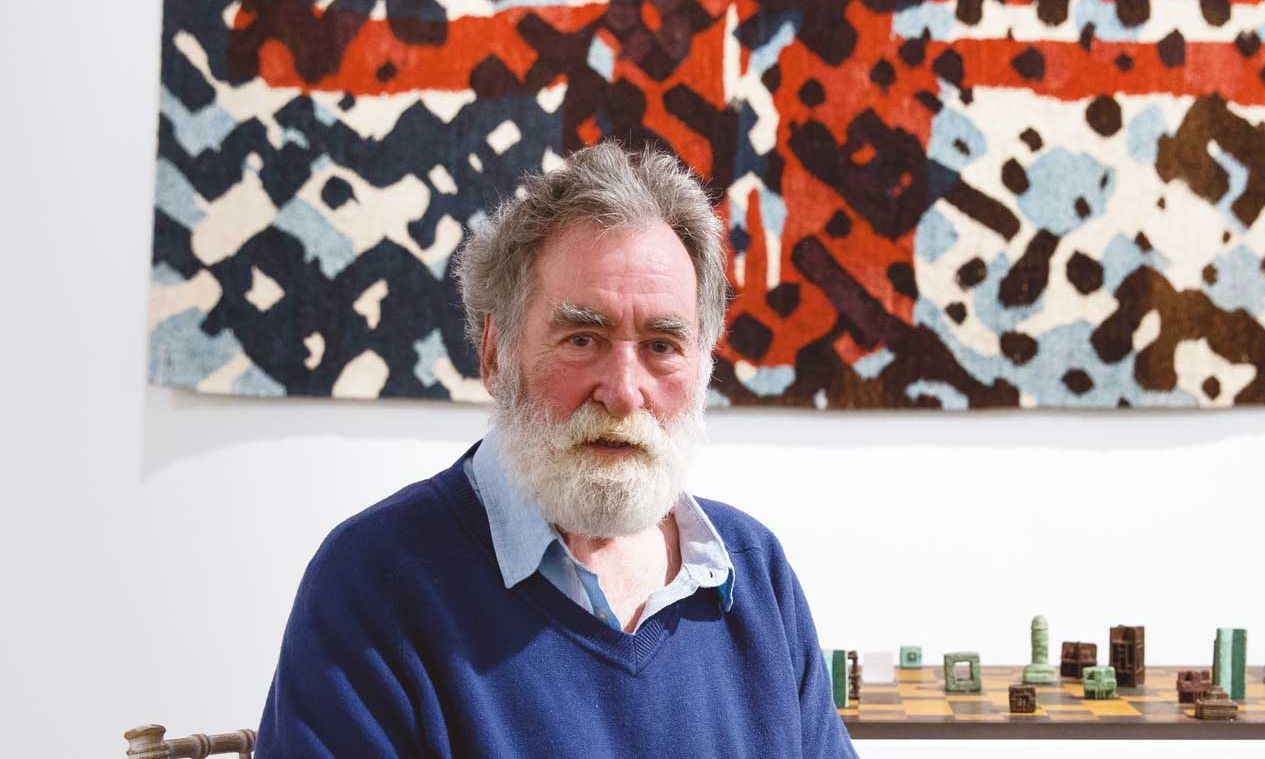

An artist whose drawings and paintings require careful reading and explanation: Tom Phillips, in 2017 Photo: Antonio Parente; courtesy of Flowers Gallery

Back in 1966 I was asked for help by Diane Uhlman, the left-wing yet high-born, English-as-they-come wife of the faux-naive refugee artist Fred Uhlman. She wanted me to clear up the remnants of the Artists International Association (AIA) gallery, in Lisle Street, central London, and to return works I found to artists as far as I could. There I found a small green-bordered, collaged, lithograph print, For Morton Feldman—the New York avant-garde composer contemporary of John Cage—by an artist then unknown to me, Tom Phillips.

Phillips’s print has on it a baby’s face, lots of music staves criss-crossing, an image of a piano keyboard and a strange word in the middle: “cacoethes”—of Greek origin and meaning “compulsion” or “mania”, a quality that Phillips would have acknowledged he had in spades. As an avant-garde music lover myself, I have got great pleasure over the years from the print, which evokes in an English way what Kandinsky called his “little joys”. Music had clearly influenced the then young Phillips, and, judging by this early work, he seems to have sprung up fully formed as an artist—even if a seemingly endless stream of images and ideas in many media lay ahead.

Tom Phillips was born in 1937 in Clapham, south London, and spent much of his life in a house in Peckham that had been bought by his mother. I got to know Phillips after I joined the Royal Academy (RA) in 1977 where he was later to become the most wonderful chairman of exhibitions, whose aesthetic and political judgement—yes, exhibitions have their political dimensions—was in tune with mine, and a source of huge wisdom and valued advice. For Phillips was nothing if not learned—he seemed like the south London version of the fabled homunculus; he knew about everything and was able to extract knowledge of universal significance from the most banal of daily sources: a park bench, the prostitute cards in phone boxes, and a copy of a seemingly trite novel picked up for three old pence, A Human Document by W.H. Mallock, who had been a noted right-wing Victorian novelist.

Mallock’s title was compressed, in the treatment Phillips made of the book, into A Humument—arguably his most important work—the subject of many iterations over 50 years (1966-2016), via collage and overpainting; what I would prefer to call illumination-overlay. Because, thinking of Phillips, it is difficult not to think of the monk in his (Peckham) cell, with pen and coloured inks spontaneously elaborating inside and outside the borders of the printed margins, deciding what original words, or part words, of his unlikely hero author Mallock should be preserved. The word “opera” might appear, previously part of, say, “operation”; and a squiggle above the phrase “the shortest” might be a reference to Phillips’s 15-or-so-minute opera Irma—a title which arose in turn from another masked-out word.

A fully formed artist: Tom Phillips, For Morton Feldman, silkscreen, 1965, 26.6 x 20.8cm

Phillips played the piano and he was a founding member of the Philharmonia Chorus under the direction of its legendary master, Wilhelm Pitz. I must have unknowingly heard him singing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony under Otto Klemperer or the Verdi Requiem under Carlo Maria Giulini at the Festival Hall, but Phillips equally participated in the London avant-garde music world of John Tilbury, Mary Wiegold, Cornelius Cardew and his Scratch Orchestra, Terry Riley, Brian Eno, and Gavin Bryars.

In spite of recordings, music is in its essence an ephemeral art. Less so perhaps the literary and visual worlds which combined in the heyday of concrete poetry—a form to which Phillips was inevitably drawn. His oeuvre has connections to the works of contemporaries such as Ian Hamilton Finlay and Dom Sylvester Houédard, as he plays with letters, words on bronze cast skulls, within wired crosses, large panels, tapestries, quilts, private meanings and messages. The words are sometimes in complex acrostics and yet the object in front of the viewer has its own particular and recognisable Phillips aesthetic and beauty. And let us not forget his many portraits: Salman Rushdie, with whom he played table tennis, Iris Murdoch, and Harrison Birtwistle. When he painted me, he included a French tricolour because it was 14 July 1989, the 200th Anniversary of the French Revolution.

Phillips was passionate about cricket. He hired the Oval for a match with friends for his 50th. He was also a collector of postcards, interested not only in the image on the front but the nuance of the written message on the back. His amazing book The Postcard Century, published for the millennium—which for him, being something of a pedant, began in 1901—contains 100 chapters to the year 2000, and is a souvenir of a now lost world.

Though Phillips was closely married to his south London, he nonetheless had wide horizons in Europe, the US and most particularly in Africa. He was especially drawn to Ghana, which he visited often, and to Kente textiles, and their yellow and red regal striped patterns that had evolved over centuries, yet seemed to him like modernism avant-la-lettre, though not in the sculptural way that Picasso and his like had previously valued the art of “Africa”.

In Ghana he discovered the world of Ashanti gold weights, a source of bottomless architectural and sculptural invention in miniature. He made a collection of thousands of these beautiful little objects that is a study in culture in itself and gave rise to a small book. But inevitably he was drawn—like his great and all-knowledgeable friend David Attenborough—to collect examples of the arts of Africa more generally, building up an encyclopaedic knowledge of the subject, that led to one of the great shows at the RA, Africa: The Art of a Continent (1996). The exhibition bore witness to the earliest origins of human tool-making, more than one and a half million years ago in the Olduvai Gorge in what is now Tanzania. There are many wondrous, even crazy, stories around this exhibition. But most important was the revelation of the amazing creativity in so many parts of Africa south of the Sahara—at the time of Christ, or for that matter during the period of the European Renaissance, long before colonialism was underway with all its complex and devastating effects.

Phillips’s paintings and prints require careful reading and explanation. His house/studio was overflowing with books on every subject. He embarked on complex, never to be completed encounters with Dante and his worlds, together with the film-maker Peter Greenaway. He never got on a bus without a copy of the Times Literary Supplement, because of the random information it surely contained. He was a devotee of Scientific American for the same reason. He absorbed it all with love and pleasure and yet always with a strong sense of irony that hailed from a self-conscious melancholy. Food, wine, cigarettes were further pleasures, though lunch at home was usually little more than a tin of sardines. But he lived his life, with his own sense of the significance of art, to the full. The things, the art, he left behind for us—much of which will find itself in collections at Palazzo Butera, Palermo, and in the Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry, Iowa City—will surely find a place in the collective memory of things.

I just rediscovered on my shelves his book Merry Meetings (2005). For Phillips these were evidenced by typed agendas for gatherings at the RA, the National Portrait Gallery and the British Museum, on whose committees he was “a natural”, but where he used the papers to doodle extravagantly, generating ornamental fantasies that became a unique form. And, just a month or two before his death, he published a “new Humument”: Humbert (2022), a “reworking” of Humbert Wolfe’s Cursory Rhymes (1927).

Some words from Brahms’s German Requiem, a piece that Phillips surely sang at the Festival Hall, found their way into a 1971 collage painting of his (in English: “For all flesh is as grass and all the glory of man as the flower of the grass”). Yet his works of more than 60 years are, in all their multifarious forms, endlessly fascinating and, in their self- and cross-referencing ways, as though one.

• Trevor Thomas Phillips; born London 25 May 1937; RA 1989; chair, Exhibition Committee, Royal Academy, London 1995-2007; CBE 2002; Slade professor of fine art, Oxford University 2005-06; married 1961 Jill Purdy (one daughter, one son; marriage dissolved 1988), 1995 Fiona Maddocks; died London 28 November 2022.