[ad_1]

But don’t panic yet.

One critic of the research says it “doesn’t hold water,” while another says that the paper’s hypothesis is only speculative.

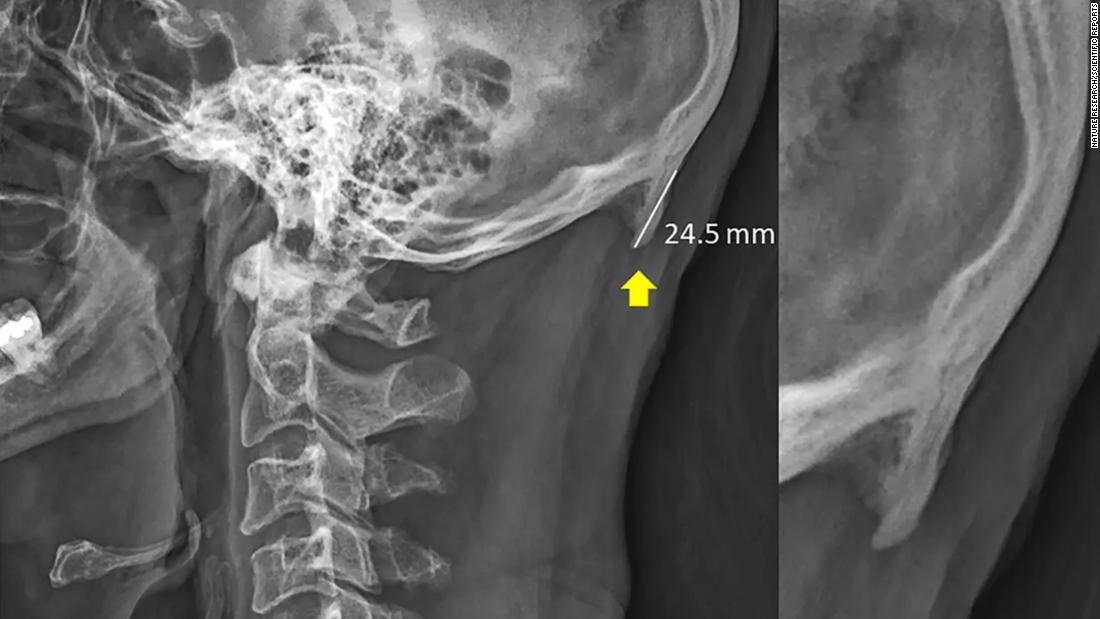

In their research, Shahar and Sayers said young people may be developing tiny hornlike spikes at the back of their skulls, possibly caused by the shift in the weight of our heads from the spine to the muscles at the back of our head and neck. This anatomical feature is called an external occipital protuberance, or EOP.

The possible cause of this shift in weight? You probably guessed it. The researchers hypothesize that it is due to poor posture from people craning their heads forward more because of phone and mobile device usage.

However, just don’t call it a horn.

“We have not called the enthesophytes growing out of the occipital bone horns,” Sayers said in an email. “They are not horns — this is a term used by the media.”

For their first study, the two researchers set a threshold of 5 millimeters to record an EOP, and considered it an enlarged EOP if it exceeded 10 millimeters in length. They discovered that 41% of the participants, ages 18 to 30 years old, had an enlarged EOP in their skulls.

These types of bone spurs are more commonly found in the elderly, and are assumed to be a normal part of the aging process. However, Shahar and Sayers believe that the advance of technology has changed the timeline for this type of bone growth.

Their second paper studied a larger sample size of 1,200 X-rays for subjects 18 to 86 years old. Thirty-three percent of the subjects were found to have the bone growth, but oddly enough, the growth was found to have decreased with age.

But not everybody agrees with the researchers’ ideas.

Hawks noted that the study lacked a results table that would have offered more detail about their findings, and there are contradictions between the text and charts in the study.

Hawks believes the data presented is not being consistently measured.

“We have no data linking phone use with EEOP,” Sayers tells CNN. “We have, however, suggested that EEOP is linked with excessive FHP (forward head posture) and sustained cervical flexion. The confusion with our analysis seems to stem from misinterpretation of one of our graphs, which shows the percentage of EEOP within each sex. These are not overall or absolute data.”

That last point by Sayers is important, as a lot of the criticism levied against Shahar and Sayers stems from the lack of data and information presented in the study.

“There is no information about the duration or frequency of hand-held device usage in this study, so it is not possible to draw any correlation between the observations of enlarged EOPs and hand-held device usage,” Dr. Mariana Kersh, an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering at The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Director of the Tissue Biomechanics Laboratory, tells CNN. “There is definitely no cause and effect demonstrated in this study.

“The hypothesis regarding the role of hand-held device usage is only speculative and not based on any data presented in this study.”

The study lacks a control group, and the X-rays are taken of patients that had to visit a chiropractor with severe enough neck issues to have X-rays taken, which may not offer the best picture of the overall population.

Changing posture alone may also not be enough to spur such a significant bone adaptation.

“Bone adaptation usually occurs in response to dynamic repetitive movements that the body is not accustomed to seeing,” Kersh said. “The strain on the bone must also be of sufficient magnitude (higher than usual) to induce adaptation. With what we know about how bone responds to mechanical loading, changing posture alone would likely not result in bone changes, especially within a single lifetime.

“Inducing bone adaptation through musculoskeletal loading is possible, but requires increased, repetitive, atypical loading which are different from the hypothetical loads suggested by Shahar and Sayers.”

While Kersh does not believe that bone adaptation is possible based on the suggested hypothetical loads, Shahar stands by the research.

“The detection of large enthesophytes in the tested young adult population provides evidence that musculoskeletal degenerative processes can start and progress silently from an early age,” Shahar said in an email. “Our hypothesis, linking these degenerative changes with the use of modern technologies, provides a warning to the premature development of preventable musculoskeletal degenerative processes with the sustained inappropriate posture.

“The findings of this project suggest that mechanical load is not to be overlooked in the management of conditions that are associated with structural remodeling of the skeleton.”

Raising awareness around this issue was one of the main goals of Shahar’s and Sayers’ research, and despite some of the negative reactions to their studies, the intense interest surrounding it means they accomplished one of their goals.

“We’re really pleased that our paper has raised so much interest,” says Sayers. “As a result, we encourage researchers to do their own data collection and analysis.”

Update: This story has been updated with comments from researchers David Shahar and Mark Sayers.

[ad_2]

Source link