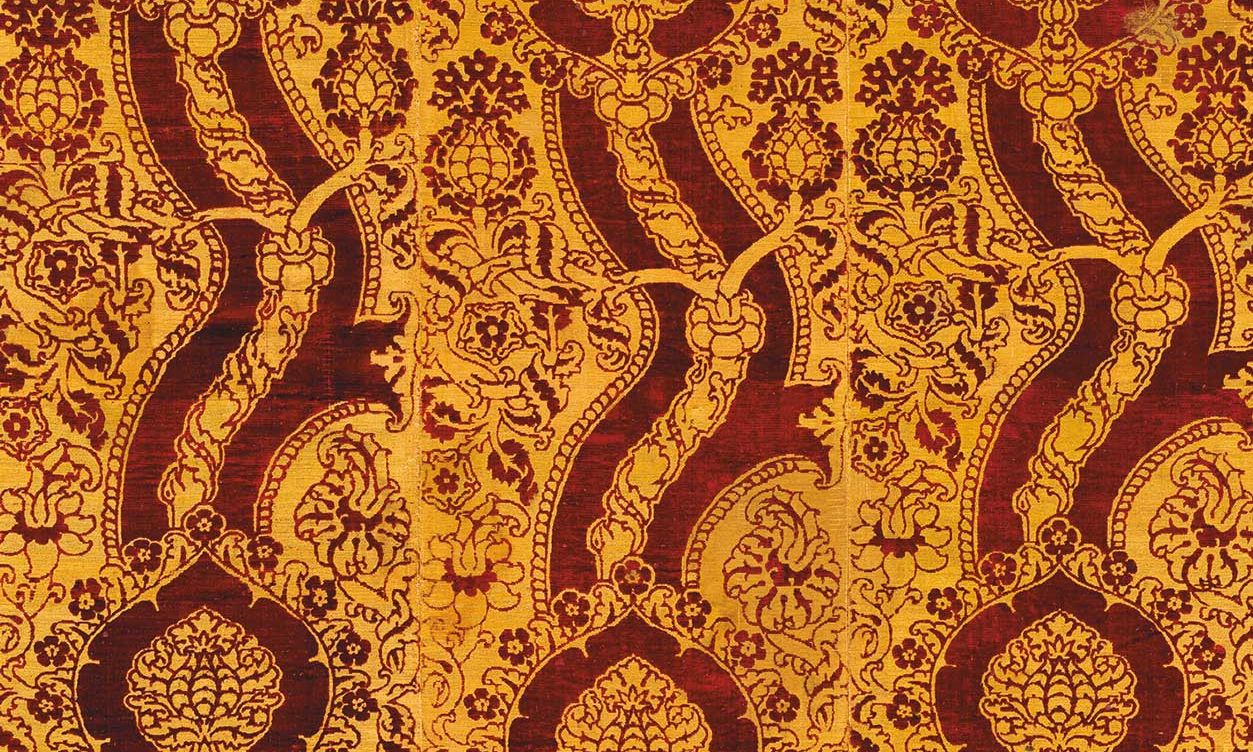

Furnishing textile (late 15th to mid 16th century),the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Could this really be the inspiration for Henry VII’s Tudor Rose? © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Tudor monarchs have exerted a fascination over publishers and film/television production companies in search of a guaranteed audience. With the successful run of The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and its recent opening at the Cleveland Museum of Art (until 14 May), it seems an appropriate moment to ask: is there anything more to say about the Tudors?

The accompanying catalogue consists of nine chapters, interspersed with entries for the objects included in the exhibition’s various iterations (at three venues). The scale of the Met curators’ Elizabeth Cleland and Adam Eaker endeavour is magnificently apparent in a publication that does the visual and material dimensions of its subject justice. Anyone interested in the Tudors will want to own this book, but whether it will prompt further research is less straightforward.

The essays and entries focus on the connections between decorative and visual arts, and their deployment by the Tudor monarchs as a means towards legitimising and consolidating their authority. This will not come as news to anyone even faintly aware of the success of Tudor royal propaganda and their habit of emblazoning buildings with their emblems, and the promise of unity and stability (after the 15th-century civil Wars of the Roses) conveyed by the dynastic motif of the union Tudor

rose. More surprising is the extent of activity within Europe, with a range of less familiar objects here juxtaposed with immediately recognisable images, such as Quentin Metsys the Younger’s The Sieve Portrait of Elizabeth I and Holbein’s luminous images of Henry VIII’s court.

One highly unusual object discussed is an embroidered portrait of Elizabeth I (Cat. No. 65), combining painted vellum for the queen’s face and hands with intricate embroidery using silk, spangles, pearls, gold, silver threads and human hair for the queen, an apparently unique and “remarkable survival”. In such objects we catch a glimpse of a luxurious material environment that represents a tiny percentage of the riches that once adorned the Tudor court.

We also gain insights into the practical dimensions of supplying so much grandeur, thinking about the ways in which designs for stained glass windows in King’s College Chapel, Cambridge moved from Dirck Vellert’s Antwerp studio to production in a workshop in Southwark, London and then via water to Cambridge (Cat. No. 18). The London goldsmith Affabel Partridge is traced through his hallmark of a bird (Cat. Nos 40, 60, 61) and the possibility that he may have been host to Lady Jane Grey during her short stay in the Tower prior to her execution in 1554. Recent research is brought to bear in the discussion of the portrait of a young woman from the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, once thought to portray Katherine of Aragon, but now reidentified as Mary Tudor, later Queen of France and Duchess of Suffolk (Cat. No. 13).

Another fresh insight and eye-catching interpretation focuses on a late 15th- to early 16th-century velvet cloth of gold furnishing textile. In her chapter, England, Europe, and the World: Art as Policy, Cleland writes it is “tempting to hypothesise” that Henry VII adapted the design to create his device of the Tudor rose. The idea is intriguing, though some further investigation of the references given reflects the difficulty of achieving certainty. (It is regrettable that the Met’s online catalogue moves to present the hypothesis as fact.)

Nicholas Hilliard’s The Heneage Jewel (around 1595-1600), a tribute to Elizabeth I as sovereign and supreme governor of the Church of England

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

No bibliography can be comprehensive (this one stretches to 23 pages), but there are some surprising omissions: no mention of Claire Gapper’s work on plasterwork, Tara Hamling and Catherine Richardson’s studies of material culture, Nigel Llewellyn on funeral monuments, or Matthew Dimmock’s spectacular study of Elizabethan Globalism (Yale 2019). Indeed, the global dimension of the Tudor world is not considered at any length, with only brief hints of a larger subject via entries relating to imported objects featuring Indian mother of pearl and Chinese porcelain. It is surprising to find Neville Williams’s books on the Tudors and their courts cited, but not more substantive works of court and political history.

It is also remarkable to find a publication on the Tudors and their courts which contains so few references to the politics of the period. This could be taken as a virtue, avoiding yet another review of the travails of Henry VIII in search of a fertile wife or the precise bodily status of Elizabeth I. Yet the distinctions that still exist between studies of people and politics, literature and art, architecture and the material world of the court, and connections with Europe and the wider world, remain to be fully overcome. Perhaps the task of bringing together these strands of analysis might prompt a new direction in Tudor studies, to be achieved through collaborative scholarship.

So although this book offers worthwhile insights into the Tudors, not just as an extraordinary elite dynasty but as monarchs who presided over a remarkable era in art, design and cross-cultural influences, there remains scope to say much more about their world and the people who lived within it.