[ad_1]

El Anatsui, Second Wave, 2019, installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich.

JENS WEBER

The weight of institutional politics hangs over a retrospective for the Ghanaian sculptor El Antsui at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. Over the past couple years, there has been controversy surrounding the circumstances of Okwui Enwezor’s departure as director of the Haus der Kunst in 2018 and the subsequent cancelation of major Joan Jonas and Adrian Piper retrospectives amid allegations of financial mismanagement. (The controversies might have been less conspicuous, had an exhibition by a septuagenarian, white, male German painter—Markus Lüpertz—not been lined up in their stead.) This time of change is hinted at in a new work Anatsui made for the show, the 361-foot-long installation Second Wave (2019). The work clasps the front of Paul Ludwig Troost’s building, which was first opened by Adolf Hitler in 1937 as a temple to German national art and has since become a global destination for the contemporary-art exhibitions hosted there. Anatsui’s structure resembles scaffolding, and its arrangement of printers’ plates gives it a papier mâché–like appearance. The work suggests that the Haus der Kunst is undergoing an Umbau, or a remodeling.

As with all of Anatsui’s monumental works, in spite of its grand scale, Second Wave is a delicate structure. Plates no thicker than card are held together with tiny rivets and buckle to the touch. The materials, as well as the dialogues between communities they reference, are at once fragile and robust: German corporate directories and images of soccer players enter into dialogues with Italian-language art magazines and posters advertising prayer meetings in Nsukka, Nigeria, where Anatsui lives and works. One such poster reads, “The Difference is in the Detail.”

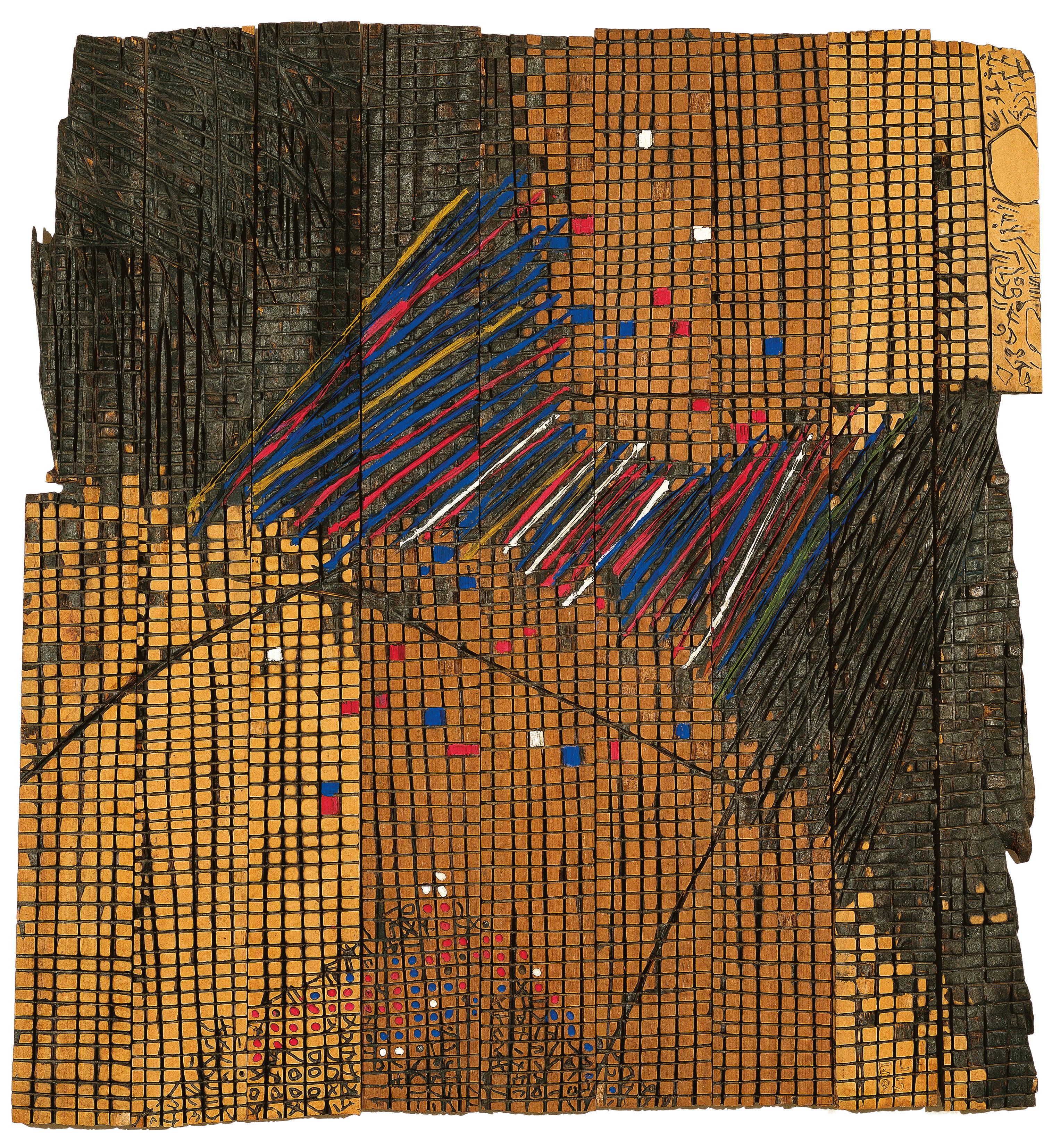

El Anatsui, Earth-Moon Connexions, 1993, wood, tempera.

SMITHSONIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN ART, WASHINGTON, D.C.

Curated by Enwezor, who died earlier this year, and Chika Okeke-Agulu, an art history professor at Princeton University in New Jersey, this retrospective—the largest one ever devoted to Anatsui’s work, and Enwezor’s final exhibition—makes visible the rootedness of Anatsui’s processes and materials in place. It showcases Anatsui’s rejection of the Western art forms he was taught using imported materials at Kumasi College of Art in Ghana. In search of a more sustainable practice using indigenous forms and materials, he began embellishing wooden trays used by local market sellers in Ghana, and later, in Nigeria, bonding broken pots using manganese and clay. This aspect of Anatsui’s work is well-known, but at the Haus der Kunst, which must now reevaluate its place in the global art world, the artist’s commitment to salvaging indigenous styles and art-forms—many of them either lost or at risk of disappearing—takes on new significance.

[Read a 2008 profile of El Anatsui.]

The legacies of colonialism and modernism are frequent reference points in Anatsui’s work. During the 1990s, in his wood panel works, Anatsui examined the violent carving up of Africa by Western countries, creating sculptures that feel both mystical and disturbing. One work in the show, Earth-Moon Connexions (1993), has been carved with a chainsaw, burned with a blowtorch, and colored with tempera, and presents both as a board game and a tactical battle plan. Divided and scarred like scorched earth, the gridded work includes local scripts that appear at its margins, far from its disturbed center. Likewise, there is Invitation to History (1998), which is both mournful and optimistic: bright colors peek through the overlaid grid, which is written over in the deeper grooves of West African languages.

El Anatsui, Stressed World, 2011, aluminum and copper wire.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND JACK SHAINMAN GALLERY, NEW YORK

Anatsui’s most famous pieces—vast, shimmering works crafted from bottlecaps that the artist has been making since 2000—likewise render the effects of violent histories in abstract terms. The materials used in these works foreground the Triangle Trade, through which goods were exchanged, often by force, between Europe, Africa and the Americas during the time of slavery. Rum from the West Indies was brought to Europe and sold in Africa, and peoples living on the continent were sold in the West Indies, so that sugar cane could be harvested and rum could be produced. These bright, aluminum tapestries resemble oceans, or continents or countries studded with metropoles. Often, as with Man’s Cloth (2001), its title a reference to Ghanaian Kente fabric, Anatsui’s works read as armor, with elements suggesting the regimented colors of national flags and military service ribbons. Ragged at the edges, works like Man’s Cloth are meditations on masculinity, tribalism, and conflict, and their impacts across cultures and time.

El Anatsui, Logoligi Logarithm, 2019, installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich.

MAXIMILIAN GEUTER

The significance of the materials chosen for Anatsui’s beautiful sculptures are illuminated by viscerally poetic titles. For Strips of Earth’s Skin (2008), Anatsui strung elements together such that they look like ammo belts, and worked bottle caps hang in ragged strips as if peeled from bodies, exposing the ecocide and genocide driven by the extraction of precious resources.

The amount of labor put into making these works is palpable, particularly in Logoligi Logarithm (2019), a maze of 65 screens suspended from different heights. Made from ring seals, the installation evokes the sails of a ship, camouflage nets, and the wings of a theatre all at once. It effortlessly conveys the allure of colonial adventure, the violence it wrought, and the illusions that sustained it. Extraordinarily, therefore, moving through it feels like being wrapped in an embrace and a calling down of ancestors. The title references a poem by Atukwei Okai—a friend of Anatsui who died last year—dedicated to the son of a friend who died young. The poem invokes heroes of independence movements in Ghana and elsewhere, as well as Frantz Fanon, Bob Dylan, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

The focus on Anatsui’s vested interest in languages, belief systems, and styles independent of the Western canon is a triumph of this exhibition, given that the discourse surrounding the artist’s work so often fixates on the scale, formal skill and references to global consumerism in Anatsui’s art—aspects more palatable to European and American audiences. It is a fitting send-off for Enwezor, who spent a career spotlighting non-Western creators on their own terms and shaping a truly global contemporary art discourse. The question now becomes: Will Enwezor’s legacy at the Haus der Kunst be allowed to continue?

[ad_2]

Source link