[ad_1]

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) was one of the deftest documentarians of African-American life in the United States, and over the next few years, people across the country will get a chance to see one of his greatest series of paintings, “Struggle: From the History of the American People” (1954–56), united in full for the first time. With the series’ nationwide tour kicking off at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, earlier this month, ARTnews pulled from deep in our archives a 1944 profile of Lawrence by Aline B. Louchheim. Leslie King-Hammond, founding director of the Center of Race and Culture at the Maryland Institute College of Art and an expert on Lawrence, was enlisted for a contemporary insight on a piece that, today, reads as dated. “Like many critics at the time,” King-Hammond said of Louchheim, “the author had very little knowledge of the African-American experience.” Louchheim’s full profile can be found here.

Below are King-Hammond’s thoughts on Louchheim’s profile of Lawrence.

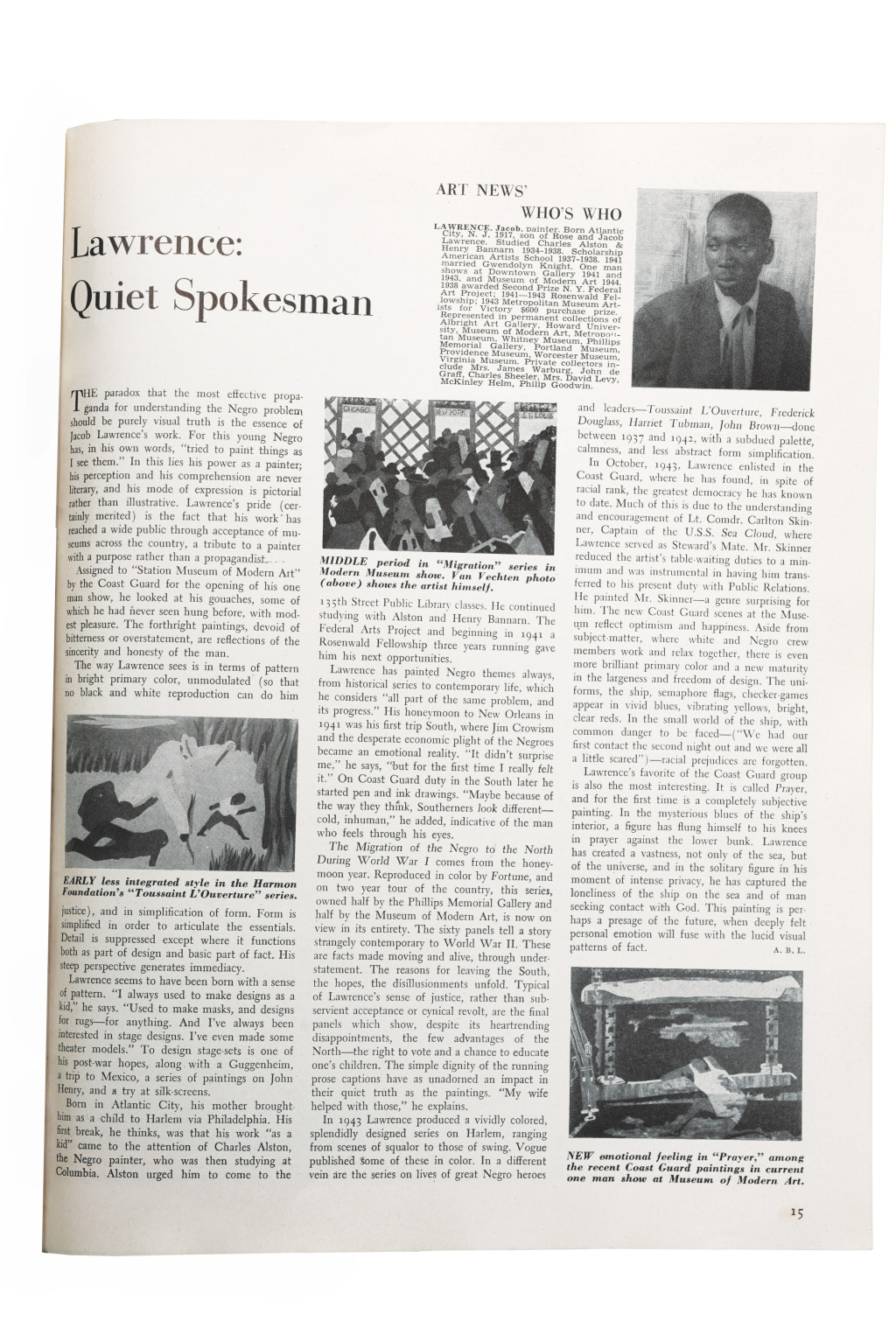

The paradox that the most effective propaganda for understanding the Negro problem should be visual truth is the essence of Jacob Lawrence’s work. For this young Negro has, in his own words, “tried to paint things as I see them.”

I don’t think he was doing propaganda! I think he was just responding to a very personal, very real experience in his time, using references from direct subject matter. He created imagery out of themes that were, by the standards of the time and of what other modernists were focusing on, so astute. He took the ordinary, the mundane, the commonplace—he took all these elements of humanity that most people did not want to pay attention to, in certain circles, and he elevated them in a way that was shocking. [Louchheim] kind of got woke—she said, “Look at these images, these stories, these people! Oh, my God!”

The way Lawrence sees is in terms of pattern in bright primary color, unmodulated (so that no black and white reproduction can do him justice), and in simplification of form. Form is simplified in order to articulate the essentials.

At the time, there was a big question in the artistic mind of many African-American artists: whether to go “modern.” Somehow, I don’t think that was a conversation that created a climate for Jacob Lawrence, but he decided to tell stories without personalizing his style, meaning that he did not get into figurative details and portraiture as we came to know it at that point in history.

The sixty panels [in “The Migration Series,” a 1940–41 group of paintings about the Great Migration] tell a story strangely contemporary to World War II . . . The simple dignity of the running prose captions have as unadorned an impact in their quiet truth as the paintings. “My wife helped with those,” he explains.

We cannot discount the impact of his wife, Gwendolyn Knight, who was also a painter and very much in support of his work. . . . [Knight was] not just a housewife. She wasn’t just sitting there, cooking and making sandwiches. She was an artist, and she was helping him create all the narrative panels of this work.

In October, 1943, Lawrence enlisted in the Coast Guard, where he has found, in spite of racial rank, the greatest democracy he has known to date.

After the Coast Guard, he went to a sanitarium because he was having some emotional issues, like all people. Jacob took some time out, to seek therapy, but what did he do? He painted! He didn’t stop recording those experiences. Everything was a muse to him.

[ad_2]

Source link