[ad_1]

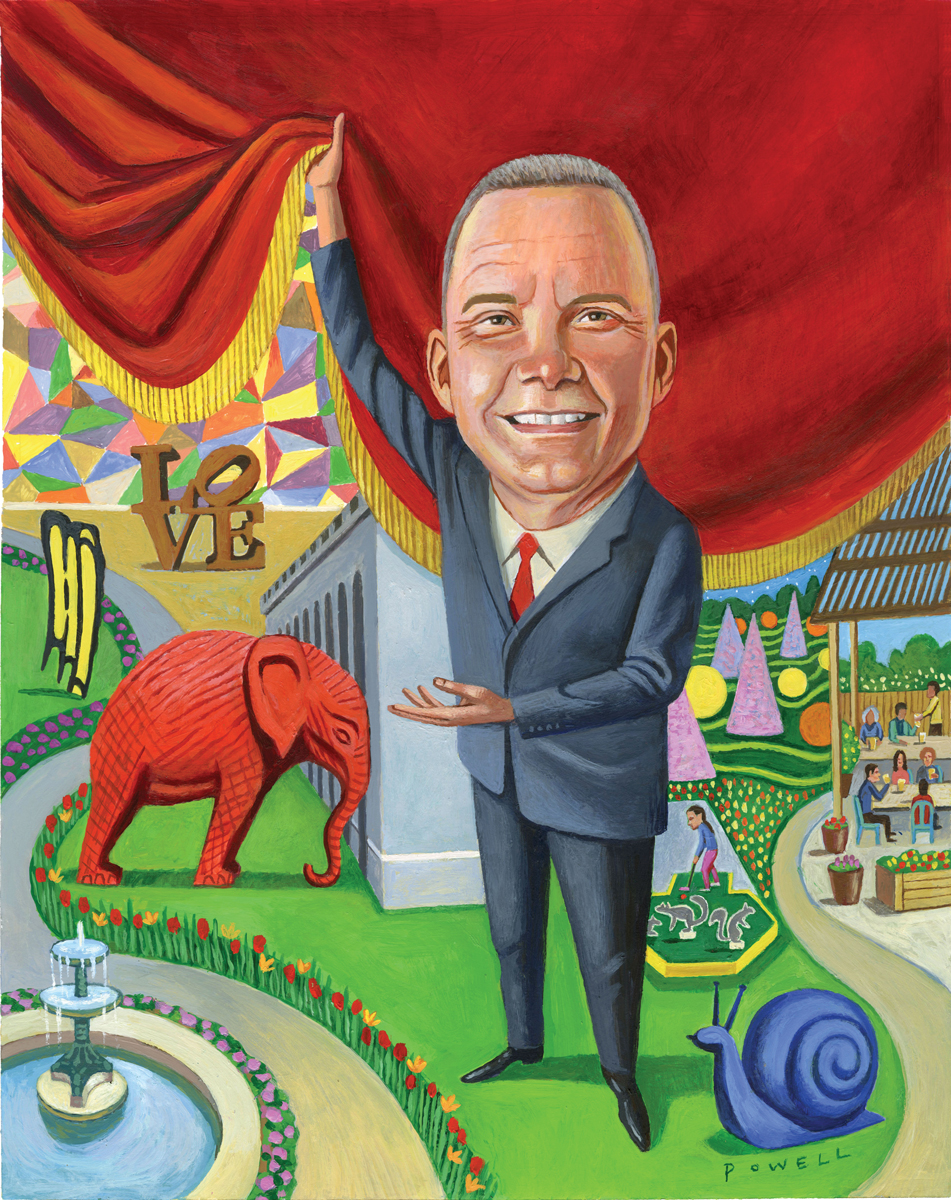

Charles Venable presents the sprawling Newfields grounds in Indianapolis.

CHARLIE POWELL

The pop-up Japanese-style teahouse at Newfields, the institution formerly known as the Indianapolis Museum of Art, is positioned at the top of a long escalator in the museum’s soaring glass-fronted entrance pavilion. If you look into the next room, you can see one of the city’s crown jewels, Robert Indiana’s original 1970 Love sculpture. In April, I was seated in the teahouse with Charles L. Venable, Newfields’s director of seven years, who wanted me to meet the museum’s first-ever culinary director, Josh Ratliff, one of only nine certified sommeliers in the Hoosier State. Ratliff ordered us pots of blooming tea, and presented me with a “magic apple” that had been marinated in dry tea. Venable, who at 59 retains a touch of a Texas twang from his childhood in Houston, announced that “art is not better than apples.” He winked—“There’s a quote,” he said with a grin—and voiced what his critics might say about such a proclamation: “He truly is the devil.”

Venable expounded excitedly about the fruit in front of us. “Organic produce has a history, and a connoisseur can talk about the 10,000-year history of apples,” he said, mentioning the orchard on the museum grounds. Then he told me about the teahouse’s future. “This turns into a ramen shop next,” he said, gesturing around the space. “If we had a Russian show, you could be doing vodka tastings.”

The teahouse, Venable explained—as we walked in the pavilion beneath kinetic sculptures by Studio Drift that evoke huge flowers—is tied to exhibitions of Japanese fashion and art. “I think we’re probably the first art museum that has decided food is also an art form,” he said. “So is wine, sake, tea. So we have a director of culinary arts.”

The multipurpose café space is just one of many unorthodox ideas that Venable has tried out at the art museum he rechristened, in 2017, as Newfields, A Place for Nature & the Arts. There has also been the crowd-pleasing holiday festival called Winterlights, a mini golf course, and a pumpkin show this fall in conjunction with a Yayoi Kusama exhibition. These experiments have made him a controversial figure, locally and beyond.

[See the Table of Contents for the Summer 2019 edition of ARTnews: “Reshaping the American Museum.”]

Critics have accused Venable of dumbing down the museum with his crowd-pleasing, cost-conscious changes. But his program has also touched a nerve as institutions around the country confront a tough new calculus. Young philanthropists are eyeing returns on their giving, and corporate funding isn’t what it used to be. The National Endowment for the Arts’ budget has been flat for a decade. Skyrocketing prices have made it difficult for museums to acquire art, particularly contemporary art, and they are having to think about new ways to compete for audiences, especially in cities where tourism is low.

In the teahouse, Venable brought up the beer garden he’d opened on the museum’s grounds, and—once again pretending to be one of his detractors—said, “You care more about beer than you care about Matisse! And by the way, I’ve never been to Indiana.”

“And guess what,” Ratliff, the sommelier, cut in. “Hoosiers do care more about beer than Matisse.”

“That’s true,” Venable said. “I would say more Americans care about beer. Our studies will tell you.”

Citing objects in the museum’s collection that speak to beer history, Venable said he has been asking himself how he can “connect those dots” between artworks and experiences, food and scholarship. “We’re going to work on that. Because more people like beer—and I’m not giving up on all those people out there.”

Along with a renowned collection of Japanese painting and one of America’s finest Post-Impressionist collections, Newfields is home to Rembrandt’s first self-portrait, an extended loan expected to become a gift in 2021. “If you want to see our Rembrandt, we would love for you to do that,” Venable said. But if you would prefer instead to have tea, or wander the grounds, or enjoy the one million lights of Winterlights, or have a craft beer with friends, well, Newfields can be a destination for that too. He insisted that his job—along with maintaining responsible stewardship and dealing with tough financial realities—includes welcoming a larger audience. “It’s about saying: We’re not going to judge you, Mr. Member of the Public.”

An aerial view of Newfields, with 100 Acres, at top, and the Lilly House and gardens, at right.

COURTESY NEWFIELDS

Like other large encyclopedic museums in the United States—the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York—the Indianapolis Museum of Art had roots in the 19th-century premise that art was meant to edify and enlighten. The institution, in essence, was a gift from the elite to the masses. In 1883, May Wright Sewall, the principal of a girls’ school, joined with other citizens to start the Art Association of Indianapolis, which offered classes and exhibitions. It was a modest organization, but it got a shot in the arm in 1895, when a real estate baron named John Herron bequeathed it $225,000 to create the John Herron Art Institute. In 1966, two great-grandchildren of local pharmaceutical entrepreneur Eli Lilly offered their parents’ Oldfields estate to the institution, farther from the town center, to expand. Museum leadership rechristened the organization the Indianapolis Museum of Art and made the move, opening there in 1970.

Other big gifts followed. In 1989, Dorothy Lynn, the widow of an Eli Lilly executive, made an anonymous gift of $29 million, bringing the IMA’s endowment to $100 million, and in 1996, Enid Goodrich, the widow of Pierre Goodrich, a businessman who backed the Indianapolis Star, bequeathed it $40 million. By then, the institution’s total properties consisted of the museum building, 40 acres of gardens around the Lilly estate, and about 100 acres of parkland. Today, the building measures 670,000 square feet, with 179,000 square feet of exhibition space, a size it reached after an expansion in 2005.

When Venable’s predecessor, Maxwell Anderson, arrived at IMA in 2006, after a five-year stint (1998–2003) at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, he began his directorship with an endowment of more than $360 million. He pursued high-profile, high-cost projects, like a huge sculpture park called 100 Acres in the parkland, stocked with works by Alfredo Jaar, Andrea Zittel, and Atelier Van Lieshout; a conservation-science department; and exhibitions such as “Power and Glory: Court Arts of China’s Ming Dynasty” and “Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial.” All the while, the endowment grew. By 2008, it stood at $393 million, ranking it in the top 15 endowments for U.S. art museums.

That endowment has been crucial for the IMA, which has regularly received upwards of 60 percent of its annual revenue from investments. That figure is high but not out of step with some other large art museums, like the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, which receive more than 50 percent from such funds. A renewable resource of money is especially important for institutions when other means of support are lax or inconsistent, as is the case with government funding in Indiana. In the 2017–18 fiscal year, Newfields received just $366,000—less than 2 percent of its budget—from government grants. (On average, U.S. museums receive 15 percent of their revenue from such sources, according to the Association of Art Museum Directors.)

“Museums love to have endowment money because they don’t have to raise it from difficult donors,” said David Gordon, a museum consultant. It also allows them to resist the pressure to sell tickets to make ends meet. The downside is that, when the economy takes a hit, such institutions feel the pinch—which is what happened in 2008. Nationwide, the most visible casualty of the collapse was the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, which nearly depleted its endowment through deficit spending. The IMA was also hit hard: it lost more than $100 million. The museum responded by cutting its budget, laying off staffers, and replacing dozens of security guards with college students in an effort to reduce the draw on its diminished endowment.

Rembrandt van Rijn’s Self-Portrait, ca. 1629, is on long-term loan to Newfields.

INDIANAPOLIS MUSEUM OF ART AT NEWFIELDS, COURTESY OF THE CLOWES FUND

Venable has preached fiscal conservatism from the start of his directorship in 2012. Just months before his appointment, the Moody’s credit-rating agency revised its outlook for the IMA from stable to negative, citing its debt burden and heavy reliance on investment income. Not long after arriving, the new director cut two dozen people from a staff reeling from the more extensive layoffs in the wake of the recession. He has also pursued a mission to pay off the museum’s debt, owing to its expansion in 2005, by 2026.

What struck Venable—when he arrived in Indianapolis from the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, where he was director from 2007 to 2012—was the discrepancy between the monumental size of the museum and the modest size of the city it serves, which has about 880,000 residents. “This community has built an institution of a scale that should be in New York or Los Angeles or maybe Chicago,” he told me. “We’re scaled for a million visitors a year, so how do you make sense of that?”

One way to make sense of it is to try to draw crowds, as Venable did, first in a traditional museum-director fashion, with blockbuster exhibitions. In 2013, “Matisse, Life in Color: Masterworks from the Baltimore Museum of Art” brought in about 50,000 visitors over its three-month run. In 2015, “Dream Cars,” a show co-organized with Atlanta’s High Museum of Art that included a 1935 Bugatti and a 1955 Chrysler-Ghia Gilda, brought in 63,000. These were some of the highest attendance numbers the IMA had ever drawn, but from the perspective of Venable and his team, they were not satisfactory because, on a per-person basis, they were too costly. As Preston Bautista, Newfields’s deputy director for public programs and audience engagement, put it to me over lunch in the museum’s cafeteria, “I can’t justify a million-dollar show when I can’t recoup the income.”

The next step in Venable’s belt-tightening measures, in 2015, was to do away with free admission. The museum had been free since 2007, when Anderson dropped a $7 charge instituted in 2005. Venable, by contrast instituted a charge for adults of $18. He also gated off the 40-acre garden adjacent to the museum that had been open to the public without charge, and made access to it contingent on paying the museum’s entrance fee.

Per-person costs aren’t the only thing on Venable’s radar. Venable has also looked at the expense of maintaining the collection. He and his team have taken up the cause of assigning letter grades to the institution’s more than 50,000 objects—A through D—with an eye toward managing conservation costs. Georgia O’Keeffe’s majestic Jimson Weed (1936) got an A; Merio Ameglio’s Le Pont Neuf (ca. 1940), a D.

Venable’s laser focus on expenses was paired with the decision to pay down debt. When he joined the museum, some $123 million in bonds from the 2005 expansion remained on the museum’s books. So far, more than $40 million has been paid off, which has involved allocating endowment funds. According to Venable, it just isn’t sexy for donors to fund paying off a museum’s debt. “Talk about money that nobody wants to give you,” he said. “That’s $40 million of exhibitions I could have done, $40 million of curators I could have hired, $40 million worth of fill-in-the-blank.”

Opinions vary dramatically on how museums should handle debt. “It’s quite subjective,” said Gordon, the museum consultant, who said he prioritized retiring debt when he led the Milwaukee Art Museum in the 2000s. “I think it’s a prudential position to take, to pay off your debt. It’s one of the things that guarantees your independence. You’re never going to be at the mercy of banks or creditors.”

But another line of reasoning is that, with interest rates low and markets performing well, it is a fine time to have bonds on the balance sheet.

Venable has defended his choice. “Debt is debt,” he said, arguing that, in the event of another 2008 crash, the bank could suddenly demand payment on nearly $80 million in loaned money, endangering the museum.

To bolster the museum’s financial position, he has pursued steady streams of revenue—$1 million from admission charges and $1 million from memberships toward a $29 million budget—by favoring recurring festivals over a parade of costly one-off art shows.

And hence was born the bête noire of his critics: Winterlights.

View of the Winterlights festival in front of the Lilly House.

COURTESY NEWFIELDS

To what extent museums should be places of entertainment has been a subject of heated debate for decades. Should they lean toward serving the public in large numbers, or double down on their commitment to being specialized places dedicated to the highest scholarship and conservation? Every once in a while, a new vision comes along and reignites that debate. In 2017, when Venable changed the name of the institution from the IMA to Newfields, he also launched the Winterlights festival. Arriving after sundown when the galleries were closed, visitors paid $25 to goggle at a million twinkling lights strung around the grounds while Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker Suite” emitted from strategically placed speakers.

The idea didn’t come out of nowhere. Devoted museumgoers love moving quietly through exhibitions, pausing to read wall labels, but “in some ways that is not normal,” Venable said. He read studies from the marketing firm LaPlaca Cohen that showed that people want to eat, be outdoors, and do things when consuming culture. And he realized that with 40 acres of gardens, he was sitting on facilities to offer all of that. According to research he commissioned, there were hundreds of thousands of locals who had never visited the museum but might respond to a new pitch.

From an attendance perspective, Winterlights was a runaway success. Its 69,000 visitors in 2017 nearly doubled the 35,000-person goal the museum had set, and it drew 110,000 in 2018. About 20 percent of those visitors had never been to the campus before. From a perception perspective, the spectacle has met with mixed reviews. A former Newfields employee, who agreed to comment on condition of anonymity, said of Venable, “He sees his million lights as art. I see it as a shallow sham of an experience to get people in the door.”

Winterlights is the largest and most visible of Newfields experiments in visitor experiences, but it is far from the only one. In 2014, Venable brought on Scott Stulen as curator of audience experiences and performance. (Stulen has since gone on to lead a museum himself, as the director of the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma.) Stulen came to the IMA from the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, where he ran a cat-video festival and an artist-designed miniature golf course, both of which he imported to Indianapolis. Stulen realized that museums were competing with many more things for people’s leisure time, and he decided to go head-to-head with them. “Even going back 15 years, there was no Netflix,” he told me. “There were no smartphones. Now there’s all this competition for time, attention, and money, and you need to change the game to get that audience that’s not your core audience.”

“Museums for a long time have been in this kind of cycle,” Stulen continued. “You do this blockbuster show, your membership spikes, but you lose money on it, almost always, and membership dips down again,” Stulen said.

That is not a sustainable strategy, according to Venable. “That experiment has run its course,” he said. “We can predict with amazing accuracy how many people will come to a show here.” By which—compared to Winterlights—he means how few. At the pop-up teahouse, Venable wondered if it was “ethical and fair” to spend large amounts of money on shows that attract only small, specialized audiences. “As these great repositories of human creativity,” he said, “are we going to be relevant to enough people to warrant social and financial investment 50 years from now?”

Venable has been careful to position Winterlights as a botanical-garden offering, rather than a substitution for art exhibitions, but it clearly has a grip on the institution. “My goal, really, is to beat Winterlights,” Bautista, the deputy director, said. “But how I do that with art is the question. Clearly, Winterlights is relevant to the community. They’re willing to pay $25 for this thing. How do I do that with this incredible collection that we have? I don’t know the answer to that yet but that’s what we’re mapping out right now.”

Criticism of this focus has dogged Venable’s tenure from its start. “I feel very comfortable saying that my vision doesn’t align with Venable’s” the contemporary art curator Sarah Urist Green told the local publication Nuvo in 2013 on her way out the door. And there are those in Indianapolis who pine for the days of loan-intensive shows like “Roman Art from the Louvre” and “Sacred Spain.” “I hear a lot of people say that it’s been many years since we’ve had an interesting show,” said Jeremy Efroymson, whose family name is on the museum’s entrance pavilion as a result of a 2002 gift. He added, of the museum’s transformation into Newfields, that for some, “when you rename it, and you take the name of the city and the name of the museum out, that just feels wrong.”

Venable insisted that ambitious, large-scale exhibitions are not a vestige of the past. “What is fair to say is that we are being exceedingly disciplined about when we program those shows,” he said.

Spring blooms on the grounds of Newfields.

COURTESY NEWFIELDS

After the IMA was officially rechristened as Newfields, A Place for Nature and the Arts, in August 2017, the Washington, D.C.-based critic Kriston Capps fired off a column in CityLabs saying that “Venable has turned a grand encyclopedic museum into a cheap Midwestern boardwalk,” and calling Newfields the “greatest travesty in the art world in 2017.”

In a recent op-ed in Nuvo, Bill Watts, an English professor at nearby Butler University, termed Newfields a “nowhere name” and accused it of becoming “less a museum and more like an 18th-century pleasure garden.” Watts told me, “One of the painful things to me is that this is a marketing campaign that is driving an institution that should be driven by ideas, and by some sense of civic responsibility.”

Others in Indianapolis said they had concerns but declined to speak. “It’s hard for people to talk about it because then you’re drawing lines,” Efroymson explained. “And it’s a small art community.” Located in the 34th largest metropolitan area in the country, Indianapolis has a compact art scene, with a limited number of commercial galleries and nonprofit organizations. Michael Kaufmann, who leads the the nomadic Indianapolis Contemporary (formerly the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art), pointed out that this has given Newfields an outsize role to play. “There’s pressure for them to be all things to all people,” he said. “Inevitably, depending on how you pivot organizationally, people are going to be upset.”

Newfields has its defenders. “Enjoy your art snobbery,” one letter writer retorted to critics in the Indianapolis Star. “We in Indianapolis don’t need your approval to know we have a fantastic art museum and beautiful Newfields campus to enjoy.”

“Museum is a dirty word,” said Matt Gutwein, who joined the IMA board in 2010 and remains a Newfields board member, explaining that it alienates many. He said that, in plotting the Newfields agenda, Venable and the board looked at everything they had—the museum’s collection, the gardens, the sprawling 100 Acres art park, historic homes—and thought, “How can we take full advantage of those assets to give really enriching experiences to those who visit?”

But populism works only if people show up, and the overall attendance picture at Newfields is opaque.

Under Anderson, when general admission was free, the IMA reported an annual average of about 400,000 visitors to the building—a number it generated using heat-tracking sensors employed by many museums. It did not count visitors to the overall grounds, which people could stroll without setting foot in the museum. A museum staffer told attendees at the Museum Next conference in 2016 that, after the $18 admission was instituted, visitors dropped and “our population became older, whiter, richer, and less families.” However, even as ticket sales showed a lower number than past counts, the sensors showed an increase, so “we are hard-pressed to say that there was a decrease in attendance as a result of the change in policy,” a spokesperson told me. (The sensors were subsequently removed.)

For the 2017–18 fiscal year, Newfields reported about 399,900 visitors, but that included everyone visiting the grounds (both the free 100 Acres and the gated gardens). Of those, 188,000 were general admission visitors, meaning they bought a ticket or had a membership. (The rest went to the no-charge 100 Acres, came with a school group, or visited through other special programming.)

With Winterlights bringing in some 69,000 people over the course of about two months, that makes the tally for general-admission visitors to the museum for the entire year only about 119,000. (The building itself is closed in the evening during the festival.)

Newfields has said that Anderson’s sensors were likely overcounting, and the spokesperson called them “unreliable and not a true comparison to our actual numbers after we started charging admission.” Anderson and the sensor company have gone on the record defending the accuracy of their count, a debate detailed in the Indianapolis Monthly.

In any case, by the institution’s own accounting, attendance is growing—the total in 2015–16 being 315,900. The goal is to have 500,000 visitors by 2026, with 350,000 paying general admission.

In other goals set by museum leadership, Newfields is trending in the right direction. The endowment draw required to operate the museum is down, as projects like Winterlights increase revenue, and the board is planning a capital campaign. And the debt is being paid off, albeit at the cost of endowment growth. While the museum has received grants for infrastructure projects, it has had difficulty bringing in gifts for its endowment, so as market returns have gone to pay off debt, it has hovered in the mid-$300 millions, where it was more than a decade ago.

In 2016, amid all of the ongoing changes, the board gave Venable a 10-year contract extension, quite lengthy by museum standards. “I am really grateful that we have Charles at our institution,” Gutwein said. “I think he is an extraordinary leader and visionary, and . . . the results that he and his staff and the board have achieved speak for themselves.”

A museum tour group viewing works by Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh.

COURTESY NEWFIELDS

Asked about the changes in Indianapolis, Maxwell Anderson was diplomatic. “I think it’s the right of any board to determine the course of the institution that it governs,” he said. “I continue to believe that art museums should, at their root, be based on scholarship, research, and education, and would hope that the Indianapolis Museum of Art invests in those robustly.”

Venable argues he is doing just that. One recent hire is Kelli Morgan, who came over from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia to be associate curator of American art. She’s working on a rehang of the American galleries aimed at decentering the United States and including Latin American and indigenous objects, and she recently co-curated an exhibition by local artist Samuel Levi Jones with paintings that address oppression and injustice.

Venable pointed to that show and another recent exhibition, of erotic photographs by George Platt Lynes, as evidence of his seriousness about presenting important art. “I do wish some of the folks who have been so fixated on how we decorate our trees during the holidays would actually care about how we’re pushing the envelope in the state of Indiana through art,” he said. Community members hailed Venable, who married his husband, Martin K. Webb, in 2013, for speaking out against the anti-gay religious freedom legislation signed by then Indiana Governor Mike Pence in 2015. And for those wanting a blockbuster, a show of work by Edward Hopper—Newfields owns two great paintings by him—is on tap for 2020, co-organized with the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond.

Viewer feedback is central to the Venable model. Showing me through the museum’s 11,000-square-foot modern and contemporary design gallery (the largest in the country), another Venable hire, associate curator of design and decorative arts Shelley Selim, told me she cut 100 objects—about 20 percent of the pieces—in her recent rehang, in response to a survey in which visitors said they felt there were too many works on view.

Curators at Newfields “definitely don’t have as much power as other places where I’ve worked,” said Selim, a veteran of the Museum of Arts and Design in New York and the Cranbrook Art Museum in Michigan. Referring to the team shaping the museum, she said, “The more cooks you get in a kitchen, the more collaborative it is, and the more you’re going to create a product that appeals to a broader range of people.”

Many times during my visit to Newfields, I made my way outdoors, walking past the old Lilly mansion, along manicured allées and blooming flowers that Venable has argued the museum never properly marketed.

Newfields’s horticulture director, Jonathan Wright, hired away from the Chanticleer Gardens in Pennsylvania, showed me around. “From a gardener’s perspective, they didn’t get the prominence they deserved,” he said of the greenery. “But I fully get it—you were building an incredible art museum.” He described how he wants to “double down on the romance of the orchard” and possibly bring in the fountain consultant who worked on the Bellagio hotel and casino in Las Vegas to assist in restoring one of the fountains on the grounds.

Wright also described the upcoming autumn festival, Harvest, slated to coincide with the Yayoi Kusama show. Kusama, one of the most renowned artists of the postwar period, is known for, among other things, large sculptures in the shape of pumpkins. The festival, he said, “will be celebrating everything that’s fantastic about being in the Midwest, in Indiana, in the fall. What’s a better theme than pumpkins for the fall? There will be pumpkins inside and out, including an incredible Kusama exhibition in the galleries. Outside, we’ve got tons of pumpkins coming in from all over the state.” The overall effect, he said, will be of “infinite pumpkins.”

As sunset neared, I roamed the museum’s galleries and found them almost empty. But it was shaping up to be a beautiful evening, and over in the 100 Acres park, a few young girls were jumping between the bones of a giant skeleton sculpture by Atelier van Lieshout and a couple was sharing an intimate moment on its head. In the beer garden, outside an orchid-filled greenhouse, people were enjoying a hoppy exclusive-to-Newfields craft brew, giant pretzels, and zesty cheese spread. I sat down and bit into the tea-soaked apple that Ratliff had given me. It was delicious.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of ARTnews on page 60 under the title “Come One,

Come All!.”

[ad_2]

Source link