[ad_1]

Willem de Kooning’s Untitled XXII, 1977, sold for $30.1 million at Sotheby’s New York.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

Buoyed by heavy bidding from Asia for the evening’s top four entries, Sotheby’s contemporary sale on Thursday night racked up a rock-solid $270.7 million for the 46 lots sold. Only four of the 50 lots offered failed to sell, for a svelte buy-in rate by lot of eight percent. The tally, including fees, hit near the high end of pre-sale expectations of $205.7 to $288.3 million. (The hammer total before fees was $230 million.)

Still, the sale lagged behind last November’s $362.5 million total, for the 63 lots that sold one year ago.

Four artist records were set. All but one of the works sold went for more than $1 million; six surpassed $10 million; and three exceeded $20 million. A single lot, Piero Manzoni’s wrinkled canvas abstraction Achrome (1959), estimated at $8 million to $12 million, was withdrawn at the 11th hour.

Financing-wise, 23 works were backed by so-called irrevocable bids from third parties in partnership with Sotheby’s, and three were standalone house guarantees.

(All prices reported include the hammer price plus the buyer’s premium for each lot sold, calculated at 25 percent of the hammer price up to and including $400,000, 20 percent of any amount in excess of that up to and including $4 million, and 13.9 percent for any sum beyond that. With such figures, Sotheby’s has the highest buyer’s premium in the field.)

The evening action opened with a bang as the first lot, Charles White’s charcoal work on illustration board Ye Shall Inherit the Earth (1953), a moving depiction of a straw-hatted woman cradling an infant who looks out shyly at the new world, made a record $1.7 million (est. $500,000-$700,000). The work included in the artist’s recent traveling retrospective was White’s evening auction debut at Sotheby’s, 24 hours after another work of his set a record at Christie’s.

The second lot, Kerry James Marshall’s playfully sexy Small Pin-Up (Lens Flare) from 2013, in acrylic on PVC, demonstrated the artist’s growing market might as it hit $5.5 million (est. $2.5 million-$3.5 million). Los Angeles-based dealer Stavros Merjos was the underbidder on the work by Marshall, who was a student of White at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in the late 1970s (as was David Hammons in the previous decade).

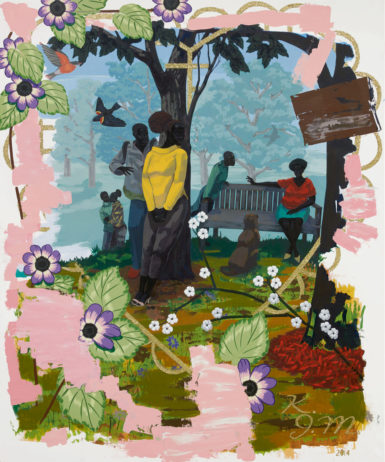

Kerry James Marshall’s Vignette 19, 2014, sold for $18.5 million at Sotheby’s New York.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

A second Marshall later in the sale, Vignette 19 from 2014—depicting a utopian setting with a trio of African-American couples and considerably larger at nearly 6 by 5 feet—soared to $18.5 million (est. $6.5 million-$7.5 million).

Ed Ruscha was back in the mix when—though far from the record heights of Hurting the Word Radio #2 that sold for a $52.5 million record at Christie’s on Wednesday—his 1974 text painting She Gets Angry at Him from the collection of fashion icon Marc Jacobs first failed to sell at $1.9 million (est. $2 million-$3 million), only to come back and be re-offered at the end of the long evening and selling for $1.7 million. The painting, which last sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2014 for $2.11 million, carried a house guarantee, and only a seasoned auction observer could surmise what the re-offer involved, one tied to a so-called global reserve when more than one lot is being offered from a consignor.

Two other entries from Jacobs’s collection—another Ruscha and a 2006 work by John Currin, Helena, which sold for $1.16 million to New York dealer Jonathan Boos (est. $500,000-$700,000)—offered some wiggle room around the under-performing She Gets Angry at Him. And a Sotheby’s executive said the re-offer had to do with a botched phone line. Go figure.

New York art stars from different eras were represented, with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Famous Negro Athletes, a stellar 1981 oilstick-on-paper from the estate of the late writer and downtown scene-maker Glenn O’Brien, going to a telephone bidder for $3.02 million (est. $2.5 million-$3.5 million) and Richard Prince’s pulp-fiction-enhanced Park Avenue Nurse (2002) selling to another phone bidder for $6.19 million (est. $5 million-$7 million).

A second Basquiat oilstick-on-paper, Brown Eggs—also from 1981 and featuring a ferocious-looking disembodied head floating over the inscribed title and a scrambled line-up of colored eggs—made a whopping and estimate-busting $5.39 million (est. $2.5 million-$3.5 million). It last sold at Sotheby’s London in July 2015 for £1.18 million (around $1.84 million).

Another generational star of more recent vintage figured in the evening when Julie Mehretu’s chaotically controlled and sprawling 2001 composition Rise of the New Suprematists, measuring 95 by 118 inches, sold to a bidder on the phone for $4.82 million (est. $3.5 million-$4.5 million). It was exhibited in the 2004 Whitney Biennial.

In like fashion, with its submerged references to architecture and urban planning, Mark Bradford’s mixed-media collage on canvas Spinning Man (2007) leaves the impression of a densely packed city seen from a great height—and sold for $5.85 million (est. $5 million-$7 million).

Though absent of figures, David Hockney’s evocative 1964 composition in acrylic on canvas Picture of a Hollywood Swimming Pool—which telegraphs the sunny and sumptuous lifestyle that so enamored the artist during his first visit to Los Angeles in 1963—sold for $7.21 million (est. $6 million-$8 million). It last sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2001 for $610,700.

The evening also featured a number of Abstract Expressionist works, led by Willem de Kooning’s juicy 70-by-80-inch oil on canvas Untitled XXII—a work from 1977 that last appeared in Mnuchin Gallery’s “Chamberlain/de Kooning” exhibition in 2016. The de Kooning sold to another telephone bidder for the top lot price of $30.1 million (est. $25 million-$35 million.) It came backed by an irrevocable bid, and art advisor Judith Hess was the underbidder. Similar works by de Kooning are cloistered in museums including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Guggenheim, and the Stedelijk in Amsterdam.

The painting was consigned by noted gallerist and razor-sharp octogenarian Robert Mnuchin, who was present in the salesroom. As he headed toward the elevator bank and was intercepted by this reporter with a question about the price, he said, “I don’t want to comment on that painting, but there was lots of energy in the room—and more energy than we’ve seen in some time.” He wasn’t kidding.

In the parade of iconic names and painterly gestures, Clyfford Still’s fresh-to-market abstraction PH-399 (1946) sold to a telephone bidder for $24.3 million after a mind-numbing 15-minute bidding battle (est. $12 million-$18 million). On a smaller scale, a power-packed Jackson Pollock drawing, executed in black and colored inks in 1944, sold for $4.22 million (est. $1.5 million-$2 million).

Lee Krasner’s Sun Woman I, 1957, sold for $7.38 million at Sotheby’s New York.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

Though long in Pollock’s shadow as his dutiful wife and legacy protector, Lee Krasner had a star turn when her superlative Sun Woman I—painted in 1957, a year after her husband’s death, and part of an acclaimed “Earth Green” series that was first exhibited at the Martha Jackson Gallery in 1958—sold to another telephone bidder for $7.38 million (est. $6 million-$8 million). It last sold at auction at Sotheby’s New York in November 2011 for $782,500.

Luminous in calibrated shades of orange, red, blue, and yellow, Mark Rothko’s 64-by-35-inch Blue Over Red (1953)—listed in David Anfam’s authoritative catalogue raisonné—brought in $26.5 million (est. $25 million-$35 million). Significantly, 10 of the 16 paintings that Rothko made that same year are held in museum collections, including the Whitney, the Guggenheim Bilbao, and the Met—so one might surmise that this rather underwhelming example was still a good bet. Sotheby’s secured a late irrevocable bid for the painting, which last sold at Christie’s New York in November 2005 for $5.6 million.

An undisputed Abstract-Expressionist standout was Norman Lewis’s flickering and richly hued composition Ritual (1962), which sold to Gabriel Catone of New York art advisory Ruth Catone for an artist record of $2.78 million (est. $700,000-$1 million). It was included in a traveling Lewis retrospective than ran from 2015 to 2017, and it was also a debut for Lewis in a Sotheby’s evening auction.

You might say Brice Marden was an inheritor of the Ab Ex legacy, and his Number 2 (1983-84)—an oil on canvas in 12 parts measuring 84 by 109 inches—counts as a fine specimen of his important series of “post-and-lintel construction” paintings. It sold to a telephone bidder for a record $10.9 million (est. $10 million-$15 million) and came backed by an irrevocable bid. It broke the previous mark set by The Attended (1996-99), which sold at Sotheby’s New York in November 2013 for $10.9 million. That’s right: a $3,000 difference—but every little bit helps.

In an auction decidedly thin in Pop art offerings, with not a single Warhol in sight, Roy Lichtenstein’s German-Expressionist-styled portrait Dr. Waldmann (1979), made $5.96 million (est. $4 million-$6 million).

Francis Bacon’s Pope, 1958, sold for $6.64 million at Sotheby’s New York.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

Deaccessioned by the Brooklyn Museum to support the institution’s collection, Francis Bacon’s sketchy and travel-worn Pope from circa 1958 scraped by at $6.64 million (est. $6 million-$8 million). Curiously, three Bacon iterations of Pope paintings have sold for more than $40 million at auction, the highest being $52.6 million for Study from Innocent X from 1962, which sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2007.

And though Sotheby’s accurately cited tonight’s Pope as listed in the Bacon catalogue raisonné by Martin Harrison, the painting was scorned by Bacon himself, who reportedly gave it away with other studio works to a friend with the intention of using the canvases for new work. Instead, the friend sold them—and one wound up in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection some 40 years ago. Bacon wrote a letter to the museum complaining about it, and if the artist was still around, it’s doubtful the painting would have made it to auction. (It also carried an irrevocable bid.)

After the sale reached its end, the takeaway was clearly expressed by Madison Avenue dealer Emmanuel Di Donna, who observed, “It was a very solid sale. It was slow, considered bidding—but quite deep.”

The market lives on.

[ad_2]

Source link