[ad_1]

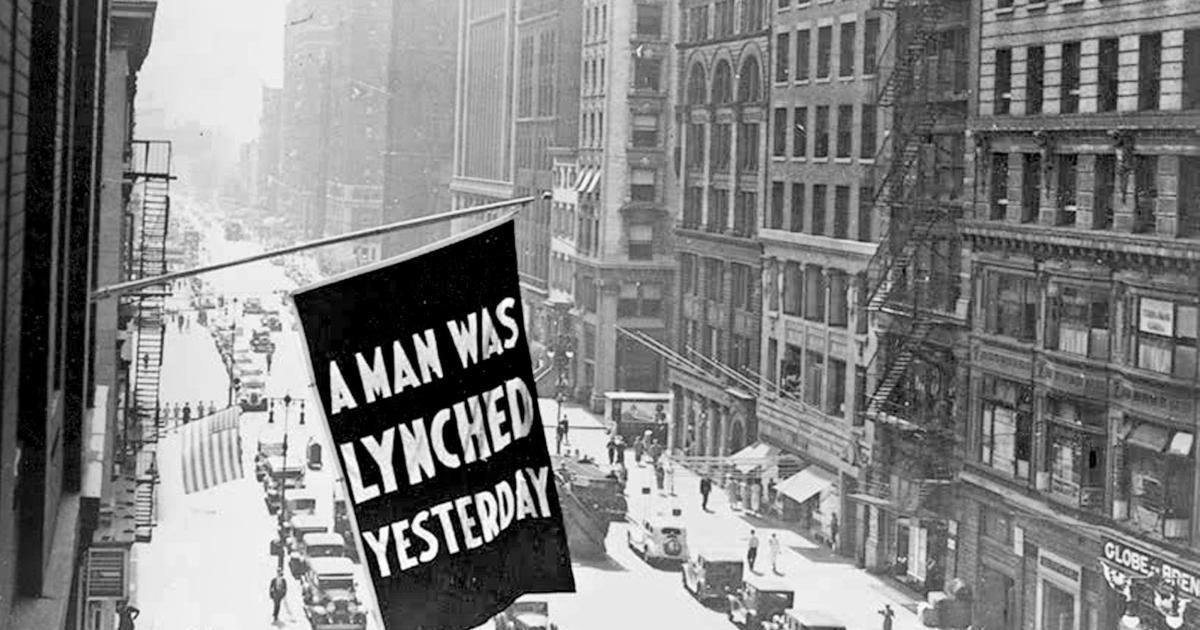

The first country-wide memorial to African-American victims of lynching opened last year in downtown Montgomery, Alabama.

While it’s called the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the site is not government funded. It was built by the Equal Justice Initiative, a legal nonprofit that defends against wrongful convictions and racial discrimination.

At the center of its six-acres is an open-air pavilion with 800 hanging steel columns. Each represents a county where a lynching took place and is engraved with the names of the victims. In total, the memorial lists more than 4,000 names touching 20 different states.

Looking through the names of the victims, you can get the impression that they all represent stories that have been well documented and investigated. But that’s not exactly true.

It wasn’t in Finch’s case.

On my first visit to the memorial a year ago, I saw him listed on the column for Fulton County. It’s after the dozens of victims of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. That name is a misnomer for what was a massacre of black residents by a white mob.

Finch’s name is near the end. He died on Sept. 12, 1936, in the center of Atlanta. His is the last lynching listed for the city.

[ad_2]

Source link