[ad_1]

This story was originally published by ProPublica.

PONTIAC, Mich. — One afternoon in mid-June, Charisse* drove up to the checkpoint at the Children’s Village juvenile detention center in suburban Detroit, desperate to be near her daughter. It had been a month since she had last seen her, when a judge found the girl had violated probation and sent her to the facility during the pandemic.

The girl, Grace, hadn’t broken the law again. The 15-year-old wasn’t in trouble for fighting with her mother or stealing, the issues that had gotten her placed on probation in the first place.

She was incarcerated in May for violating her probation by not completing her online coursework when her school in Beverly Hills switched to remote learning.

Because of the confidentiality of juvenile court cases, it’s impossible to determine how unusual Grace’s situation is. But attorneys and advocates in Michigan and elsewhere say they are unaware of any other case involving the detention of a child for failing to meet academic requirements after schools closed to help stop the spread of COVID-19.

The decision, they say, flies in the face of recommendations from the legal and education communities that have urged leniency and a prioritization of children’s health and safety amid the crisis. The case may also reflect, some experts and Grace’s mother believe, systemic racial bias. Grace is Black in a predominantly white community and in a county where a disproportionate percentage of Black youth are involved with the juvenile justice system.

Across the country, teachers, parents and students have struggled with the upheaval caused by monthslong school closures. School districts have documented tens of thousands of students who failed to log in or complete their schoolwork: 15,000 high school students in Los Angeles, one-third of the students in Minneapolis Public Schools and about a quarter of Chicago Public Schools students.

Students with special needs are especially vulnerable without the face-to-face guidance from teachers, social workers and others. Grace, who has ADHD, said she felt unmotivated and overwhelmed when online learning began April 15, about a month after schools closed. Without much live instruction or structure, she got easily distracted and had difficulty keeping herself on track, she said.

“Who can even be a good student right now?” said Ricky Watson Jr., executive director of the National Juvenile Justice Network. “Unless there is an urgent need, I don’t understand why you would be sending a kid to any facility right now and taking them away from their families with all that we are dealing with right now.”

In many places, juvenile courts have attempted to keep children out of detention except in the most serious cases, and they have worked to release those who were already there, experts say. A survey of juvenile justice agencies in 30 states found that the number of youths in secure detention fell by 24% in March, largely due to a steep decline in placements.

In Michigan, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer issued an executive order in March that temporarily suspended the confinement of juveniles who violate probation unless directed by a court order and encouraged eliminating any form of detention or residential placement unless a young person posed a “substantial and immediate safety risk to others.” Acting on Whitmer’s order, which was extended until late May, the Michigan Supreme Court told juvenile court judges to determine which juveniles could be returned home.

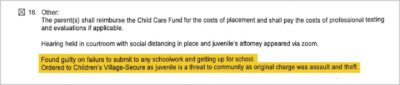

Judge Mary Ellen Brennan, the presiding judge of the Oakland County Family Court Division, declined through a court administrator to comment on Grace’s case. In her ruling, she found Grace “guilty on failure to submit to any schoolwork and getting up for school” and called Grace a “threat to (the) community,” citing the assault and theft charges that led to her probation.

“She hasn’t fulfilled the expectation with regard to school performance,” Brennan said as she sentenced Grace. “I told her she was on thin ice and I told her that I was going to hold her to the letter, to the order, of the probation.”

That June afternoon, a month after the sentencing, Charisse left Children’s Village without seeing Grace, but she did pick up a shopping bag of clothes and toiletries she had delivered days earlier. She said officials had rejected them because they violated facility rules: underwear that wasn’t briefs; face wipes that contained alcohol; a pair of jeans deemed too tight.

Charisse counts each day they’re apart, and that was day No. 33. Another month has since passed, and there could still be months to go before they are at home together again.

Driving home, Charisse had to pull over soon after she turned onto the road leading away from the complex. She sat in a parking lot, sobbing.

“It just doesn’t make any sense,” she said. She shook her head as tears dampened the disposable blue face mask pulled down to her chin.

“Every day I go to bed thinking, and wake up thinking, ‘How is this a better situation for her?’”

It has always been just the two of them, Charisse and Grace.

Told by doctors that she would be unable to have children, Charisse, a consultant to nonprofit organizations, was shocked when she became pregnant at 44. She has raised Grace on her own after the girl’s father did not want to be involved, she said.

They did everything together: winter sports throughout Michigan, rounds of golf, going to the opera, singing to Tony Bennett on road trips. They even appeared in a “Pure Michigan” tourism ad. As a child, Grace wanted so much to be like her mother that she asked to be called Charisse No. 2.

When Grace hit her preteen years, however, their relationship became rocky. They argued about Grace keeping her room clean and doing schoolwork and regularly battled over her use of the phone, social media and other technology.

By the time Grace turned 13, the arguments had escalated to the point that Charisse turned to the police for help several times when Grace yelled at or pushed her. She said she didn’t know about other social services to call instead. In one incident, they argued over Grace taking her mother’s iPhone charger; when police arrived, they discovered she had taken an iPad from her middle school without permission. At her mother’s request, Grace entered a court diversion program in 2018 for “incorrigibility” and agreed to participate in counseling and not use electronic devices. She was released from the program early, her mother said.

While there was periodic family conflict, Grace has always had strong friendships and is active in her school and community, her mother said. She has helped run programs at church, played saxophone in the school band and composed music, and regularly participated in service projects.

The incident that led to her current situation happened Nov. 6, when someone called the police after hearing Charisse crying “Help me!” and honking her car’s horn. Grace, upset she couldn’t go to a friend’s house, had reached inside the car to try to get her mother’s phone and had bitten her mother’s finger and pulled her hair, according to the police report.

Police released Grace to a family friend to let the two cool down and referred the case to Oakland County court, where an assault charge was filed against her.

Weeks later, she picked up another charge, for larceny, after she was caught on surveillance video stealing another student’s cellphone from a school locker room.

“After I was caught, I felt instant remorse and guilt. I wanted to take back everything I had done,” Grace wrote in a statement to police. She said she had questioned herself even as she took the phone but wanted one after her mother took hers away.

The other student’s mother, who declined to comment for this story, told police she wanted to press charges, although the phone had been returned to her son soon after Grace took it. “My sincere hope is that any punitive action taken in this case be grounded in the goal of providing this student with opportunities for growth, change and future success,” she wrote in a statement to police.

In the months following the two incidents, Grace and her mother participated in individual and family therapy and Grace stayed out of trouble.

Charisse told a court caseworker assigned to the case that other than being irritable and getting “cabin fever” from being shut at home during the pandemic, “nothing significant” had taken place between the mother and daughter. There was no police contact after the November incidents, records show.

The April 21 juvenile court hearing on the larceny and assault charges against Grace was conducted via Zoom since the courts had shut down, with everyone calling in from their homes. Grace connected from her bedroom, her mother from their living room.

It had the familiar awkwardness of many online meetings: dropped audio; a dog barking in the background; participants swivelling in their chairs; the prosecutor losing his connection. (This hearing and others in the case were recorded, and a ProPublica reporter watched them at the Oakland County courthouse last month.)

Ashley Bishop, a youth and family caseworker for the court, told the judge she thought Grace would be best served by getting mental health and anger management treatment in a residential facility. The prosecutor, Justin Chmielewski, said he agreed. Grace’s court-appointed attorney, Elliot Parnes, said little but asked that she be given probation because she had committed no new offenses and because of the risk of COVID-19 in congregate facilities.

Parnes and Bishop declined to comment for this story and Chmielewski did not respond to calls.

Throughout the hearing, Grace took her glasses off to brush away tears and wiped her nose with her sleeve. She shook her head, which the judge later criticized as a sign of disagreement but which Grace told ProPublica signaled her disappointment in her past behavior. She raised her hand a couple times and asked, in a small voice, “Can I just say something please?”

“My mom and I do get into a lot of arguments, but with each one I learn something and try to analyze why it happened,” she said. “My mom and I are working each day to better ourselves and our relationship, and I think that the removal from my home would be an intrusion on our progress.”

Brennan admonished Grace for the fights with her mother, her thefts at school and behaving in a way that required police to come to their home. “Police,” she said. “Most people go through their entire youth without having the cops have to come to their house because they can’t get themselves together.”

But, citing the pandemic, Brennan decided not to remove Grace from her home and instead sentenced her to “intensive probation.” The terms of the probation included a GPS tether, regular check-ins with a court caseworker, counseling, no phone and the use of the school laptop for educational purposes only. Grace also was required to do her schoolwork.

“I hope that she upholds her end of the bargain,” Brennan said at the end of the hearing.

Schools across the country weren’t prepared for the abrupt turn to remote learning. Grace’s school, Groves High School, in one of the most well-regarded districts in the state, was no different.

In mid-March, thinking the closures might last for only a month, the district initially offered optional online activities and then recessed for an already-scheduled weeklong spring break. Soon after, Whitmer announced that schools would end face-to-face instruction for the rest of the year. The Birmingham Public Schools superintendent asked families for patience as schools moved to an online curriculum in mid-April and promised flexibility in their support. Officials said student work would be evaluated as credit/no-credit.

The initial days of remote school coincided with the start of Grace’s probation. Charisse was concerned that her daughter, who was a high school sophomore and had nearly perfect attendance, would have trouble without in-person support from teachers. Grace gets distracted easily and abandons her work, symptoms of her ADHD and a mood disorder, records show. Her Individualized Education Plan, which spelled out the school supports she should receive, required teachers to periodically check in to make sure she was on task and clarify the material, and it allowed her extra time to complete assignments and tests. When remote learning began, she did not get those supports, her mother said.

Days after the court hearing, on April 24, Grace’s new caseworker, Rachel Giroux, made notes in her file that she was doing well: Grace had called to check in at 8:57 a.m.; she reported no issues at home and was getting ready to log in to do her schoolwork.

But by the start of the following week, Grace told Giroux she felt overwhelmed. She had forgotten to plug in her computer and her alarm didn’t go off, so she overslept. She felt anxious about the probation requirements. Charisse, feeling overwhelmed as well, confided in the caseworker that Grace had been staying up late to make food and going on the internet, then sleeping in. She said she was setting up a schedule for Grace and putting a desk in the living room where she could watch her work.

“Worker told mother that child is not going to be perfect and that teenagers aren’t always easy to work with but you have to give them the opportunity to change,” according to the case progress notes. “Child needs time to adjust to this new normal of being on probation and doing work from home.”

Five days later, after calling Charisse and learning that Grace had fallen back to sleep after her morning caseworker check-in, Giroux filed a violation of probation against her for not doing her schoolwork.

Giroux told the prosecutor she planned to ask the judge to detain Grace because she “clearly doesn’t want to abide by the rules in the community,” according to the case notes.

Grace has said in court and in answers to questions from ProPublica that she was trying to do what was asked of her. She had checked in with her caseworker every day and complied with the other requirements of intensive probation, including staying at home and obeying all laws. She had told her special education teacher that she needed one-on-one help and began receiving daily tutoring the day after the probation violation was filed.

Giroux filed the violation of probation before confirming whether Grace was meeting her academic requirements. She emailed Grace’s teacher three days later, asking, “Is there a certain percentage of a class she is supposed to be completing a day/week?”

Grace’s teacher, Katherine Tarpeh, responded in an email to Giroux that the teenager was “not out of alignment with most of my other students.”

“Let me be clear that this is no one’s fault because we did not see this unprecedented global pandemic coming,” she wrote. Grace, she wrote, “has a strong desire to do well.” She “is trying to get to the other side of a steep learning curve mountain and we have a plan for her to get there.”

Giroux declined to comment. Tarpeh told a reporter she was not allowed to discuss Grace’s case.

The May 14 hearing to decide whether Grace had violated her probation, and what would happen if she had, took place at the Oakland County courthouse when the Family Division was hearing only “essential emergency matters.”

Grace’s case was the only one heard in person in the courthouse that day.

Grace’s attorney, concerned about his health, participated by Zoom, though he told the judge it was difficult to represent her without being there. He told the judge he decided not to request a postponement because the family was worried she would detain Grace if they waited for a later court date.

The prosecution called Giroux, the caseworker, as its only witness. In response to questions from Grace’s attorney, she acknowledged she did not know what type of educational disabilities Grace had and did not answer a question about what accommodations those disabilities might require. Her assessment that Grace hadn’t done her schoolwork was based on a comment her mother made to her teacher, which Charisse testified she said in a moment of frustration and was untrue.

Grace’s special education teacher, Tarpeh, could have provided more information and planned to testify but had to leave the hearing to teach a class, according to the prosecutor.

Grace and her mother testified that she was handling her schoolwork more responsibly — and that she had permission to turn in her assignments at her own pace, as long as she finished by the end of the semester. And, Charisse said, Grace was behaving and not causing her any physical harm.

The transition to virtual school had been difficult, Grace testified, but she said she was making progress. “I just needed time to adjust to the schedule that my mom had prepared for me,” she said.

Brennan was unconvinced. Grace’s probation, she told her, was “zero tolerance, for lack of a better term.”

She sent her to detention. Grace was taken out of the courtroom in handcuffs.

From March 16, when Michigan courts began limiting operations to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, to June 29, at least 24 delinquency cases involving youth in Oakland County court resulted in placements to juvenile facilities. Of those, more than half involved young people who are Black, like Grace.

Those numbers, obtained by ProPublica from the Oakland County Circuit Court, reflect long-standing racial disparities in the state and county’s juvenile justice system. From January 2016 through June 2020, about 4,800 juvenile cases were referred to the Oakland court. Of those, 42% involved Black youth even though only about 15% of the county’s youth are Black.

A report released last month, which found inadequate legal representation for juveniles in Michigan, noted that research has shown a disproportionate number of youth of color are incarcerated in Michigan overall. Black youth in the state are incarcerated more than four times as often as their white peers, according to an analysis of federal government data by The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit that addresses racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

“It is clear that kids of color are disproportionately involved and impacted by the system across the board,” said Jason Smith of the nonprofit Michigan Center for Youth Justice, which works to reduce the confinement of youth. “They are more likely to be arrested, less likely to be offered any kind of diversion, more likely to be removed out of the home and placed in some sort of confinement situation.”

In Grace’s case, too, she was sent to a facility at a time when the governor had encouraged courts to send children home.

At the county-run Children’s Village, which has space for 216 youth in secure and residential settings, the population was down to 80 last week, according to the facility manager. There have been no COVID-19 cases in the youth population and four workers have tested positive from contacts outside Children’s Village, she said.

During March and April, 97 juveniles were released from Children’s Village by court order, said Pamela Monville, the Oakland County deputy court administrator. “We understood the orders and the concerns to stop the spread,” she said. Judges, caseworkers and attorneys worked together to determine “who could go back to the community,” she added.

Juvenile justice experts and disability advocates decried the decision to remove Grace from her home, particularly when “the state gave clear directives that children, and all people, unless it was a dire emergency, were to be kept out of detention,” said Kristen Staley, co-director of the Midwest Juvenile Defender Center, which works to improve juvenile defense across eight states.

Terri Gilbert, a former supervisor for juvenile justice programming in Michigan and a high-profile advocate, said the system suffers from inconsistencies in treatment and sentencing, aggravated by a lack of public information.

“This is too harsh of a sentence for a kid who didn’t do their homework. … There is so much research that points to the fact that this is not the right response for this crime,” said Gilbert, a member of a governor-appointed committee that focuses on juvenile justice. “Teenage girls act out. They get mouthy. They get into fights with her mothers. They don’t want to get up until noon. This is normal stuff.”

Monville said Brennan, a judge since 2008, “made the decision she made based on what she heard and her experience on the bench.”

But officials at the Michigan Protection & Advocacy Service, the state disabilities watchdog organization, said they were especially troubled that a student with special needs — one of the most vulnerable populations — was punished when students and teachers everywhere couldn’t adjust to online learning.

“It is inconceivable that, given the utterly unprecedented situation, a court would enforce expectations about what student participation in school means that was not tied to the reality of education during a pandemic,” said Kris Keranen, who oversees education for the group.

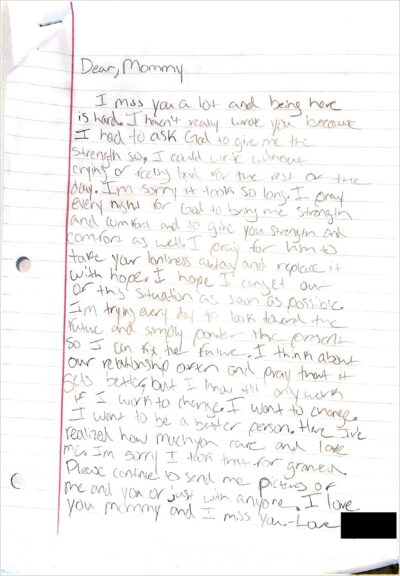

Charisse says the “greatest pain and devastation” of her life was watching Grace handcuffed in the courtroom. She got a letter in the mail a few days later:

“I want to change. I want to be a better person. Here I’ve realized how much you care and love me. I’m sorry I took that for granted. Please continue to send me pictures of me and you or just with anyone. I love you mommy and I miss you.”

On Juneteenth, the day that commemorates the end of slavery, Charisse sat alone at her kitchen table, the wall behind her covered with Grace’s childhood artwork. As the country faced a reckoning over systemic racism, the day had taken on increased recognition and Charisse lamented she and Grace couldn’t mark it together as they usually did, attending programs at church or at the Museum of African American History in Detroit.

Charisse made strawberry lemonade with fresh watermelon, a variation on the traditional red Juneteenth drink, and talked to Grace the only way she could, through a video call monitored by a Children’s Village case coordinator. The longest they had ever been separated before was when Grace attended a leadership sleepaway camp for six weeks over the summer.

“Juneteenth is all about freedom and you can’t even celebrate. What do you have? It has been taken away,” she said to her daughter.

Other than three recent visits, they have seen each other only on screen, including during a court status hearing in early June. On that day, Charisse watched as Grace walked into a room at Children’s Village handcuffed and with her ankles shackled, her mother said.

“For us and our culture, that for me was the knife stuck in my stomach and turning,” Charisse said. “That is our history, being shackled. And she didn’t deserve that.”

At the hearing, both Grace and her mother pleaded with the judge to return her home. “I will be respectful and obedient to my mom and all other people with authority,” Grace said. “I beg for your mercy to return me home to my mom and my responsibilities.”

The judge, however, sided with the caseworker and prosecutor. They agreed that Grace should stay at the Children’s Village not as punishment, but to get treatment and services. She ordered her to remain there and set a hearing to review the case for Sept. 8. By then, it will be a week into the new school year.

On Juneteenth, Charisse and Grace spoke for their full allotted 45 minutes. Grace wore a light blue polo shirt her mother had dropped off a few days earlier. Her hair was pushed back with a Lululemon headband.

Their conversation began with the mundane: Charisse reminded Grace to use her deodorant, and Grace said she needed to get her glasses fixed. But it landed, inevitably, at the frustration they both feel.

“I want you to write in your journal,” Charisse told Grace. She urged her “not to get too comfortable” in detention. “I want you to do what you are supposed to do, but I don’t want you to feel like this is your new norm.”

Grace’s initial weeks in detention were “repetitive and depressing,” she recently told ProPublica in response to written questions.

Grace was required to stay in her locked room from 8:30 p.m. to 8:30 a.m. She couldn’t turn the lights on and off herself and she slept on a mattress on a concrete slab, she said. She passed the time by reading, drawing and watching some TV.

The local school district provided packets of material but no classes. She said that she has not yet worked with a teacher in person or online, and that she meets less regularly with a therapist at Children’s Village than she did at home.

She has since been transferred to a long-term treatment program at Children’s Village, where she has a bit more freedom. Still, she tells her mother, it’s difficult to think about what she’s missing. “Everyone is moving past me now and I’m just here,” she said during the Zoom call.

A Children’s Village case coordinator, listening, tried to be encouraging. “You are doing very well right now,” she said. “Whatever happens, it looks good. You are respectful, you are following the rules.”

Then she told them their time was up.

“Stay strong,” Grace told her mom.

“You stay strong, too,” her mother replied. “I love you.”

“I love you, too.”

ProPublica is using middle names for the teenager and her mother to protect their identities.

Get the latest news from ProPublica every afternoon.

[ad_2]

Source link