[ad_1]

The first rule of the Locked Room was that you didn’t talk about the Locked Room. The second was that you didn’t talk to each other, or remove any material from the room or document it in any way.

In September 1969, newly arrived first-year sculpture students at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London were handed name badges and a cube of polystyrene wrapped in brown paper, and ushered inside a bolted and padlocked room. Inside, they found their names pasted at distanced intervals on the floor, along with a list of rules. Students were told that they were not allowed to leave the room between 10 a.m. and 4:30 p.m., except to fetch tools, and were silently supervised by at least one professor at all times.

Technically, this was an art class. But it was also a pedagogical experiment that later came to be dubbed the Locked Room. It ran for two years and was the brainchild of tutors Garth Evans, Gareth Jones, Peter Kardia and Peter Harvey. Looked at today, it’s a bizarre footnote in the annals of art history that corresponds with coronavirus-era quarantining and surveilled forms of labor.

The project doesn’t have much of a legacy, and has only recently being re-evaluated, thanks to a 2019 exhibition at London’s Laure Genillard gallery and a new collection of interviews and ephemera The Locked Room: Four Years That Shook Art and Education, 1969–73 (published by the MIT Press), both from curator Rozemin Keshvani. But back then, it was meant as a project exploring how people might communicate with each other under controlled settings—and it may well have inspired shifts in art education and art-making.

Speaking to ARTnews, Evans related how the project sprung out of the tutors’ frustration with didactic models of teaching, the inefficacy of language, and “the incompatibility that exists between nude objects and words.

“That led to an idea,” Evans said. “Why don’t we give the students material stuff and nothing else? No instructions, and let them work with that.”

During the second week, students entered the room to find it emptied of everything they had been working on. The polystyrene was replaced by a roll of Kraft paper; a large ball of string, a bag of plaster, and, later, water were also supplied. They received no indication of how long they would have each material, apart from a stopwatch, and they were given no framework explaining the project’s intentions or duration. As the weeks bore on, there was no assessment or positive feedback from the experiment’s facilitators, either. Any new rules arrived in the form of writing, and students were verbally admonished only for tardiness or breaking a rule.

Locked Room was controversial in its time. Concerned for the students’ mental health, the school principal brought in a psychiatrist to evaluate the situation. But it’s possible that, beyond that scandal, it was an important forerunner to a kind of conceptual art being birthed in Europe at the time. One could even say that the project prefigured artist Joseph Beuys’s idea of the “social sculpture,” a kind of art that was shaped equally by its creator and the people who interact with it. There’s some evidence that the students even considered it a conceptual piece. During a 2010 Locked Room reunion conference, Evans said, he learned that some of the students implicitly understood the project as an artwork, although the staff did not conceive of it as such.

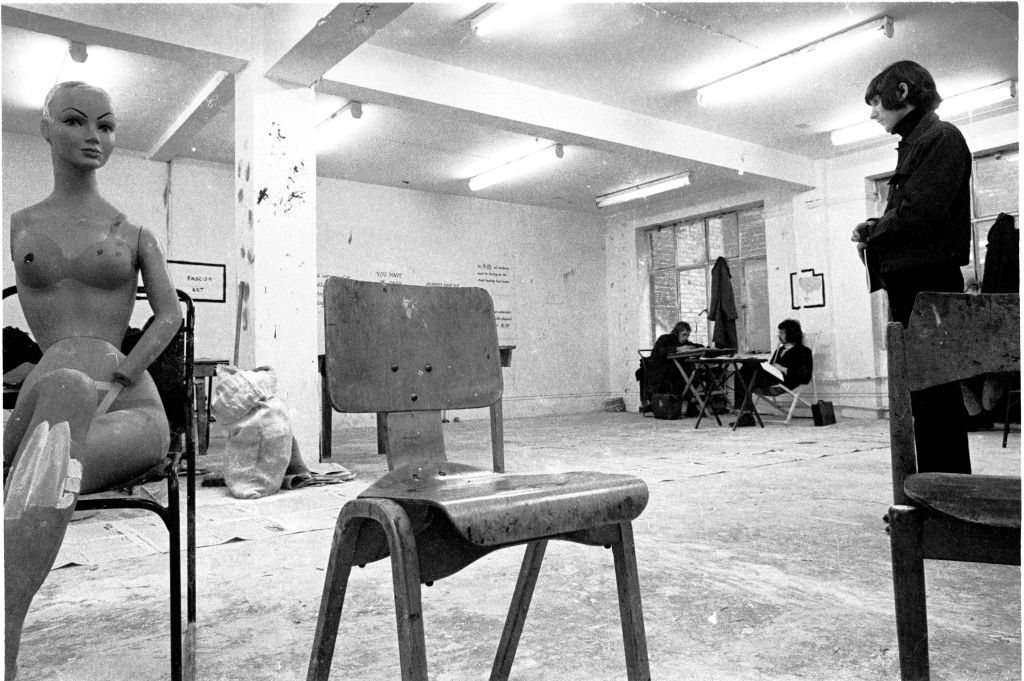

Courtesy Tony Hill

Evans wanted to work against the prevailing ethos in art schools at the time, which he described as being loose, unstructured, and unregulated. Soon after, the Coldstream reforms would dramatically overhaul British art education, moving it away from a skill-based system and creating standards to make it degree-equivalent. He also wanted to move away from a pedagogical model of transmission and replication to “find a role for myself in which I was not simply trying to get them to adopt my values and my worldview. The business of bringing something new into the world is truly difficult to contrive to facilitate.” And perhaps they succeeded: Evans related how, during the next year, other professors complained that “the way [the 1969 batch] had been taught during the first year had made the students unteachable. And if we were allowed to continue, the entire department would be full of unteachable students.”

But students chafed at the restrictions all the same. Sculptor Richard Deacon, one of the Locked Room’s participants, told ARTnews, “I thought the course was abusive and relied on the naive acceptance of the rules imposed by a group of young students with high aspirations and ambitions for the future. He described not having a clear understanding at the time what its point was and why students weren’t being encouraged for progress made. “I left St. Martins drained of energy and inspiration although my second year there, and was incredibly fruitful and productive of issues and concerns that continue to reverberate through my practice,” he said. Still, he remains broadly supportive of the experiment, citing the “extraordinary degree of solidarity” between the students, and the relationships he later built with some of the teaching staff.

Filmmaker Tony Hill said he similarly “found the rules overly authoritarian,” although he recalled mostly following them. Collective disgruntlement led to the course being bifurcated into A and B streams, where students were given a choice whether they wanted to shift to a more traditional model for their second year, an option Hill took. He found the first few weeks the most valuable, saying that “confronting a material and wondering what to do with it was an interesting creative challenge,” even as the rules seemed to be more of a conceit for the staff.

It’s unlikely that Locked Room had an impact on larger shifts in art education—but it is possible that, with critiques now taking place over Zoom and art classes being taught remotely, students could learn a lot from it right now. “I believe there is great benefit to having students be inventive and creative with form and content within tight limits,” Hill said, adding that his experience with the Locked Room has now informed his own teaching practice. “I do not see a benefit in regulating the social interactions of students. Often in art schools, they learn as much from each other as from the staff.”

[ad_2]

Source link