[ad_1]

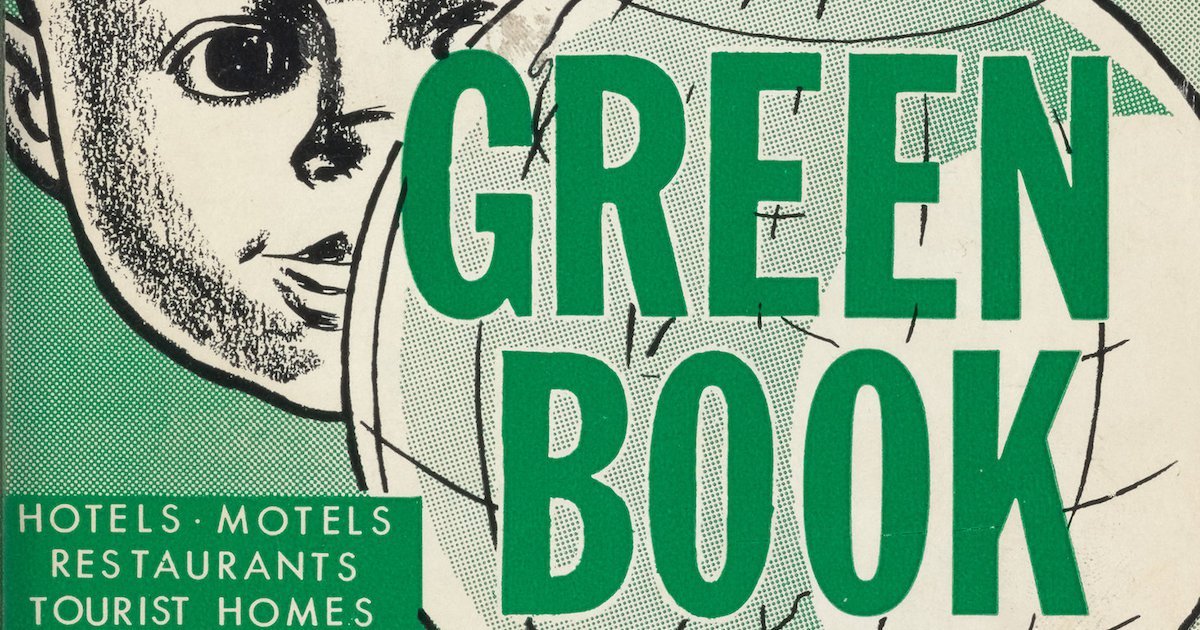

Next month, the actor Viggo Mortensen, one of the six cover subjects of T’s 2018 Greats issue, will star alongside Mahershala Ali in “Green Book,” a movie based on the true story of the jazz pianist Don Shirley’s road trip through the American South in 1962. Here, the author Kaitlyn Greenidge discusses “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” which served as a guide for black travelers across North America and inspired the film.

“How did you and Daddy meet?” I used to ask my mother. The answer always shifted — through friends, through the circle of black undergraduates in Boston-area colleges in the late 1960s. But once she said, “When we were children, his family knew there were black people who lived along the Concord Turnpike. They’d stop to see us on their way in and out of town. Everyone did it” — by “everyone” she meant black middle-class Bostonians — “they’d drive by to look at us while we played in the yard.”

That image — of black people in incongruous places, and the joy and pride we derive from encountering them — stuck with me for years. It was the inspiration for my first novel, “We Love You, Charlie Freeman” (2016). One of the characters, a black girl in 1940s Maine, becomes an object of fascination for black tourists. By the time I wrote that character, I had heard of the existence of the “Green Book,” a guide published between 1936 and 1967 that black motorists and vacationers could use as a resource to find which businesses, motels and towns would welcome them in a segregated United States. I was fascinated by this book, which included both black- and white-owned businesses. For every state, the “Green Book” attempted to list the hotels, barbershops, auto garages, restaurants and “tourist homes” that would accommodate black travelers. I found this last distinction intriguing — under it were listed “the parsonage of the AME church” sometimes, other times, for states like Idaho, only the address for a lone dude ranch. I couldn’t resist, so I included a fictionalized version of it for my character. She and her family were “an example of what was possible” as the “northernmost Negroes in the Continental United States” according to the “Colored Motorist’s Guide,” the title I used to stand in for the “Green Book.”

But first, she wants to show me her peonies. A few weeks before we meet, she emailed me a JPEG of a flower in full bloom, a still-life hello. Frothy white with a bright yellow center, it wasn’t just any peony, but the W.E.B. DuBois peony, which was named for the civil rights activist after Weems called up the American Peony Society with the suggestion. (As she tells it, they happened to have a new variety in need of a name.) The flower was to be the centerpiece of a memorial garden for DuBois at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst — a small but characteristically thoughtful gesture from an artist who has made her career creating spaces for contemplation in the place of absence, rooting a troubled present in a painful past with projects that feel resolutely forward-looking and idealistic.

[ad_2]

Source link