[ad_1]

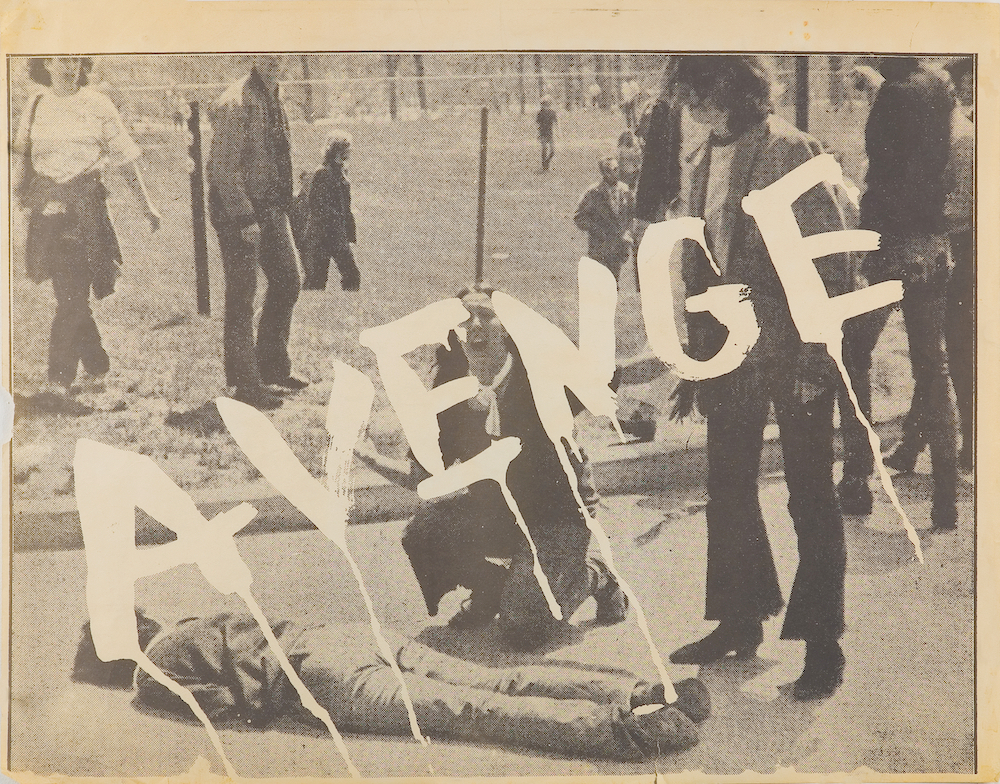

According to eyewitnesses, sergeant Myron Pryor was the first person to fire at the crowds of unarmed protesters at Kent State University in Ohio, around half past noon on May 4, 1970. Other National Guardsmen followed suit, killing four of the two thousand students gathered to denounce Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia (twenty-year-old Sandra Lee Scheuer wasn’t even protesting; she was on her way to class). Eleven days later, in the midst of a national student strike that closed more than 450 schools, police opened fire on student protestors at the historically Black Jackson State College in Mississippi, killing a seventeen-year-old from a nearby high school and a Jackson State junior. Marking the fiftieth anniversary of these killings, Interference Archive’s online exhibition “Walkout: A Brief History of Student Organizing” presents a selection of art and ephemera related to student movements. Drawn entirely from the volunteer-run Brooklyn organization’s collection, which is devoted to the history of activist art and cultural production, the show includes materials that date from the 1960s to the present, ranging from protest posters to punk zines to political memes.

In an introductory essay, the curators locate the birth of the student movement in the postwar period. The 1944 G.I. Bill dramatically expanded access to higher education in the United States, followed by a period of economic prosperity and a baby boom that tripled the student demographic, teeing up the American university as a staging ground for the radical ’60s. Organized by decade, the show offers a sense of student activists’ major concerns at different moments. Sections devoted to the 1960s and ‘70s are dominated by responses to the Vietnam War: students were horrified by the prospect of being drafted to fight and die in Vietnam, but they were also uneasy with the academy’s role in producing military intelligence and technology. The term “university-military complex” comes up repeatedly in a 1969 pamphlet called “How Harvard Rules,” which includes a flow chart illustrating the institution’s ties to warmongers and corporate profiteers. From the 1980s onward, a central preoccupation is educational austerity measures.

Much of the material consists of low-budget Xeroxed documents like newsletters or student publications, often accompanied by pen doodles and political cartoons. But there are pieces that stand out for their artistry, like “Is He Protecting You?” (1964), a poster produced by photographer Danny Lyon for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. It depicts a helmeted Mississippi state trooper against a blurry backdrop of white segregationists, with the titular phrase superimposed at his eye level, following his glance like a ballistic weapon. “End the Ugly Plastic War” (1970) is a transparent poster credited to UC Berkeley professor Jerrold Ballaine, for which he used a vacuum sealer to imprint the title on a vinyl sheet. Ballaine and his students originally designed the poster to be held aloft while protesting the bombing of Cambodia, but it is closer to Pop art, in its wry engagement with commercial aesthetics, than to typical protest graphics, standing in stark contrast to the proto-punk silkscreens of the French agitprop collective Atelier Populaire. Their iconic poster “Mai 68: Début d’une lutte prolongée” (May 68: the Beginning of a Prolonged Struggle), featuring the bright red silhouette of a factory flying a revolutionary flag, is reprised in Josh MacPhee’s 2018 Risograph print “University as Factory,” which Interference Archive gave out during May Day demonstrations that year. Atelier Populaire’s influence is also seen in Jesse Goldstein’s poster “Stop The Budget Cuts” (2012), used during strikes against tuition hikes at Québec universities. In the rudimentary single-color print, the fingers of a hand have been sliced off with scissors until only the middle one remains, accompanied by text reading: “There’s only one thing left to do: stop the budget cuts!”

Limited to a single archive’s collection, “Walkout” is more eclectic than comprehensive. Graphics and posters are frequently interspersed with text-heavy documents, interrupting the flow of the viewing experience, and the contextual information offered about the objects on view can be frustratingly inadequate: the 1980s section, for instance, includes only four items, one of which is an above-the-fold newspaper scan that cuts off all the articles, while the 2000s section includes a political meme in German with no English translation or explanation. As a result, the exhibition is not strictly useful as a record of how the aesthetics of student protest have developed over time. What it does offer is an enjoyable hour or two of clicking through history.

[ad_2]

Source link