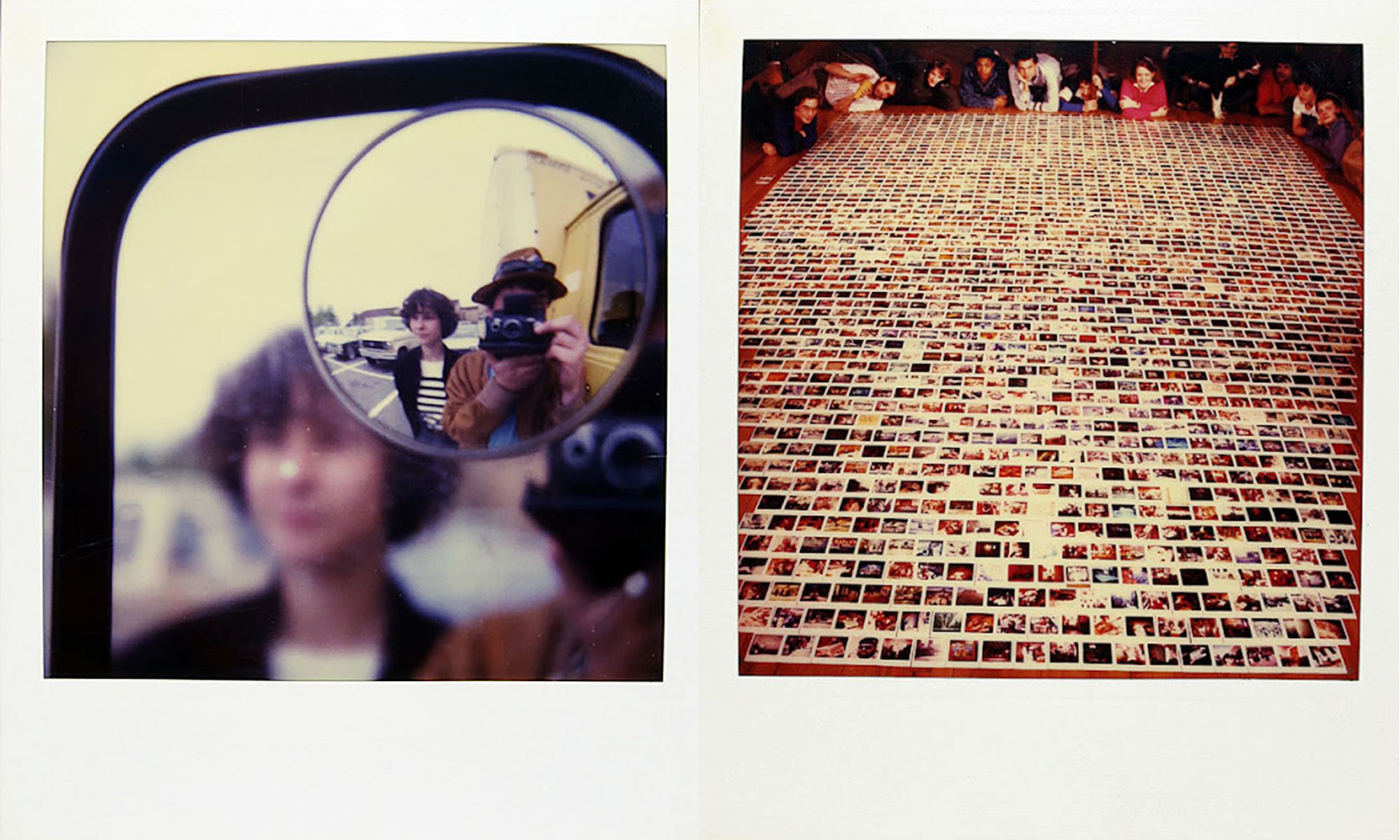

Jamie Livingston, Sunday, April 28, 1985 (left, 1985) and Saturday, March 30, 1985 (right, 1985) Jamie Livingston

In 1997, Jamie Livingston, an artist and film-maker, died on his birthday at the age of 41 in the hospital in New York where he was born. By then, Livingston had taken and saved more than 6,700 Polaroid photos, one every day for 19 years.

His project Photo of the Day (or POD)—self-portraits, candids, landscapes, celebrity snapshots, circus pictures, nudes and even memento mori shots of Livingston’s final hospital days—eventually became a no-budget exhibition in 2007 that snaked through the halls of a building at Bard College, where Livingston began the project.

Surging on the internet after that, POD resurfaced as an overnight sensation in China, recalls Hugh Crawford, a photographer and college mate who mounted the Bard show. “There was this whole thing in China about the auspiciousness of what happened on the day you were born, so everybody in China wanted to see that,” he says.

The enigmatic story of Livingston and his pictures is now the subject of a musical performance for the stage, Number Our Days: A Photographic Oratorio, with orchestra, soloists and choruses, which premieres this week at the Perelman Performing Arts Center in New York (12-14 April). Images from POD, gigantic blow-ups of the Polaroids, will be onstage behind the choruses.

Jamie Livingston, Thursday, June 27, 1985, 1985 Jamie Livingston

The libretto, “elicited and distilled” by David Van Taylor, who is also credited with the oratorio’s concept, is drawn from interviews with people whom Livingston photographed. Its title comes from a passage in Psalm 90 of the Book of Psalms in the Bible, an exhortation to live a good life every day: “Teach us to number our days, so that we may gain a heart of wisdom.”

The oratorio’s composer, Luna Pearl Woolf, says taking the pictures was “something of a spiritual practice, which turned out to be important to people around him, and to people all over the world. We’re not exactly making art about an artist. We’re making art about a phenomenon.”

Livingston’s pictures, like the oratorio’s choruses, can evoke camaraderie and community. They can also feel like ephemera caught in a time capsule. While the pictures capture the spirit and memory of a single second—and no more than one second—the same Polaroids, sometimes frayed and faded, can seem like meditations on our inherent impermanence.

Livingston’s pictures, taken on a Polaroid SX-70 up to the day of his death—ten years before the iPhone launched—mark a moment in image-making somewhere between Andy Warhol’s signature Polaroid snapshot and the near-infinite profusion of photos on Instagram.

Linda Shaffer, Livingstone’s widow, eager to donate the images to an institution, rejects any connection between the POD pictures and Instagram. For one thing, Livingstone had an actual camera. “I’ve read that he was the godfather of Instagram,” she says. “He really was the opposite, because it was so rule-based. It was a ritual.”

Jamie Livingston, Thursday, December 5, 1996, 1996 Jamie Livingston

Why Livingston began the project is unclear, A few years into POD, presenting a short film about the project, Livingston said his expanding Polaroid trove, taken one per day, “continues until my death or the death of the medium, whichever comes first”.

“Jamie was an artist who believed in practice, not in theory,” says Van Taylor. “The meaning of Photo of the Day, even to him, changed over time. Whatever his intention was as he got into it, I don’t think he could have conceived what it would mean if he continued doing it, and I don’t think he did.”

Others can make up their own minds, aided by the self-published volume Some Photos of That Day; 6754 Polaroids Dated in Sequence. The 11-pound POD visual “bible” was planned to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Livingston’s death. With logistical delays, it became available in 2018. It is the closest thing to a POD catalogue raisonné, including annotated reverse sides of many pictures.

“The whole point was its completeness,” says Hugh Crawford, who edited and published the book, and created a website for Livginston's project. “I sold about a quarter of them so far,” adds Crawford, who had 2,000 copies printed in China. “I have 12 tons of books sitting at home.”