[ad_1]

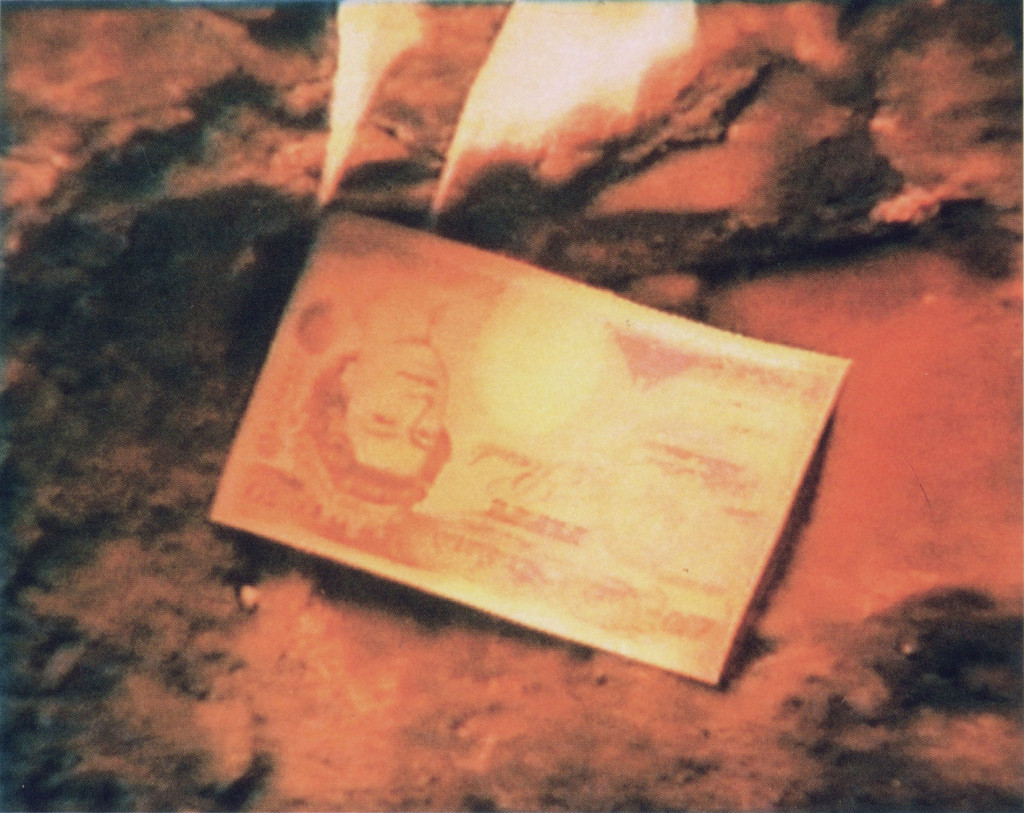

As a camera rolled on a dark night on the Scottish island of Jura in August 1994, artists Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty passed a whiskey bottle back and forth while tossing £1 million into a roaring fire. The sum—more than $1.5 million at the time—was most of what they had earned as the hit music group KLF, and they were making a film. After about an hour, every bill (each a £50 note) was destroyed.

“We wanted the money,” Drummond told a crowd assembled for a TV talk show a year later, “but we wanted to burn it more.” Most of the audience members who lobbed questions at the duo were exasperated. Why didn’t they just give the money to charity? Why didn’t they do something useful with it? What was wrong with them?

The duo, who rechristened themselves the K Foundation, weren’t the first to relinquish wealth in the name of art. Some three decades earlier, French trailblazer Yves Klein stood by the Seine in Paris and sold what he termed Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility—a decidedly ephemeral work that could be acquired for a sum of gold. Once the bullion was handed over, Klein wrote a receipt, promptly burned it, and tossed half the gold into the water. Voilà!

Such displays of outrage and absurd daring anticipated the instantly infamous $120,000 banana deployed by Maurizio Cattelan at Art Basel Miami Beach last December. This time, condemnation streamed from bewildered media entities and internet commenters. In an era of gaping wealth inequality, environmental degradation, and political strife, how could anyone spend that much money (and even more, as certain of the works in an edition were said to sell for $150,000) for a banana? Also: what kind of fraud of a person would make such a thing?

Rhona Wise/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

It’s tough out there for artists! Burn all your hard-earned money, and people get upset. Mint a small fortune through a clever gimmick, and the results are the same. But never mind. The burning bills, the sunken gold, and the immodestly priced banana are just three particularly extreme examples of a mode of art at least a century old that takes money as its medium—literally or figuratively.

Call it Money Art.

In 1939, critic Clement Greenberg argued that the avant-garde was connected to the ruling class of society by an “umbilical cord of gold.” Money Art often focuses on that cord with a gimlet eye. In a time defined by the commodification of art—recently minted paintings showing up on the auction block, seven-figure prices for artists barely 30 years old—Money Art questions the churning operation of the art industry. It harnesses streams of cash for new ends and lets viewers see finance operating with often startling clarity.

Damien Hirst’s diamond-bedecked skull, For the Love of God (2007), is classic Money Art, since its price tag—a cool £50 million, or about $100 million at the time—is a key component of the piece. (Not to mention its markup from the reported £12 million spent to make it.) Richard Prince’s more aggressively appropriative works—like those reproducing with only minor alterations the work of professional photographers—also count, given that part of their menacing appeal owes to the looming sense that they are backed by a willingness to litigate at length (another form of burning money). So, too, are certain new cost-intensive sculptures by Jeff Koons, whose financial structures—as documented in recent lawsuits—have the intricacy of real estate deals.

Prudence Cuming/Scienceltd/Whitecube/Shutterstock

While the more splashy, crass works of Money Art grab headlines, a whole secret history of 20th-century art can be written about more nuanced and oblique approaches to the form. These are works that consider and challenge the ways that money operates in contemporary society as a source and symbol of power and shame, and as a tool for exchange.

Money Art can take the form of radical, vulnerable exposure. From 2011 to 2013, the artist Kenya (Robinson) aimed to record what an accompanying text called her “two-year experience as a black MFA student at Yale University while struggling to maintain her personal finances and secure fiscal support,” by posting her bank balance online every day. The numbers usually hovered in the three digits and occasionally slid into negative territory. As the numbers appeared, the work took the form of a portrait of someone barely getting by—a subject also addressed by Occupy Museums in its recent studies of student debt in the United States.

(Robinson)’s harrowing piece harkened back to Full Financial Disclosure, a 1977 classic by a midcareer, post-performance Chris Burden. As a small pamphlet he published detailing his expenses and income in 1976 explained, “In keeping with the Bicentennial spirit, the post-Watergate mood, and the new atmosphere on Capitol Hill, Chris Burden wishes to be the first artist to publicly make a full financial disclosure.” Burden’s total profit for that year was $1,054—about $4,470 today—a modest sum for a figure so established in art history.

©Chris Burden Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Beyond their larger political implications, the undertones of such work are stark: surviving solely as an artist in the United States is a deeply difficult business. As music producer Steve Albini put it in a 1990s-era essay on who does and does not get paid in the record industry: “Some of your friends are probably already this fucked.” This goes for many artists at work in all other mediums, even if they may not say so.

Artists have also gamely sought to expose the finances of the elite or redirect its flow. Andrea Fraser published 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics, a massive book that meticulously details the (often right-wing) political giving of board members at American museums. And for a worked featured in Documenta in 2017, Maria Eichhorn spent about $158,000 from Zurich’s Migros Museum on a building in Athens, Greece, which she has attempted to make legally unowned, carving out a new state of property.

Merlin Carpenter, an artist living in London, has made a side career out of toying with his compensation from supporters. For a 2011 show at MD 72 gallery in Berlin, he charged visitors €5,000 to see the works on view, a sum that could be deducted from a potential purchase. And in 2006, he convinced the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia to give him $4,000 in cash to create a work for a group show. As Carpenter’s website explains, “The artist then went on a wild shopping spree enjoying luxurious goods and services, with only the receipts and empty shopping bags exhibited.”

©Estate of Marcel Duchamp/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

As with movements of so many other kinds, Marcel Duchamp is a pillar of Money Art. For his 1924 work Monte Carlo Bond he advertised a series of bonds by which he claimed he would exploit a system he had developed to make money while at the roulette wheel in Monaco. The details of the enterprise are hazy, but he reported to friends that, over countless hours of spinning, “I’m neither ruined nor a millionaire and will never be either one or the other.” That’s about all that most artists hope for, at the end of the day.

Not all Money Art is wily or cynical in operation. It has also forged vital and inspiring philanthropic efforts. Mark Bradford and Theaster Gates, to name two examples, have made central to their practices their respective social-welfare and cultural organizations, Art+Practice in Los Angeles and the Rebuild Foundation in Chicago. They conceive of the artist not only as a maker of objects but also as a fundraiser and a force for change.

Money Art is as malleable and elusive as money itself, slipping into a panoply of practices, changing the way artworks operate in unseen ways. At its core, though, the genre operates on relationships between art and money, which are complicated, tortured, and very intimate.

The Greek-Belgian artist Danai Anesiadou recently vacuum-sealed a kilogram of gold in plastic for another work at Documenta. Valued at around $40,800 in late 2017, the precious metal is now, two years later, worth about $58,000. That’s not a bad return, and it certainly offers a new twist on Andy Warhol’s old quip that, if you’re going to buy a $200,000 painting, “you should take that money, tie it up, and hang it on the wall. Then when someone visited you, the first thing they would see is the money on the wall.”

©Estate of Nancy Reddin Kienholz/Courtesy L.A. Louver, Venice, California

At its most political edge, Money Art questions how wealth is dispersed in society, and how the art market operates. In its most vicious forms—the burning £1 million, say—it recalls a famous scene in the 1985 screwball comedy Brewster’s Millions in which the eccentric millionaire Rupert Horn informs Monty Brewster (Richard Pryor) that, in order to inherit $300 million, he first needs to spend $30 million without having anything to show for it. “I’m going to make you so sick of spending money,” the millionaire says, “that the mere sight of it will make you want to throw up!”

And yet, there is often a deep playfulness to work that fits into the genre, a wry wit. That sensibility was exemplified in 1969 by Edward Kienholz’s beginning a series of essentially identical watercolor paintings bearing widely different prices (For $87, For $878), in a way that foregrounds the arbitrary pricing of art. It was also present in 1983 when Louise Lawler produced an edition of gift certificates for the Leo Castelli Gallery—an artwork literally doubling as a financial instrument that gave its owner a tough choice: save the artwork or cash it in for something else.

At its best, such work shrugs off any pat or easy explanation, as does all great art. Drummond, one of those who burned the KLF fortune back in 1994, offered a variety of explanations for the pyre of money in that TV interview, but even as he discussed the decision articulately, any precise answer seemed to elude him. Why do it? “There was a lot of reasons why,” he said, “and we’re still discovering the reasons every day.”

A version of this article appears in the Spring 2020 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Hard Cash.”

[ad_2]

Source link