[ad_1]

On a recent summer evening, about 40 people sat in Freetown Hall in St. James Parish, Louisiana, passing around plastic objects: a water bottle, a pump moisturizer bottle and a tall food container.

Holding the food container in one hand, Beverley Alexander, a St. James Parish resident, approached Wilma Subra, an environmental scientist who drove in from Lafayette for the meeting.

“This is the plastic they are going to make at the plant?” she asked. Subra nodded yes. “Should I stop using these?” The scientist answered quietly, “That’s up to you.”

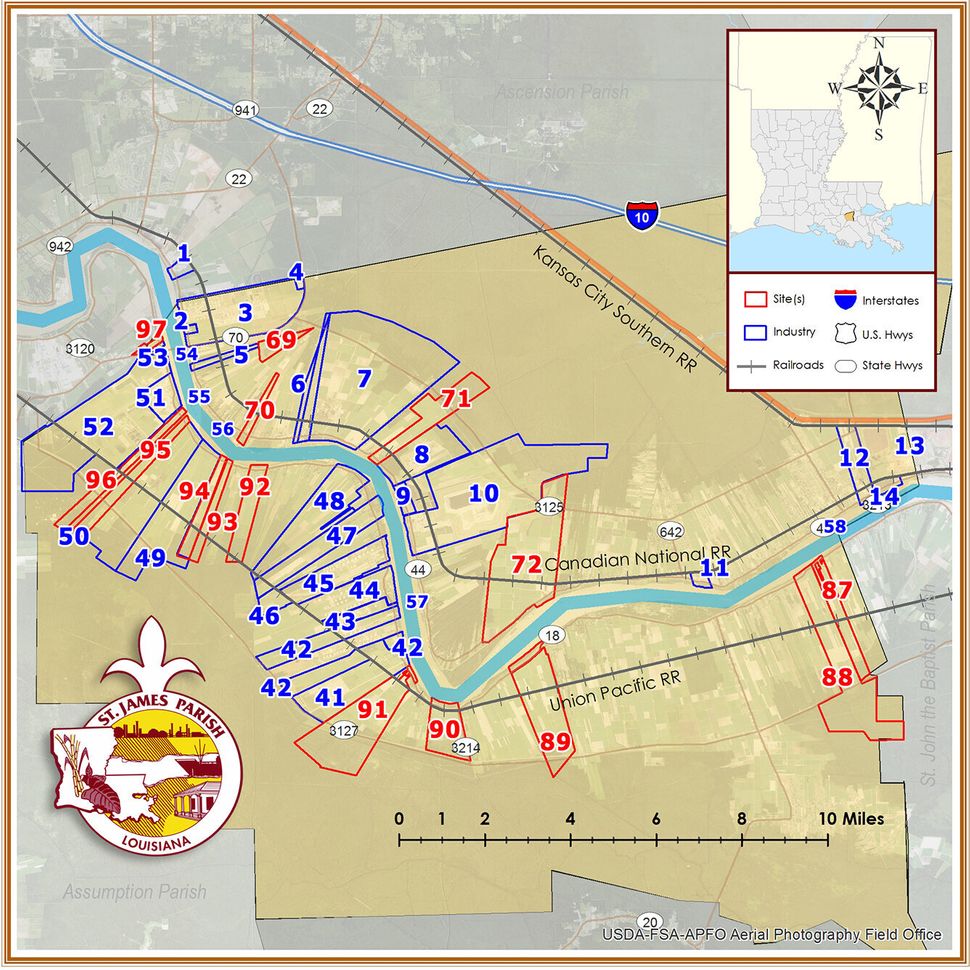

St. James is a rural community of just over 21,000 on the Mississippi River, better known for its plantations than its plastics. Some of its residents, as well as activists from around the state, had come to the hall to strategize how to stop the construction of a $9.4 billion chemical plant proposed by Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics. The facility, to cover 2,400 acres about 2 miles upriver from the meeting, would be the largest in the parish, which already hosts a fertilizer plant, a polystyrene plant and several oil and gas terminals and pipelines. It would also be one of the largest plastic producers in the nation.

The sprawling complex is set to comprise 10 separate plants that would use ethane, propane and natural gas to produce the base materials for the plastic bottles being passed around, as well as grocery bags, drainage pipes, clothing, astroturf and antifreeze.

In October, Sharon Lavigne, a lifelong resident of St. James and a school teacher, founded a nonprofit group called RISE St. James to fight the Formosa plant after hearing one too many times that it was “a done deal.”

“I didn’t buy that,” she told HuffPost. One day on her porch last year, Lavigne says she prayed on what to do and she got a clear answer: Rise and act. So she did. She organized residents to protest the plant, starting at the parish council hearings last year. RISE St. James works to get churches and other residents involved in the fight against the region’s chemical plants.

St. James lies in the middle of Louisiana’s petrochemical corridor, called “Cancer Alley” by many people in the state because of the emissions and pollutants released by the many industrial plants in the region.

Anyone you speak to here has had cancer or knows multiple people who have died from cancer. One resident told HuffPost she personally knows 70 people in the area who have died from cancer. Parents say their children have trouble breathing and suffer from skin rashes and nose bleeds. Last month, Lavigne and her group participated in a three-day march through Cancer Alley to talk with residents and local and state representatives about stopping construction of new plants in the state and asking for stronger regulations on existing plants.

The St. James residents gathered at the community hall live in the parish’s majority-African American Fifth District, where much of the gas and chemical industry is concentrated. They were determined to stop Formosa’s plans for their own health and the health of the planet.

“How many pollutants will they be putting into the water, the air and the land?” wondered Milton Cayette Jr., Lavigne’s brother and a member of RISE St. James who used to work at a chemical plant in the parish.

That’s exactly what Subra, who won a MacArthur Fellowship “Genius” Award for helping citizens like those in St. James, was there to talk about.

According to the 15 state air permits Formosa has applied for, she explained, the plant would become the state’s largest emitter of ethylene oxide and the second largest emitter of benzene – both known carcinogens. Other emissions would include formaldehyde, large amounts of particulate matter, sulfuric acid and toluene, chemicals that are dangerous and can cause cancer, Subra said. The plant will release more than 13 million tons of a carbon-dioxide equivalent a year, according to the air permit — as much as a large coal-fired power plant.

If the facility opens as planned, Subra said, “I’ll be here doing health surveys all the time.”

St. James lies in the middle of Louisiana’s petrochemical corridor, commonly called “Cancer Alley.”

In January, the plant received final approval from St. James Parish council and received a coastal use permit from Louisiana.

Fifth District councilman Clyde Cooper, who represents the area where the plant will be built, said he voted for the plant because it met all of the parish’s land use requirements. He also supports it because Formosa agreed to do everything the council asked of it, such as providing job training and hiring preferences for local workers. But he told HuffPost that he doesn’t personally support the plant, explaining that he agrees with the environmental justice claims made by opponents, pointing out that these issues affect citizens in other parts of the state as well. “It’s not just a [Formosa] plant problem, it’s a problem with the political arena,” he said.

The state will hold a public hearing on the remaining air permits on July 9; it will be one of the last chances the community will have to stop the plant. Public comment on the permits ends Aug. 12. Greg Langley, a spokesman for the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, the agency responsible for issuing air permits, said the permit process is the time when the agency will consider the citizens’ concerns.

St. James residents know the plant is being built because of the demand for plastics that is being driven by cheap natural gas from the fracking boom. The American Chemistry Council counts 334 newly announced or in-construction chemical plants in the United States (including those producing plastics, fertilizers and more), totaling more than $200 billion in investments from around the world.

The growing attention to plastic waste has helped RISE St. James attract state and national support in its resistance effort. The Center for Biological Diversity and Sierra Club are among the groups helping out with professional expertise, as is Break Free from Plastic, a worldwide nonprofit that is tracking other plastic plant announcements around the United States and globally and is working with local groups in those places to stop their construction.

“We were looking around the country and realizing there are Formosa-like facilities popping up all over the place, in Appalachia and the Gulf Coast in particular,” said Julie Teel Simmonds, a senior attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity.

The story of St. James stood out.

Lavigne, who was born in St. James during the Jim Crow era, said she and other African American residents were not informed when, in 2014, the northern part of the Fifth District was rezoned for industrial use.

“While white residents sold their properties and moved away, black residents did not receive buy-out offers,” she wrote in an essay published in February. “We were left inhaling the toxic air produced by the invading petrochemical plants.”

Those who were left saw their homes — many of which had been handed down for generations — lose value. “My house may be worth a million bucks to me, but it’s not worth anything to anyone else,” said Barbara Washington, who lives surrounded by industry on the east bank of the Mississippi River. Some have been forced to leave their family homes to go where the air is cleaner.

With the rezoning, and after years of higher-income white residents moving away, a post office, a school and businesses closed up.

The situation in St. James “really shook us,” said Simmonds. “They’ve already had such an industrial presence and they really seem to be getting pushed out of their homes, and basically losing all of the services.”

Formosa, which didn’t return calls seeking comment, details that there are 154 people living within a 1-mile radius of the plant and 81% of them are part of a minority group, according to information that Subra supplied from the air permits at the meeting. Two miles around the plant, the population is 1,660 with a minority population of 87%, she added, and within a 5-mile radius, there are 7,021 people with a minority population of 74%.

“Even though an African-American community is located in the general vicinity, this fact alone does not constitute environmental racism,” the company wrote in its permit application.

The true picture of the problem is often obscured because many of the parish’s residents work for the chemical companies or know people who do, so they are often reluctant to speak up.

But Washington urges people to use their voices. “This fight is bigger than us,” she said. “It’s a fight to liberate us from the oppression from industry.”

Other fights against chemical plants in the state have failed. But Jane Patton, a Louisiana native who is a leader with No Waste Louisiana and a member of Break Free from Plastic, says she believes the fight against Formosa will be successful.

“In the past when we were fighting Shintech [a producer of PVC] or even the last time we fought Formosa here, we were fighting a single plant. But we were fighting them one at a time,” said Patton, referring to a Formosa plant that was built in Baton Rouge.

Now, she said, more people are paying attention to the entire lifecycle of plastic waste and pollution — from production to disposal. Organized at local, national and international levels, groups are beginning to attack the construction of new plants on multiple fronts.

Patton, like so many of her neighbors growing up, never thought about the purpose of the massive petrochemical plants belching out toxic fumes and polluting the water. The 32-year-old activist told HuffPost she herself only realized when she was 25 that the state’s ubiquitous petrochemical plants were making plastics. With the increasing toll of plastics production now part of the popular conversation, local residents and conservationists from other parts of the country are more aware than ever of how Cancer Alley’s health crisis fits into a global tale of industrial excess and environmental justice.

When she was younger, Patton said, “there was less concern about the actual product they would be making. Now we know they are part of a plastic production supply chain, and we are collectively saying: We don’t need that.”

Global demand for plastics outpaces other bulk materials, including cement and steel, according to the International Energy Agency. By 2030, plastics and other petrochemicals will account for more than a third of the growth in world oil demand and nearly half of it by 2050.

Even if Alexander does stop using those plastic food containers, or even if the entire state of Louisiana stopped using plastic, Patton believes it wouldn’t make a dent in the growing worldwide production of plastics.

“Just the demand side is not going to fix the problem. It just won’t,” she said, explaining that things like straw bans or plastic bag bans are great, but not enough. In order to make a difference, she said, new plastics plants like Formosa’s will have to be stopped.

This fight is bigger than us. It’s a fight to liberate us from the oppression from industry.

St. James resident Barbara Washington

In Texas, where Formosa has a plant in Point Comfort, the company has been called a “serial offender” and “worst polluter” for dumping the tiny plastic pellets it creates into Gulf waterways and spewing dangerous concentrations of emissions into the air. A June 29 federal court ruling against the plant in Texas has given those in St. James hope.

Lavigne is determined not to let history repeat itself in St. James. “We’re already suffering from too much industrial pollution, my kids and grandkids are suffering, and now they want to put more on us. We can’t let that happen,” she said in a press statement released with the Center for Biological Diversity in June.

If getting on the anti-plastics bandwagon and marching through Cancer Alley with a reusable water bottle will help, she is willing to try.

“Maybe we don’t need plastics,” she said. “Let’s do whatever it takes.”

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to [email protected].

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link