[ad_1]

©ARTNEWS

Many have taken up the task of unearthing the Mona Lisa’s secrets over the years—including Salvador Dalí, who, in the March 1963 issue of ARTnews, tried to grasp the painting’s mystique by way of Freudian analysis. With Leonardo da Vinci still high in mind after the sale of Salvator Mundi for $450.3 million in 2017 and a major retrospective coming to the Louvre in Paris in October, ARTnews turned for a fresh interpretation of Dalí’s decades-old article to Martin Kemp, the author of Leonardo by Leonardo (Callaway Arts & Entertainment, 2019) and one of the foremost experts on the enigmatic Renaissance star. “Very lively, very punchy,” Kemp remarked about the article. “Do I take it seriously as a historical contribution to Leonardo? That’s another matter.” Dalí’s full essay can be found here.

Below are Kemp’s thoughts on some of Dalí’s musings…

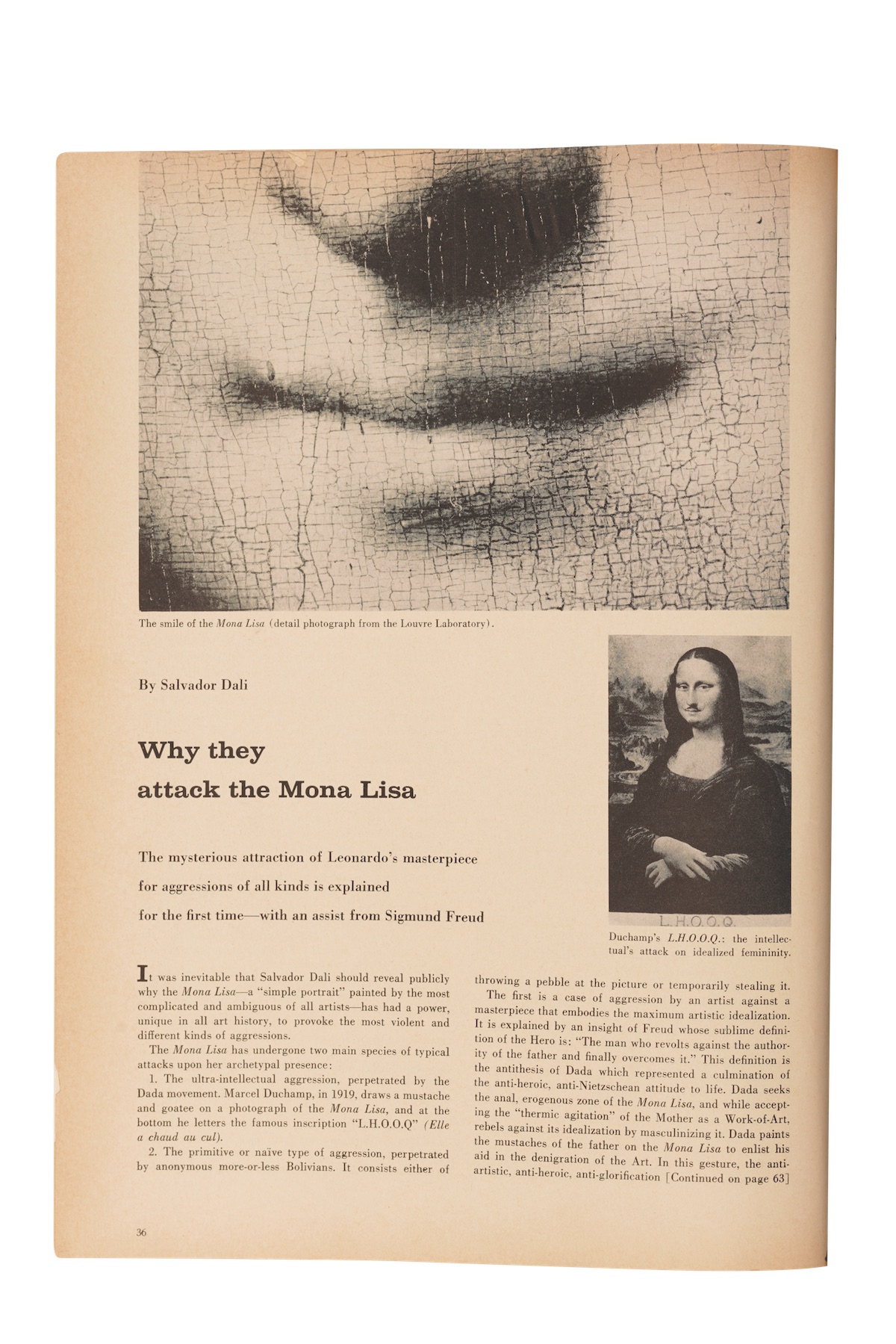

…aggression by an artist against a masterpiece that embodies the maximum artistic idealization. It is explained by an insight of Freud whose sublime definition of the Hero is: “The man who revolts against the authority of the father and finally overcomes it.”

Putting a historical figure on the psychologist’s couch is problematic because historical records always [preserve] certain things and not others. In the case of Leonardo, if we look at the thousands of pages of his notes, there’s very little that lets his guard slip.

Dada paints the mustaches of the father on the Mona Lisa to enlist his aid in the denigration of the Art. In this gesture, the anti-artistic, anti-heroic, anti-glorification and anti-sublime aspects of Dada, epitomized.

Great things tend to evoke attacks. It’s a way of somebody making their mark. Celebrity culture—the other side of that is anti-celebrity culture. Salvator Mundi was sold by Christie’s as a celebrity picture, and that evoked a reaction, which has nothing to do with what the picture looks like. Celebrity culture affects the current view of the Mona Lisa—she’s the ultimate historical celebrity.

To explain the “naïve aggressions” against the Mona Lisa, bearing in mind Freud’s revelation of Leonardo’s libido and subconscious erotic fantasies about his own mother, we need the genius of Michelangelo Antonioni (unique in the history of cinema) to film the following sequence: A simple naïve son, subconsciously in love with his mother, ravaged by the Oedipus complex, visits a museum.

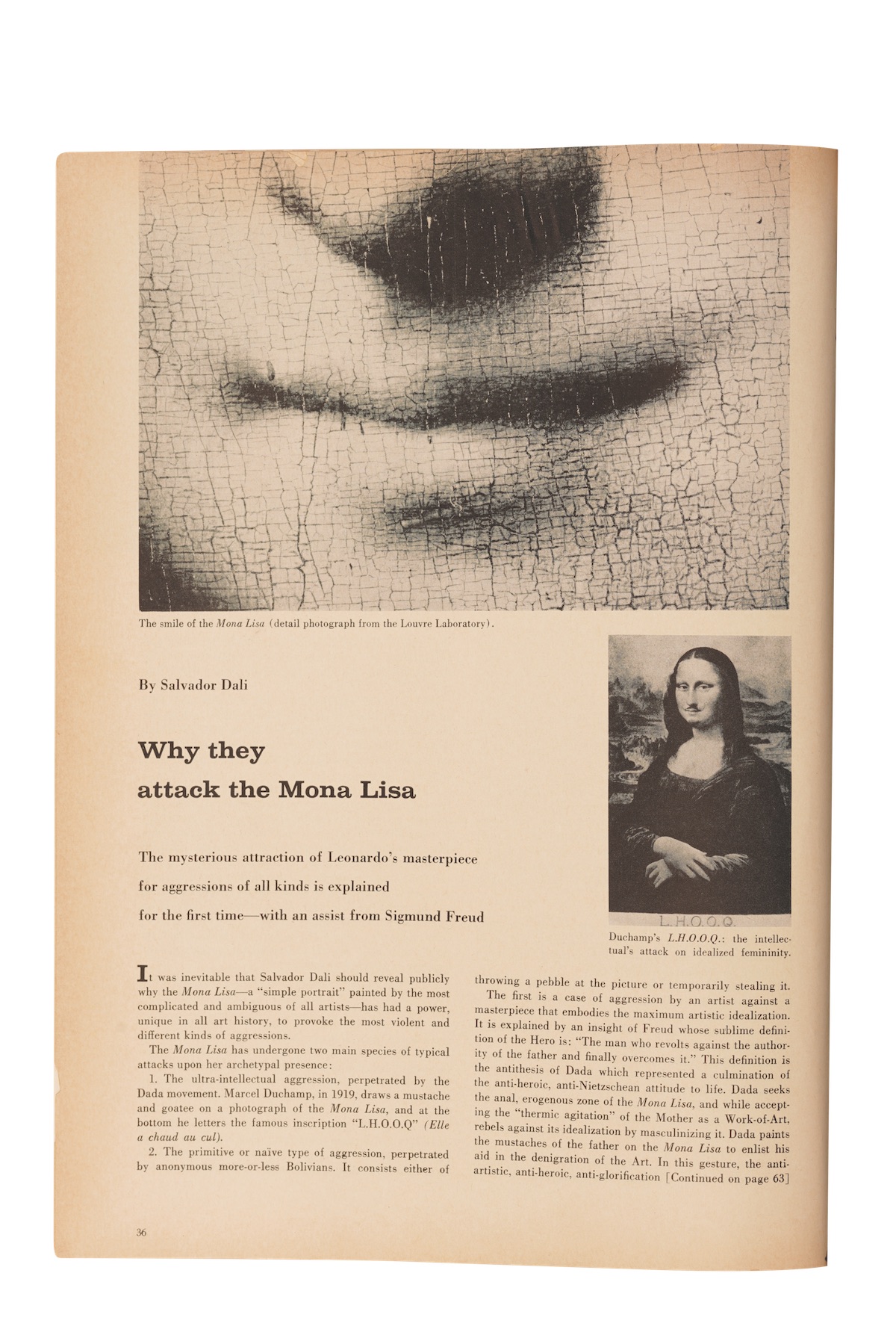

The standard way [of making female portraits during Leonardo’s time] was to portray women in profile. It was psychologically reticent. Leonardo broke that. He is probably the first artist to leave the spectator to complete the work and invite the spectator in, but he doesn’t tell the spectator definitively what to look at. Mona Lisa not only looks at us, but she looks ambiguously—and she smiles. To have this woman presenting herself, turning to look at us and smiling, is very daring. It’s part of the invitation.

Anyone who can offer different explanations of the attacks suffered by the Mona Lisa should cast his first stone at me; I will pick it up and go on with my task of building the Truth.

As someone who’s dealt with Leonardo for 50 years, I relish the range and variety he attracts. [Dalí’s ideas] aren’t irrelevant. Leonardo issues an invitation to the spectator, and Dalí accepts the invitation. Dalí also issues invitations to the spectator—to access unconscious minds and come to terms with the strange plural images he creates. You can see why he’s attracted to works of art that have an enigmatic quality.

[ad_2]

Source link