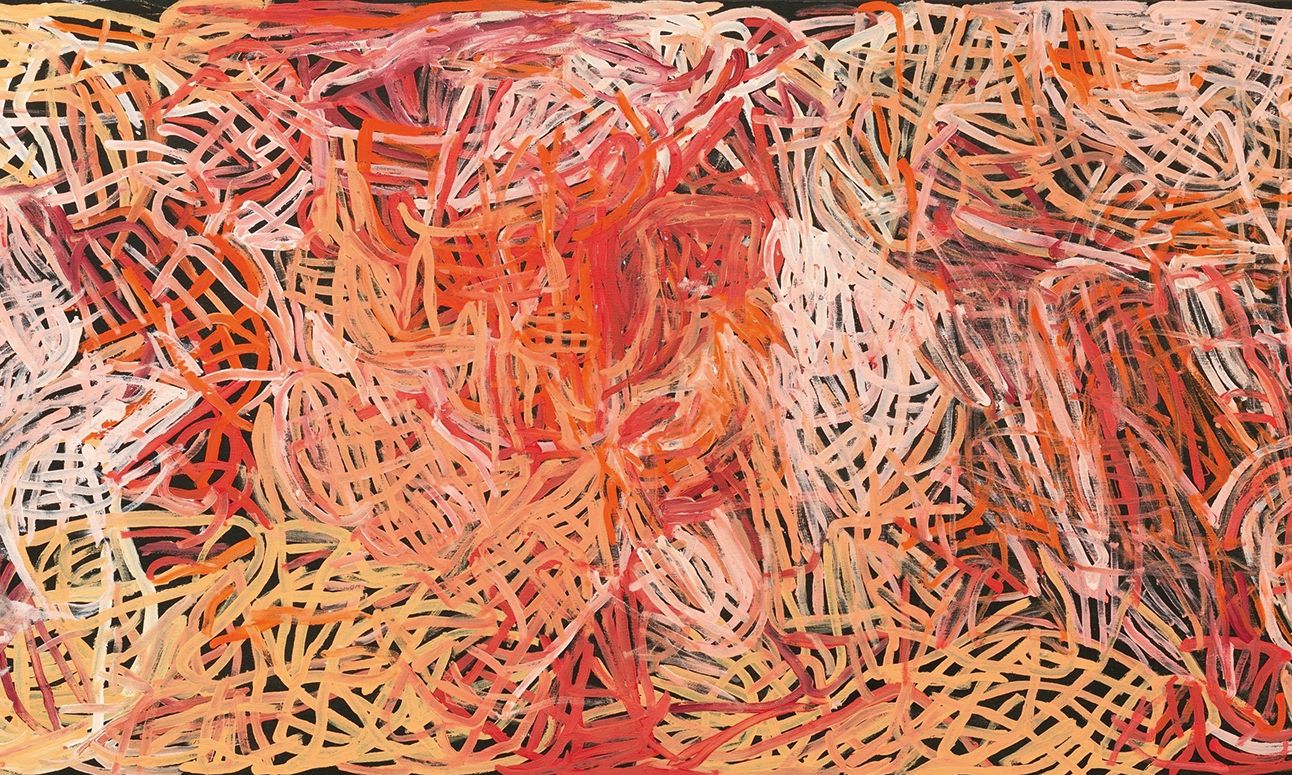

Emily Kam Kngwarray created Yam awely in 1995 during the most prolific period in her life, when she was creating, on average, around one work every day © The artist/Copyright Agency

“She just painted her country, and all things that were significant to her,” says Kelli Cole, the co-curator of a major survey of the late Aboriginal artist Emily Kam Kngwarray at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra. “Kama, which is seed, the pencil yam, emu; awelye, the Anmatyerr word for ceremony; and Alhalker, which is her country—those [themes] are in every one of her works.”

The exhibition, which includes textiles, works on paper and paintings, has been assembled by Cole and fellow Indigenous curator Hetti Perkins, and will chart the career of an artist who, with no knowledge of international visual arts practice, managed to create a vast body of work comparable with the likes of Agnes Martin, Sol Lewitt and Ellsworth Kelly.

Kngwarray (1910-96) was from Utopia, an Aboriginal community 250km north-east of Alice Springs in Australia’s Northern Territory. Although she had produced textile designs on fabric since 1977, it was Kngwarray’s first work on canvas, Emu Woman (1988-89), made for a landmark group exhibition organised by Utopia’s art coordinator Rodney Gooch in 1988, that saw her receive widespread attention. Featuring distinctive gestural brushstrokes used in traditional women’s ceremony, and dots in white, yellow and reddish brown representing the underground seedpods of the pencil yam, Emu Woman demonstrated Kngwarray’s propensity to express her rich culture on canvas.

Kngwarray’s Seeds of Abundance (1990) uses a dot painting technique © The artist/Copyright Agency

From 1988 until her death eight years later, Kngwarray produced around 3,000 paintings—roughly one per day. During this period, demand for her work was so high that the gallerist Christopher Hodges regularly chartered a plane to drop off fresh canvases and whisk away finished paintings. Consequently “there wasn’t much story [about each work] that they could get from her”, Cole says. Kngwarray would simply say “untitled” or “awelye [ceremonial]” to Gooch, and “he thought she didn’t want to give much more information”, Cole explains.

When Kngwarray’s works went on show, alongside those of fellow Australian artists Yvonne Koolmatrie and Judy Watson at the Venice Biennale in 1997, many critics assumed she was an anomaly. But as Perkins, who also curated the Venice show, explained at the time: “The possibilities of Aboriginal art practice are infinite and can have relevance and resonance outside their immediate cultural context while maintaining the integrity of speaking from within that context.”

Kngwarray’s meteoric rise resulted in her being singled out from her community, but this show aims to “reposition Emily back into her community”, Cole says. “It was [her] story that she painted, but [the Anmatyerr] people are still painting that same story,” Cole adds. Now, through extensive consultation, Kngwarray’s descendants are telling her story and revealing new details about the artist’s work. The curator gives as an example a “couple of paintings that have this amazing, lush green that no one’s ever identified before” but when it was shown to the Anmatyerr women, the green was immediately recognised as the distinctive colour of emu eggs from a creation story. “Every single photograph, every painting, every quote, everything has been taken back to the community for her family descendants and the artists that we’ve worked with to approve,” Cole says.

Kngwarray's Untitled (awely) (1994) © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency

Another change, following consultation with the community, has been the NGA’s adoption of the Anmatyerr spelling of Kngwarray’s name, in contrast to the previously widespread use of Emily Kame Kngwarreye.

The exhibition will include several important loans, such as early batiks, two recent NGA acquisitions, and Alhalkere—Old Man Emu with Babies (1989), acquired by the actor Steve Martin at the Sotheby’s New York Aboriginal art auction in May 2022. The show will not only be the most comprehensive survey of one of Australia’s most “significant artists”, Cole says, but it will also position Kngwarray “within her community that she never left—in a sense that was the biggest part of her life.”

• Emily Kam Kngwarray, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2 December-28 April 2024; Tate Modern, London, opening 2025