[ad_1]

Back in 1989, the Big Apple was an open, bubbly pot of hell …

April 19, 1989 was the height of the crack epidemic and the city was a hotbed of violence. In the first half of the year, 837 murders were reported, as were 1,600 rapes, more than 43,000 robberies and 34,000 assaults, according to The New York Times. By today’s comparison so far in 2019, according to NYPD CompStat data, there have been 103 murders, 706 rapes, 4,400 robberies and 7,400 felony assaults.

There was an overarching racial tension in the city with whites and non-whites easily taking jabs at one another, pointedly expressed in Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, which was released that summer.

New Yorkers of all backgrounds were terrified, demanding a remedy to the abject violence in addition to help and understanding of how drug addiction can ravage whole families and neighborhoods, not unlike the opioid crisis today. People put a lot of faith in the city’s first Black mayor, David Dinkins (who won that year by a narrow margin), hoping that he could do with crime what outgoing mayor Ed Koch could not.

READ MORE: Despite large settlement, Central Park Five say the pain of their ordeal still lingers

Then one fateful spring night, prosecutors, police and the political establishment got its chance. Trisha Meili, then a 28-year-old white female investment banker went jogging in Central Park. She couldn’t have known that as many as 35 teenagers were also in the park that night participating in what was labeled as “wilding,” or randomly attacking unsuspecting people.

By the end of the evening, dozens of Black and Latino teens had been stopped and interrogated by police over these random attacks. Meili’s case, however, was much different. She was the victim of a particularly brutal rape, beaten to the point of permanent brain damage, her skull fractured, her eye socket crushed, and left to die by a shallow, muddy ravine in the park.

Of the young men arrested, police linked Meili’s rape and assault to Raymond Santana, 14; Antron McCray, 15; Yusef Salaam, 15; Kevin Richardson, 14; Korey Wise, 16; Clarence Thomas, 14; and Steve Lopez, 15.

Thomas was released later when a grand jury took no action against him. Lopez pleaded guilty to another robbery that took place in the park and was never charged with assaulting Meili. The other five young men’s lives were completely turned upside down as the incident drew local, then national, and finally international attention and became known as “The Central Park Jogger” case, emphasizing Meili’s ordeal.

READ MORE: When They See Us’ sparking calls for Linda Fairstein book boycott

The outrage placed focus on getting convictions for the barbaric crime and the five boys, all Black and Latino, were turned into teenaged pariahs by the media, even moving then-wealthy real estate tycoon Donald Trump to take out a full page ad in the Times calling for the return of the death penalty to New York. He maintains his belief in their guilt to this day.

Several individuals worked feverishly to win convictions placing all five boys behind bars for between six to 13 years on various assault and attempted murder charges. Today, everyone knows that these individuals were responsible for a gross miscarriage of justice, but while the Central Park 5 have lost years behind bars, many of the people responsible for putting them there have gone on to live the good life.

Here are the major players and what became of them in one of the most infamous legal dramas in New York City history.

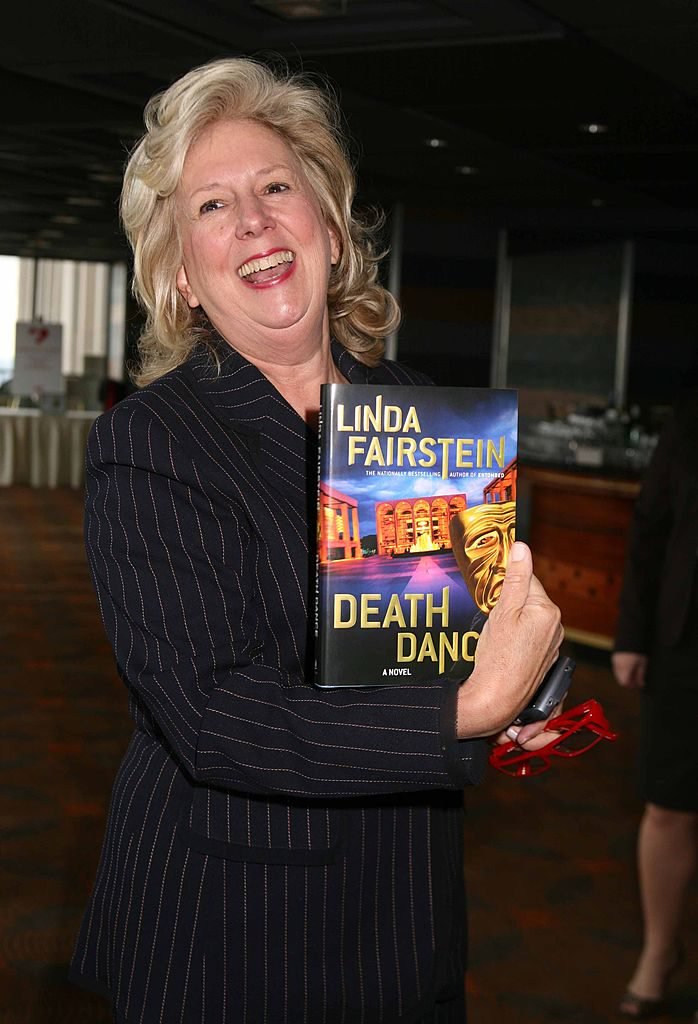

Linda Fairstein, Manhattan D.A. Sex Crimes Unit Head

WHAT SHE DID: In 1989, Linda Fairstein was the head of the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office Sex Crimes Unit, charged with convicting rapes and sexual assaults. She assigned Elizabeth Lederer to the Central Park Jogger case almost immediately (replacing assistant district attorney Nancy Ryan) and assembled a team determined to respond to a fear-based citywide demand to get a handle on youth crime.

Fairstein was said to be so zealous, according to a 2002 Village Voice article, that she even became verbally abusive to Sharonne Salaam, Yusuf Salaam‘s mother. “She came bounding at me in the police station like some Joan of Arc crusader type,” said Salaam. “I had never seen anything like it.

“At one point,” she continued, “I was hyperventilating and I asked for water and Fairstein said there was just no water in the building. It was very strange.”

Once evidence surfaced exonerating the Central Park Five, Fairstein railed against the development. She maintained that although the DNA may have made Reyes the main culprit, the teens were participants and their confessions (which they maintained were coerced) proved it.

“[Reyes] completed the assault,” she told The New Yorker in 2002. I don’t think there is a question in the minds of anyone present during the interrogation process that these five men were participants, not only in the other attacks that night but in the attack on the jogger.”

WHERE IS SHE NOW?: Since the time of the case, Fairstein has been known not only as a determined prosecutor but also as a New York socialite and a best-selling author, having written two dozen titles, most of them legal thrillers. Last year, she wrote in a letter to the editor of The New York Law Journal that the confessions of the boys “were not coerced” and that the environment in which the questioning was done was respectful and calm.

Not of all her accolades have come without scrutiny. Her book “Blood Oath” was honored by the Mystery Writers of America with a Grand Masters Award, but it was rescinded in November 2018 due to the objections of many of the group’s members. She fired back at the group, defending her stance.

The book, however, remained a best seller and she has been on a book tour through much of this year.

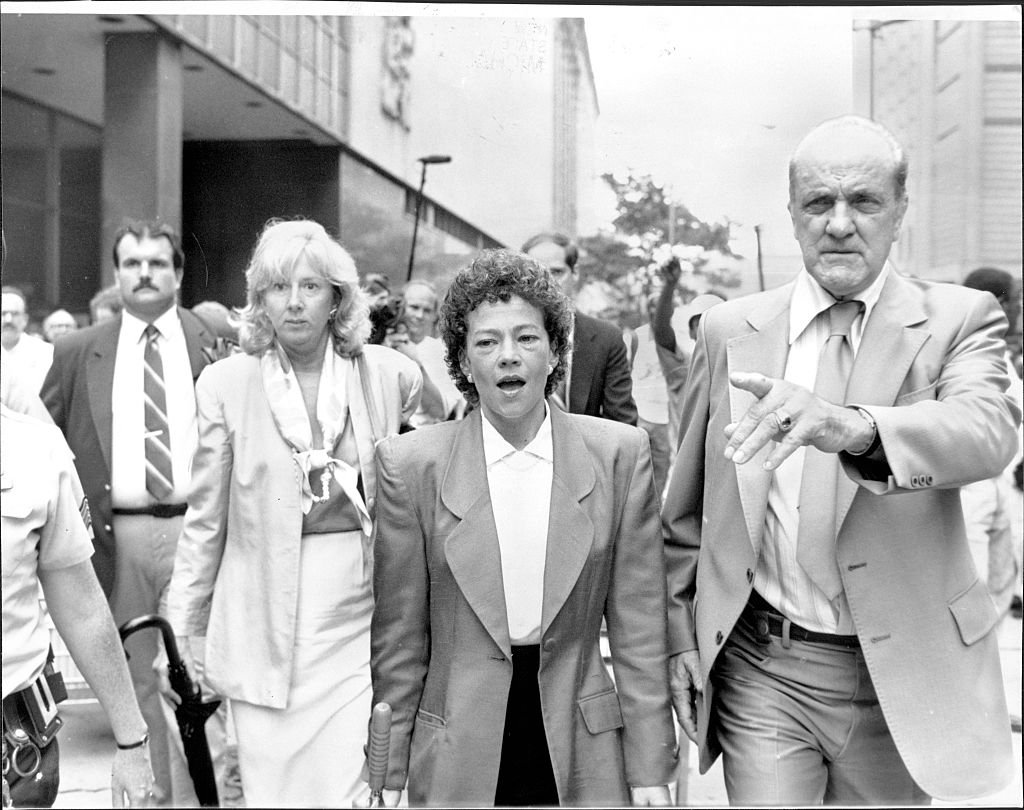

Elizabeth Lederer, Lead Prosecutor

WHAT SHE DID: It fell to the Assistant District Attorney Elizabeth Lederer to present the evidence against the five teens to a jury. She had already visited Meili in a hospital and observed: “Her head was in a bandage turban. Her face was swollen. She had tubes in her mouth and nose,” she told Oprah magazine in 2002. Meili, however, also could not remember the attack. The prosecution used confessions from the five boys that did not prove they assaulted Meili, but placed them as accomplices to the crime, each implicating the other. Ultimately, she won her case, sending the defendants to juvenile facilities for the rest of their teen years and into their adult lives.

Later, mistakes in her prosecution were pointed out. For example, she argued that hair found on one of the defendants matched the victim, which DNA evidence years later proved to be wrong. It also proved that semen in Meili’s rape kit did not match any of the five teens, but matched serial rapist Matias Reyes, who later confessed to raping and beating Meili.

WHERE IS SHE NOW?: Today, Lederer does not speak publicly about the case. She is still an assistant prosecutor with the Manhattan District Attorney’s office with a long record of successful convictions, even in cold cases. She is also an adjunct law professor at Columbia School of Law. After the 2012 Ken Burns documentary, Lederer became the target of a student petition to remove her from the school due to her role in the case.

Tim Clements, Assistant District Attorney

WHAT HE DID: One thing that the co-prosecutor Tim Clements, who was also assigned to the case believed when the Central Park Five were exonerated was that even if Reyes says he acted alone, that his admission is highly questionable.

In an interview with the Daily News last year, he said that the facts point out that the teens were in Central Park that night causing trouble. He also backs Lederer belief that the boys’ parents were there and that no coercion went on.

“My job was to make sure everyone was quiet so the interviews wouldn’t be interrupted,” he told the NY Daily News. “There were parents present. In that situation, you can’t coach them, you can’t tell them what to do.”

He goes on to say that the teens made other confessions about attacking another individual that night, who was later identified as John Loughlin, a schoolteacher who also was jogging in the park. It was his robbery that Steve Lopez ended up doing time for in prison.

“They identified their own victims. In many of the cases, we didn’t know who the victims were, so how do the police coerce statements from people about facts that they weren’t even aware of?” said Clements.

Clements also said prosecutors told jurors that the DNA that was examined matched someone else, but he felt it didn’t clear the defendants and made it likely that they was part of the chaos of that night.

“When Reyes came forward it was a relief…It’s not surprising that he (perhaps) was with this group or joined it later.

“The facts are the facts,” he added. “It’s unconscionable to me that anyone thinks they were not in the park that night and were not causing mayhem.”

WHERE IS HE NOW?: Clements left the Manhattan D.A.’s office in 1991 and hasn’t been able to speak about the Central Park Five because he was advised not to as their civil suit moved forward. The outcome of which was a $41 million settlement with New York City, which he vehemently disagrees with. He is now a partner at a Cleveland law firm where he practices general corporate law and also represents nonprofit organizations among other clients.

Eric Reynolds, NYPD Central Park Precinct

WHAT HE DID: Back in 1989, Officer Eric Reynolds was a 29-year-old cop, raised in the Bronx and was already an eight-year NYPD veteran when the arrests were made in connection with the youths believed to be linked to Meili’s rape.

He told an audience at Suffolk County Community College in Long Island, N.Y., last November that he thought what he’d seen places guilt on the boys he had in custody. When it turned out there was compelling evidence that they were not guilty of the rape he said “I was sick to my stomach. I wracked my brains trying to figure out how did we get this wrong.”

Reynolds and his partner Bobby Powers were assigned to the Central Park precinct that night when, around 8 p.m., they received numerous 911 calls about groups of youths carrying out attacks. Before the evening was over, Reynolds had arrested Santana, Lopez and Richardson and identified McCray. He also says that the teens were not coerced in their confessions.

“If they all said the same exact things, then maybe I would think [they were coerced] But they didn’t,” he told the Daily News a year ago. “Look at the video statements. They stand up and demonstrate (what happened).”

WHERE IS HE NOW?: Reynolds said he watched in disgust 13 years later when the convictions of the Central Park Five were vacated due to Reyes confessions. Like the others involved in the prosecution, he believes Reyes did not act alone. He was also angered when the city settled with the men because a trial would have brought out more evidence and he believes proof would have placed them with Reyes.

“If we had gone to trial in their lawsuit, we wouldn’t be having this conversation because all the facts would have come out,” he said, noting he was never named as a defendant. “It would have been clear they participated and Reyes didn’t act alone. The evidence supported it. They did not want to go to trial. They just wanted to get paid.”

But unlike the others, Reynolds believes that the settlement had political motivations. He contends that political hand-washing from New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio‘s administration for the support of Rev. Al Sharpton during his 2013 campaign was one particular occurrence that led to the $42 million pay day for the five men.

“Once he has Al Sharpton’s endorsement and once he’s saying he’s going to give money to these poor kids who were railroaded and this extreme injustice has taken place and white cops have railroaded them and all this bullsh*t, he’s going to get their votes,” he said.

Reynolds is now retired from the NYPD not long before the case was vacated. The Daily News reports he started working on a book about the case after the 2012 Ken Burns documentary was made.

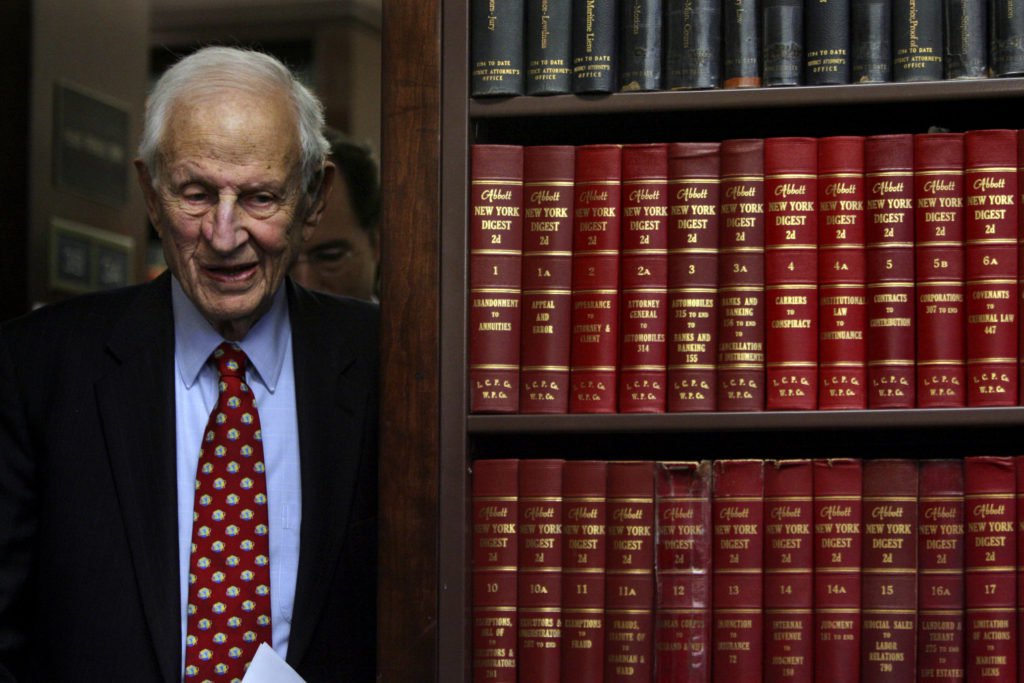

Robert Morgenthau, N.Y. District Attorney

WHAT HE DID: In his tenure as Manhattan D.A., from 1975 to 2009, Robert Morgenthau had seen some of the nation’s most high-profile cases ranging from the murder of John Lennon to “subway vigilante” Bernard Goetz to the Tupac Shakur sexual abuse case. His office was known for their successfully wins, but the Central Park Five case is one his team got very wrong and he knew it.

“I had complete confidence in Linda Fairstein,” he told the New York Times in 2016. “Turned out to be misplaced. But we rectified it.” He acknowledges the mistakes, but like the others says that the confessions of the teens were what drove the prosecutions. “Did I feel badly?” he said. “Yeah, I felt badly. We had screwed up. But there were confessions.”

“This court was handpicked by Dist. Atty. Robert M. Morgenthau. They (the teens) were tried by a lynch mob in a lynch court by a specially selected judge.” —C. Vernon Mason, attorney for Antron McCray

That wasn’t good enough for others who felt the case was a miscarriage of justice. Ron Kuby, who served as Yusuf Salaam’s attorney during his initial appeal, was critical of Morganthau and says he could have done more to foster fairness rather than seeking to fill up prisons.

“Robert Morgenthau’s tenure almost precisely tracked the era of mass incarceration,” Kuby told the Times. “He was the dean and he could have used his moral authority to change that trajectory, and he was silent. He was an active contributor to mass incarceration.”

C. Vernon Mason, Antron McCray’s lawyer agreed after he was convicted. “This court was handpicked by Dist. Atty. Robert M. Morgenthau. They (the teens) were tried by a lynch mob in a lynch court by a specially selected judge.”

WHERE IS HE NOW?: At age 99, in his retirement, Morganthau remains active as a philanthropist and with the Immigrant Justice Corps, in which he advises on immigrant deportation cases, according to The New York Post.

Michael Sheehan, NYPD Detective

WHAT HE DID: No surprise here that former NYPD Det. Michael Sheehan believes the investigation was handled correctly by experienced detectives. However, he also agrees with the others that Reyes’ confession turned the entire case on its head despite the work done by the department to place the five teens at the scene of the crime and that their own words should have prevented their full exoneration.

In court testimony records, available through the New York City Law Department, Sheehan testified that he was in the midst of the interrogations including Lederer and took statements from Raymond Santana, but waited until his father was present. At trial, Santana’s lawyer argued that his father was not initially there. He said he also gave him his Miranda rights and that the boy had already implicated himself. For him, Santana and the other four were in Central Park attacking people and involved with what happened to Meili.

When Reyes came forward, Sheehan wondered why no detectives on the case had been interviewed. Sheehan had actually helped put Reyes behind bars for the murder of Lourdes Gonzalez in 1989 and knew how dangerous he could be, but in the case of Meili, Sheehan believes it was a gang, not one man, who assaulted her.

“It’s really disheartening and disgraceful,” Sheehan said. “Anyone who is out there saying that they’re innocent and believing them, shame on them.”

WHERE IS HE NOW?: Sheehan retired from the NYPD in 1993 and went on to become a reporter for New York’s WNYW, but was fired from the station in 2009 after he was arrested himself for DWI and refusing to take a Breathalyzer test after driving his car into an NYPD horse. He was charged with reckless endangerment and operating a vehicle while intoxicated and impaired.

Sheehan denied the charges and claimed the horse hit him and later became a reporter for WPIX-TV.

Justice Thomas Galligan, Manhattan Supreme Court Judge

WHAT HE DID: Defense lawyers were ambivalent about the selection of the trial judge from the start, but they were lucky that Justice Thomas Galligan, who had a reputation for harsh sentences, was randomly picked for this case.

”Judge Galligan has a law-and-order image,” defense attorney Cory Moore told the Times at the beginning of the trial. ”I don’t think anyone has been acquitted in his court in the last two years.”

Even though police detectives and prosecutors investigating the case insist that they made sure parents were present when the youths were interrogated, the judge said it wasn’t necessary, which challenged defense lawyers’ assertions that parents were required to be present when minors are questioned.

The prosecution’s case was heavy and strong. They had the support of people from every racial background and political backing of the entire city when a jury found the five guilty in 1990 after two separate trials. When sentencing Salaam, McCray and Santana, Galligan called them “mindless marauders seeking a thrill,” and said that Central Park had been turned into a “torture chamber.”

“The intensity of the violence that occurred is something no rational mind can explain,” he said during the sentencing hearing in which they were sentenced to 5 to 10 years in a juvenile facility. “The defendants showed no remorse, only defiance.”

Richardson and Wise were sentenced in a separate trial to 5 to 10 years and 5 to 15 years, respectively. Wise was the only one of the group that went to adult prisons having been arrested at 16.

Ironically, Galligan was also the trial judge in the murder and rape case of Reyes, whose admission overturned the conviction of the Central Park Five.

WHERE IS HE NOW?: Galligan continued on the Manhattan Supreme Court bench until his retirement in the mid-1990s. According to an online obituary, he died in 2015 at the age of 90.

Nancy Ryan, Assistant District Attorney

WHAT SHE DID:Initially, Nancy Ryan was the prosecutor assigned to the Central Park Jogger case because Trisha Meili was expected to die from her injuries, according to reports. In fact, she was so badly injured, she was given last rites. After it was concluded that she would survive, the case was taken over by Fairstein’s Sex Crimes Unit, and Lederer was placed in the lead.

In a turn of events, Ryan still became a determining factor in exonerating the Central Park Five.

When Matias Reyes confessed that he and he alone was responsible for what happened to Meili, it sent Morganthau’s office in a new direction to see if this had in fact been a master class in railroading.

A 2002, a probe was finally opened into the case. Despite what investigators and prosecutors considered confessions, the DNA matched Reyes, and none of the five who were convicted of Meili’s assault. In a 58-page document that reads first as a review of the case and then as a graphic depiction of the rape, Ryan asserts that Reyes, who was already serving 33 ¹⁄³ years for a separate rape and murder, was ultimately guilty rather than the five youths.

According to the court motion:

“Reyes’ 1991 prosecutions had rested in part on DNA evidence taken from his victims and from the scenes of his crimes, which matched the DNA in a sample taken from him. That evidence had been tested using the technology then in existence, RFLP, as were the samples in the Central Park jogger case. Immediately upon learning of Reyes’ claims, efforts were undertaken to locate the evidence from both cases, and the FBI laboratories were asked to make a comparison. On May 8, 2002, the District Attorney’s Office was notified that Reyes’ DNA matched the DNA taken from the sock that had been found at the Central Park crime scene.”

The Manhattan D.A.’s office, seeing the new evidence vacated the convictions, exonerating all five.

WHERE IS SHE NOW?: Ryan moved on to head the office’s trial division and stayed at its helm for 20 years, according to the New York Times. Once Morganthau retired, his successor, Cyrus Vance put a new attorney, Karen Friedman Agnifilo in her place.

“I’ve been here a very long time,” Ryan said of her 2010 departure from the office. “I think that I’ve accomplished a great deal. With a new administration in place, it just seems like a natural time for me to make a transition to something else.”

Since that time, she’s been a criminal justice consultant for Prisoners Legal Services of New York. She, like Lederer, has not spoken publicly about the case.

Madison J. Gray is a contributing editor for theGrio.com. He has written in the past on issues of justice in urban America, including cases like the Central Park Five, whose members he interviewed in 2013. He also interviewed Raymond Santana for theGrio last year. Follow him on Twitter @mjgraymedia.

[ad_2]

Source link