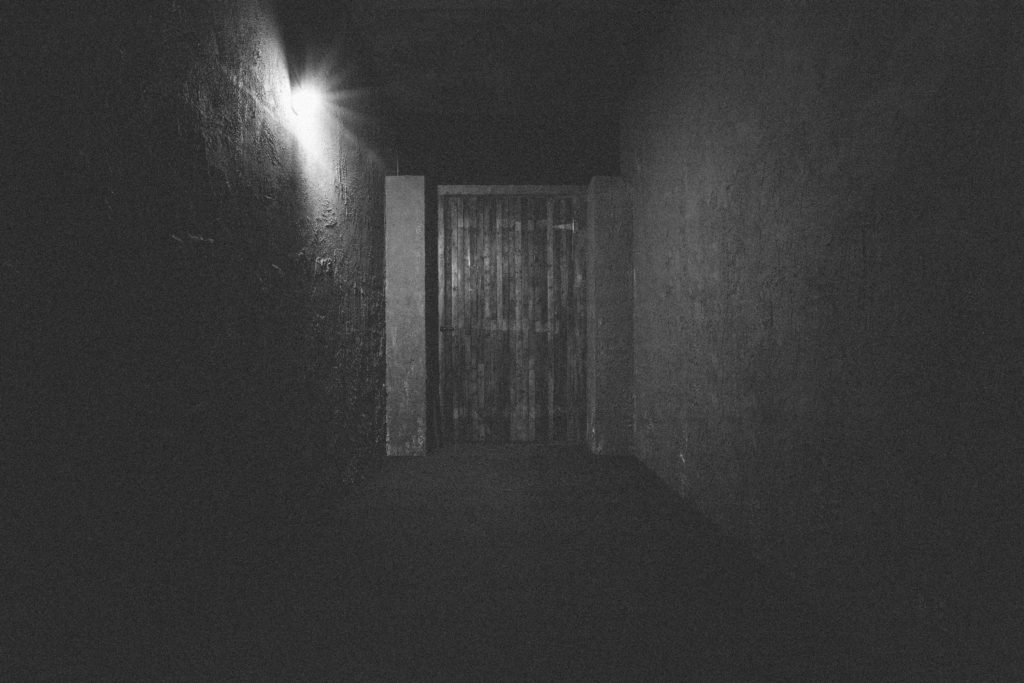

Installation view of “Adam Gordon: The Grey Room” at the Power Station in Dallas, 2018.

COURTESY THE POWER STATION

‘When a door opens into someone’s house and you get a waft of that air, all of the sudden it’s extremely personal,” the artist Adam Gordon said, of entering a stranger’s home. “It’s almost shockingly intimate because of the smell, the tone, and the light.”

It was a breezy afternoon in Dallas last month, and Gordon, who is 32 and trim, with thick, short black hair, was sitting at a picnic table outside the Power Station, a handsome three-story brick building in a warehouse district where he had opened a show the night before. He was explaining how, while in graduate school at Yale University, he once drove around Connecticut knocking on people’s doors.

“I would just ask to come inside,” Gordon said, narrating how he would tell whoever answered that he was from the nearby school and working on a project. “Obviously it’s very awkward if you don’t have a plan, which I didn’t,” he continued, nevertheless sounding quite confident. “I would knock and just make something up. So I’m just knocking on doors and creating the most awkward situation possible—but finally I knocked on someone’s door and I knew that there was something here.”

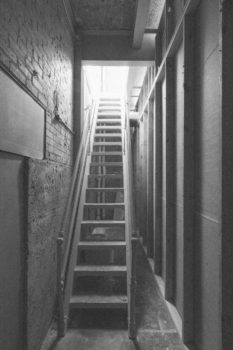

The Power Station in Dallas.

ANDREW RUSSETH/ARTNEWS

A man he thought to be in his 30s greeted him, and he could see the man’s mother, in a wheelchair, in the background. “I knew that I wanted to talk to these people more,” he said. “I don’t know why, but eventually they let me in. To make a long story short, I ended up having students from Yale in the art department go in small carpool groups to hang out with this guy and his mother. The father in the family had recently died, and this young man, who was in college, was essentially taking care of his mother, who was quite ill. I could tell that they wanted company.”

Gordon’s work thrives on such unlikely crossings of social boundaries and delving into unseen, often psychologically charged spaces—whether he hunts them down and finds a way inside or creates them himself. Last year, he installed a mysterious, vaguely menacing room with a rust-stained floor and a glass wall in the booth of his New York gallery, Chapter NY, at Art Basel Miami Beach last year. In 2015, one of his contributions to a group show at Derek Eller in Manhattan involved having a makeup artist age a woman by a decade whom he then instructed to walk along particular streets in Hell’s Kitchen. “I told her if anyone interacted with her to completely ignore them as if she’s in some other dimension,” he said. “In other words, she’s just a living sculpture walking on these particular streets, so she has no connection to anything.”

Taking the form of hyper-realistic paintings, uncanny installations, bizarre photographs, or uncategorizable situations, Gordon’s art is one of uncomfortable intimacies, and it’s among the most interesting, unusual, and sometimes discomfiting work being created right now.

“The Grey Room,” his exhibition at the Power Station in Dallas, also begins with the opening of a door—a heavy, metal one accessible from the first landing of an outdoor staircase that runs up the side of the building. A sign next to the door states, in bright red letters, that those who enter do so at their own risk, relinquishing their right to sue “for any injury or death to any person.” (The show, which runs through September 14, is open only Friday afternoons and by appointment, for one visitor at a time.)

Installation view of “Adam Gordon: The Grey Room” at the Power Station in Dallas, 2018.

COURTESY THE POWER STATION

Before meeting up with Gordon, I opened the door and found a completely empty room, beautifully lit with low natural light. There was no one around, but there was an unidentifiable smell—sharp but not entirely off-putting—that imparted a certain level of anxiety. It felt like someone had just been in there, and I sensed I was being watched. A staircase led down to a pitch-black space, with a tiny light hovering high in the distance. Keeping my hand on the rough, craggy wall for balance, I inched along in the claustrophobic darkness, passing over a metal grate and almost wiping out on a step. The room seemed to be huge, and I felt achingly alone.

It took at least five minutes for my eyes to adjust, and when they did I could barely make out two thin totems in the room, standing like ghostly sentinels. A giant door stood at the far end and, eventually groping around on it, I found a latch and pulled. It glided open, creaking like a frightening door in a horror film. The next room—small and also dimly lit—had a semi-translucent wall behind which some black form was lurking. Still another room was a kind of dilapidated version of the upper floor but rundown and partially cordoned off. A door to the outside was there, and it was a relief to pass through it, back into fresh air.

The time when I was supposed to meet Gordon had arrived, but there was no one in sight. Given that I had never come across an interview with him before, it occurred to me that he would perhaps not be showing up, having maybe decided that his eerie show could stand in for him, providing all I needed to know.

Installation view of “Adam Gordon: The Grey Room” at the Power Station in Dallas, 2018.

COURTESY THE POWER STATION

But it turned out that he was simply elsewhere in the building, and when we soon found each other, he was wearing a black T-shirt and black pants. He seemed serious but friendly, radiating a kind of steely charisma. Since so much of his art—creepily empty spaces, forced interactions—involves withholding information or engaging an element of surprise, I admitted that I had not necessarily been expecting him to be willing to do an interview. “This might be the only one,” he said. “I don’t think I’ll do many, that’s for sure.”

Discussing how the show came together, Gordon said he’s not the type to retreat into his studio and work. Instead, he spent a lot of time driving around Dallas. “The environment around here—industrial office parks and certain kinds of just very isolated areas out in the suburbs—had an effect on me. I wanted to bring some of that energy, a residue of those isolated spaces, into this work.

“I was thinking about the building as a kind of house,” he continued, noting that he wrote a poem that guided his approach:

Months lengthen into years.

In these rooms families will emerge and grow.

On the upper floors we may have a boring conversation.

Dim light moves across the walls as the days turn.

In the basement there is a large lady, constantly throwing children out into the world, and I stand with my brothers and sisters who are all in various corners of her stone room.

He is more interested in “particular atmospheric conditions” than narrative, he said, and is an “obsessive list maker,” writing out “exactly what needs to happens” in order to create the effects he imagines. Philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 tome The Poetics of Space was a key inspiration. “I’m very much simplifying it, but a takeaway from that book was that a traditional house is set up like the unconscious,” he said. “I was thinking about the exhibition in a similar way.” One first enters a home into a place where you might “have a friendly conversation, at least a civil conversation, with neighbors or friends. And then as you descend, especially into the basement, that’s representative of the id in a certain way. In the basement, the conversation you would have had upstairs in a light-filled space starts degrading. Suddenly there is a certain violence, a certain sexual component. That’s the way I think of the lower layers, especially the dungeon area”—that dread-inducing black room in the Power Station.

The view through the glass wall into Adam Gordon’s piece in the booth of Chapter NY at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2017.

ANDREW RUSSETH/ARTNEWS

It would be tempting to lump Gordon’s work in with the environments of figures like Mike Nelson, Christoph Büchel, and Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe, but while those individuals traffic in specific, seamless spectacles, Gordon’s alterations resist any easy reference points and never quite obliterate the fact that they exist in a gallery. They’re minimal but potently condensed. He kills the lights, meticulously paints the walls, and in the case of the Dallas show, imbues each room with a specific scent, dispersed through hidden diffusers or by painting odiferous oil onto walls or bits of plaster. (The scents come from a collaborator in New York who conjures what the artist describes. “I can say that I need something that’s a little bit sweet but rotten but it’s musty. It’s like dead air. It hasn’t moved.” Gordon said.)

He names the spaces he creates. The empty top floor in Dallas is The Grey Room. The space below the stairs is Dead Maiden. And the final location, just before the exit, is Hardcore—“a doppelganger of the first one, but more of like a decrepit cousin.” (As certain music aficionados might deduce, Gordon has been involved in the black metal and power electronics scenes for years.)

The spaces are site-specific, but “I do think it’s possible in certain circumstances to extract a room and place it somewhere else,” Gordon said. He has been carefully measuring and documenting the spaces he’s used, noting materials and scents, so that he can one day remake them. “I feel like the rooms are living here, because they were created for this space,” he said. “If you divorce rooms, there’s a death to the work in a way, but it’s an interesting idea for me that a room could lose its original presence but still have an afterlife.”

Installation view of “Adam Gordon: tiernan” at Chapter NY, 2016.

COURTESY CHAPTER NY

Given his meticulousness, it’s not a shock to discover that Gordon’s outré practice is grounded in heavy technical training. After growing up in Minneapolis, he attended the Lyme College of Fine Arts in Old Lyme, Connecticut, which focuses on traditional art techniques—oil painting, casting, proportions. “The whole nine yards of a traditional art education in France in the 18th century,” Gordon said. “That was something I was very obsessed with at that time.”

Coming across the sharp-edged work of Lee Lozano—whose pieces involved endeavors like refusing to speak to women for a stretch or smoking weed for a month straight—led to a change in his work. “Who is this woman?” he recalled thinking. “I was fascinated because here I was, learning anatomy and blah-blah-blah . . .” He realized that “art could be experience itself. Art could be ephemeral. Art could be something that you essentially create and make something happen and no one sees it.” Like, for instance, a made-up woman wandering the streets of Manhattan.

Gordon has also embedded photographs and paintings behind drywall in some of his shows—things that only he has known were there but permeated the show in some ineffable way. He aims to make exhibitions in which “not everything has to be so epidermal,” that can have hidden “subliminal” components.

As it happens, Gordon reminded me, Lozano lived the last two decades of her life in Dallas. She moved in with her parents in 1982, more than ten years after she began Dropout Piece (ca. 1970), for which she declined to participate in the art world any longer. When she died of cancer in 1999, at the age of 68, she was buried in the city in an unmarked grave.

“I’ve been driving around doing errands and enjoying the thought of wondering if she’s been here,” Gordon said. “Maybe she went down this road at some point. I feel like she’s in this work because I was constantly thinking about her and the sheer intensity of her practice.”

Installation view of “Adam Gordon: The Grey Room” at the Power Station in Dallas, 2018.

COURTESY THE POWER STATION

There are moments when Gordon can sound controlling and manipulative—charming his way into people’s homes, sending individuals on strange excursions that no one will ever witness, harboring away works that only he knows are present. But I had the sense of someone with a rare sensitivity to the goings-on of the world and a desire to make himself radically vulnerable, even if it means shrugging off social niceties. Gordon throws himself into his work—or it might be more accurate to say that he lets it overtake him. “I’m led around,” he said at one point. “I have intention, but the everyday banality of shit that happens can be very influential on me all of the sudden.”

As we neared the end of our talk, Gordon said, “The space I exist in is very porous, and my work and my life are becoming one thing.”

It looked like it was about to rain at any moment, and the breeze was starting to pick up. “My perfect scenario is—this is a good day, today,” he said. “Overcast. You’ve got the wind and you come here alone and let yourself in. You should be able to make an appointment and spend as much time as you want. You could spend all day. Maybe you don’t come out—maybe you fall somewhere, maybe you get locked in and can’t get yourself out.”

Gordon knows those sensations. “I don’t feel like I can get out,” he said. “I’m stuck in these rooms. They just come with me.”

[ad_2]

Source link