[ad_1]

Bruce Nauman, Wax Impressions of the Knees of Five Famous Artists, 1966, fiberglass and polyester resin, 15⅝ x 85¼ x 2¾ inches.

BEN BLACKWELL/©2018 BRUCE NAUMAN AND PROLITTERIS, ZURICH/SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

In a recent tirade about “fake news,” Donald Trump told an audience of military veterans in Missouri, “What you’re seeing and what you’re reading is not what’s happening.” With that, the world caught up to Bruce Nauman.

From his early studio experiments in Berkeley, California, in the 1960s to his recent revisits to his contrapposto-walk videos, Nauman has always played with stylization and the truth. In one of the first galleries in “Disappearing Acts,” a retrospective at the Schaulager in Münchenstein, Switzerland, was the wryly titled Wax Impressions of the Knees of Five Famous Artists (1966). It was made with fiberglass and polyester resin, not wax, and features knee prints that are Nauman’s own—what you’re reading is not what’s happening. A little farther on is Corridor Installation (Nick Wilder Installation), 1970, a set of narrow corridors down which the viewer is invited to walk. Strategically placed cameras feed confusing images to TV monitors at the end of each corridor. One shows you walking away from the monitor, even as you approach it—what you’re seeing is not what’s happening.

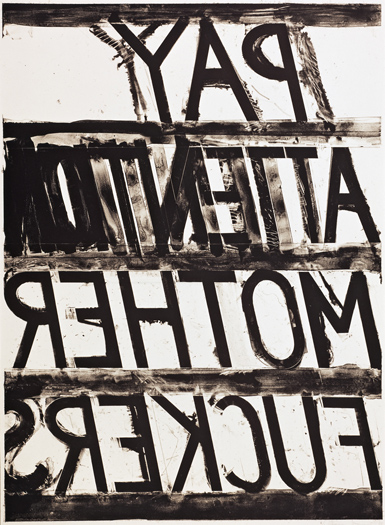

Bruce Nauman, Pay Attention, 1973, lithograph, 38¼ x 28¼ inches.

PHOTO: ©1973 BRUCE NAUMAN AND GEMINI G.E.L.; ART: ©2018 BRUCE NAUMAN/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COLLECTION ROBIN WRIGHT AND IAN REEVES

Even farther along is what appears to be merely a large, white, spiral-shaped sculpture suspended from the ceiling whose title—Model for Trench and Four Buried Passages (1977)—reveals it to be a template for a set of tunnels to be placed underground. Nauman is asking the viewer to “Pay Attention Motherfuckers”—as per the title for a 1973 lithograph placed next to Model for Trench.

Pointing to works like Corridor Installation, critics have written of Nauman’s work as trafficking in paranoia. I prefer to think of it as being engaged in a form of radical skepticism. His art is telling you to be leery, to assume you’ve never been fully informed, to take nothing for granted. Under the expert curation of Kathy Halbreich—a master at shepherding challenging artists into the museological pen—and a Schaulager team headed by Heidi Naef and Isabel Friedli, the retrospective (which will open on October 21 at the Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1 in New York) has done Nauman justice. At this moment, his art is precisely what we need.

Halbreich curated an earlier Nauman retrospective at MoMA, in 1995. Numerous critics then felt compelled to warn visitors of an experience that was loud, abrasive, and chaotic. Looking back now, it is easy to see a certain prescience and foreshadowing in that no-funhouse, not only of museums turning into sites of spectacle and entertainment (Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirror Rooms,” Newfields’ “Winterlights”), but also the myriad ways in which our lives were soon to become noisier, with social media grinding out messages, posts, and tweets, and cell phones bleating and vibrating. Despite including some of the same pieces—a video of a tormented clown screaming “no no no no no” (Clown Torture, 1987) and a couple of TV monitors showing two actors reading the same lines using different intonations (Good Boy Bad Boy, 1985)—the newer Nauman show is notably quieter.

Bruce Nauman, One Hundred Live and Die, 1984, neon tubing with clear glass tubing on metal, 118 x 132¼ x 21 inches.

DOROTHY ZEIDMAN/©2018 BRUCE NAUMAN AND PROLITTERIS, ZURICH/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND SPERONE WESTWATER, NEW YORK/COLLECTION BENESSE HOLDINGS, INC.

Or maybe, as signaled by Trump, the world has just caught up. Take Get Out of My Mind, Get Out of This Room (1968), set in a small room in the museum with a single light bulb glowing weakly and a whispery voice repeating the words of the title over and over. In the echo chamber of Twitter, say, no one can ever get anyone else out of her or his mind. In Nauman’s 1984 neon text masterpiece 100 Live and Die, phrases like “Know and Die” and “Cry and Live” blink on and off. Back when he made that piece, you had to go to Las Vegas for a comparable barrage—nowadays, staccato signs flash at us relentlessly all day every day, online and off.

Another exhibition in Basel, “Bacon Giacometti” at the Fondation Beyeler, offered a different yet related take on the human condition. Catherine Grenier, who curated the show, fixed on common ground between Bacon’s trademark distorted perspective and meat-slab figurative ambiguities, and Giacometti’s sculptural surrealism and skinny striding figures. (The image of the cage shows up in both artists’ work.) In her catalogue essay, Grenier identified “crucial themes” for both artists as “[t]he modern individual and his or her complex relationships with other individuals and groups, the manifold forms of existential distress and suffering, loneliness and pain, sexuality and violence, life and death.” Replace “modern” with “postmodern” and these are the same driving forces behind Nauman.

Bruce Nauman, Corridor Installation (Nicholas Wilder), 1970, wooden wallboards, water-based paint, three video cameras, scanner, frame, five monitors, video recorder, video player, and videotape, dimensions variable, installation view, at Nicholas Wilder Gallery, Los Angeles, 1970.

©2018 BRUCE NAUMAN AND ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/FRIEDRICH CHRISTIAN FLICK COLLECTION IM HAMBURGER BAHNHOF, BERLIN

Bacon’s famous screaming pope can be seen as a spiritual father to the figure in Nauman’s 1988 video Clown Taking a Shit, who is just trying to crap in peace. Giacometti’s distended sculptures seemed to anticipate the lean young Nauman in the midst of one of his “Beckett Walk” videos, lumbering in a limb-locked manner inspired by Samuel Beckett. The plinths beneath some of Giacometti’s figures were slanted, calling to mind the so-called “slant step”—an ambiguous, seemingly useless object (who could stand on a slanted step?) that the budding conceptualist/post-minimalist Nauman and his cohort of “funk” artists found discarded in San Francisco in the 1960s and reused in multiple works. (The Schaulager had one of Nauman’s drawings of the slant step.) Human-condition-wise, it turns out, existentialists, conceptualists, and funksters agree: We’re all on a slippery slope.

The most Naumanesque moment in “Bacon Giacometti” was in the final gallery, where, using lines projected on the floor to delineate the layout and photographs projected on the walls, the museum attempted to re-create the artists’ prodigiously cluttered studios. Here, in full force, was the myth of the studio as the site of creative genius. It’s a myth that has fascinated Nauman throughout his career, from early videos of him bouncing a ball or doing that “Beckett walk” in the studio to a photograph of him “failing to levitate” in the same space, propped up on two chairs like a human sawhorse. Then there is his 2001 work Mapping the Studio I (Fat Chance John Cage), a video recording of what goes on in his studio at night when he is not there (see: the adventures of a cat seeking mice).

Another work of the kind, which Nauman made in 1967 and hung in the window of his studio, is one of his best-known neons, with a message reading: “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths.” With those words, he is daring you to believe (or disbelieve) him. For Nauman, questions about who has made the art you are looking at—and what art, and even an artist, is—have always been paramount. One mustn’t simply read or listen to the words but, as important, consider the speaker. It makes less sense to regard Nauman’s oeuvre as a body of work than as the work of a body.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 132 under the title “ ‘Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts.’ ”

[ad_2]

Source link