[ad_1]

“Picturing Herstory” panelists, from left, Joan E. Biren (JEB), Lola Flash, and Tiona Nekkia McClodden.

©JADE GREENE

In June, as part of Pride Month, ARTnews hosted a panel titled “Picturing Herstory: Queer Artists on Lesbian Visibility,” in partnership with the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, at Spring Place in New York. For the panel, ARTnews convened artists Joan E. Biren (JEB), Lola Flash, and Tiona Nekkia McClodden to discuss how they began making art, why it’s important to center people who have historically been excluded from the mainstream, and the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising.

McClodden is a Philadelphia-based visual artist, filmmaker, and curator whose work explores intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and social commentary. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2019, and her work is currently on view in the 2019 Whitney Biennial in New York.

Flash uses photography to challenge gender, sexual, and racial norms and stereotypes. Her work is in the collections of Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Brooklyn Museum. In 2018, she had a career retrospective at Pen + Brush in New York, and her work is currently on view in a solo show at Autograph in London, and in the “Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989” exhibition at the Leslie-Lohman and the Grey Art Gallery.

JEB is an internationally recognized documentarian, artist, and activist who began chronicling the lives of feminists, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in 1971. She is the author of two groundbreaking volumes of lesbian photography and her slideshow, Lesbian Images and Photography, 1850 to the Present, also known as the “Dyke Show,” is considered a seminal work within the history of queer art. She was commissioned to create the Leslie-Lohman’s 2019 “QUEERPOWER” window work, and her art is in six major exhibitions timed to the 50th anniversary of Stonewall.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

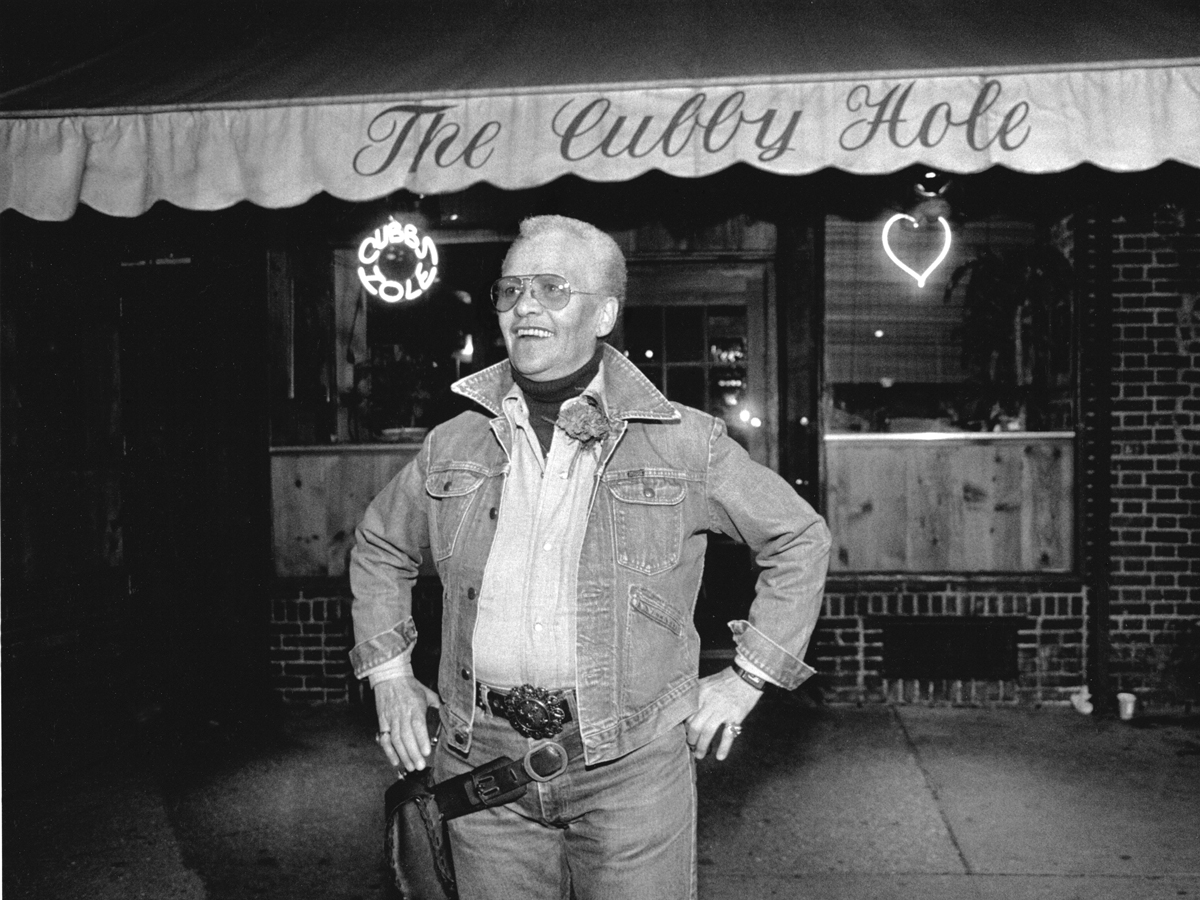

Joan E. Biren (JEB), Stormè DeLarverie working as a bouncer at The Cubby Hole Bar, NYC, 1986.

©2019 JEB (JOAN E. BIREN)/COURTESY THE ARTIST

ARTnews: How did you get into art-making? Was visibility for your various communities part of your practice from the beginning?

Tiona Nekkia McClodden: I have to start with my first film, when I thought I wanted to be a formal documentary filmmaker. It’s really poignant because I was talking to Joan earlier about Michelle Parkerson who did the film Storme: Lady of the Jewel Box, about [activist] Stormé DeLarverie. Michelle is in my first film, Black./Womyn.: Conversations with Lesbians of African Descent. It was finished in 2008 and released on DVD in 2010. It took me six years to make that film. It really was about getting out and trying to disrupt the monolith of what a black lesbian could be at the time: flush out the definition, give a certain kind of visual to it, and interrogate the community itself, around how its members wanted to be identified in relation to how I wanted to be identified. I felt constantly policed or shrunken down, in the ways that I had in interactions with several elders in the South when I was growing up. I think some of the questions that I was asking are being revealed right now as I’ve gotten older.

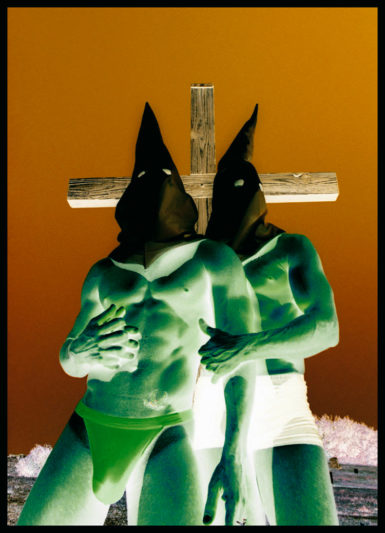

Lola Flash, K is for KKK, ca. 1993.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Lola Flash: For me, I started off when I was a kid with a camera. It was like my friend. I was an only child, so I just took pictures. But when I got to Maryland Institute College of Art, I started doing this cross-color stuff, which was basically printing a slide onto the wrong kind of paper to reverse the colors. Since I was in an academic environment, my teachers were like, “What is she doing?” So, I had to figure out what was I doing. I realized that, in my pictures, black was white, and white was black. As a kid, I remember I read in the dictionary that “black” was bad and awful and dirty, and that “white” was pure and angelic.

I’m sure it stuck in my head, because in my pictures I was turning everything around. I took a picture of Martina Navratilova serving at the U.S. Open, and all the people in the background look like they are black. So, I made my world black. It wasn’t until then that I realized that I could actually say something with my work, that we, as artists, are supposed to show everyone how we see the world. I went on to take pictures of people who look like me or my friends—people who I didn’t see represented in the museums and galleries. My mission is pretty much to put brown faces on white walls.

JEB: In 1970, I was in radical lesbian feminist separatist collective called the Furies, and we thought we were very revolutionary. All of our patriarchal learning was polluted. We actually called it [having] “a prick in the head,” so if you talked and wrote like somebody who… you get the idea. You had to do something else. I had a very privileged education, but it was not an art education. So, the something else had to be art, but I couldn’t draw. That’s how I became a photographer in the early ’70s. I wanted to see pictures of lesbians, and all the pictures of lesbians that I saw were the young, slim, white, blonde, wispy [ones]—what I call, “faux lesbians” made for the male gaze, these sort of pornographic monster lesbians. They didn’t look anything like me or my friends. I decided that, if I wanted to see those images, I would have to make them myself. I taught myself photography, and I started to find lesbians who were willing to come in front of my camera, which was not easy in the beginning, because I told everyone, “This is for publication.” The reason I was making the images was so other people would be able to see them.

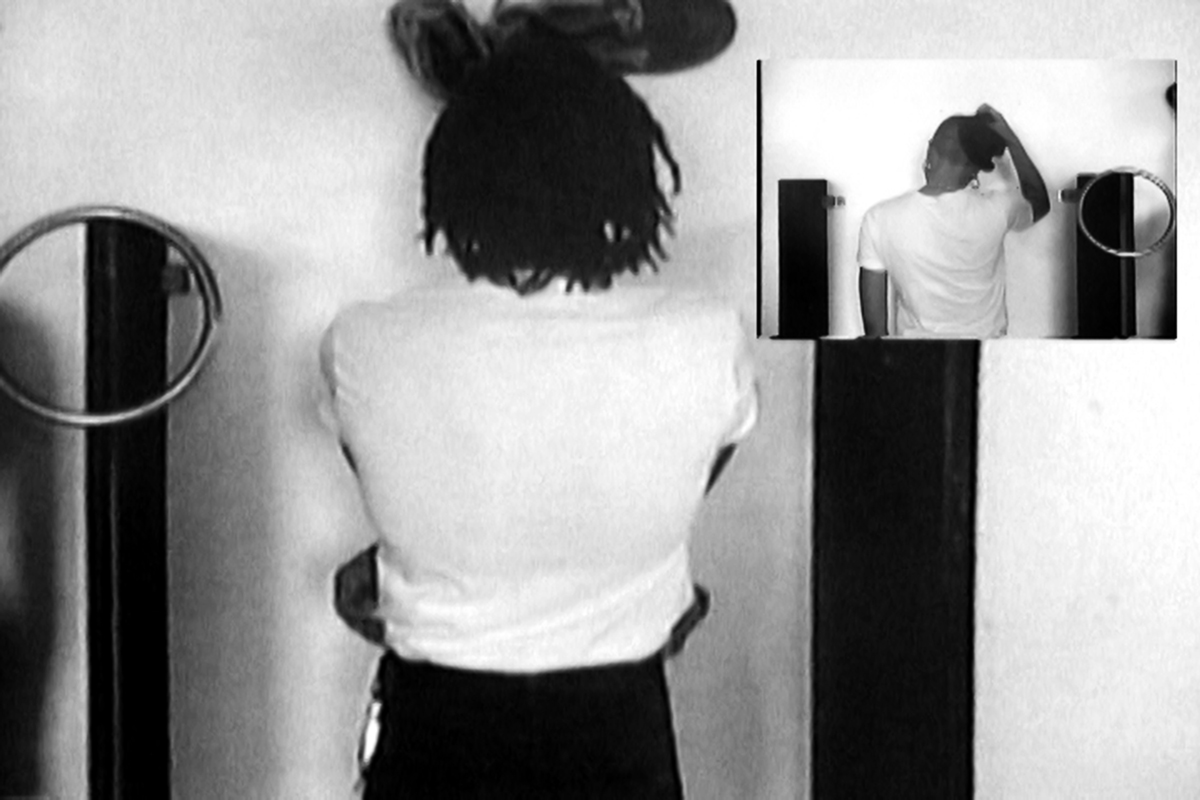

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, The Labyrinth 1.0 (still), 2017, single-channel video.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

ARTnews: All three of your practices narrate the contemporary moment from an angle that’s often been absent from the mainstream. Why is that an important and necessary approach for you?

McClodden: I really can’t make art that’s not about something that I don’t have a certain kind of proximity to. For me, it’s about honesty and trying to challenge, flush out, or disrupt the monoliths of various identities that I possess. I do it primarily for the community that’s featured within the work, and I think a lot about myself in that regard—in variations of who I am now, who I was when I was younger, and who I hope to be. It’s benefited me very much to lean into the fear around “identity politics.” I think a lot of people are afraid of it, but I see it as extraordinarily freeing and rich because it leaves a lot of space for improvisation for me. In the larger idea of the canon, it’s about disrupting and contextualizing marginalized communities in a particular way through my own hand.

ARTnews: What do you mean by “improvisation”?

McClodden: A lot of my work is informed by jazz aesthetics. If you listen to a lot of Coltrane’s later music, there are maybe only glimpses that remind you of a song. To me, that’s a beautiful space: a place to keep things fresh that will allow you to look at something differently. When I say, “identity politics,” I don’t see it as something that boxes me in. I see it as something that challenges me to be more complicated or to confront things that will push me toward an edgier place of contradiction and defying a monolith. I consider myself a bit of a formation of a riot: there are various aspects of my identity that, if you were to separate them and put them in a room, they would not get along. So, what does that mean to lean into that toxicity, which is perhaps like a bomb waiting to go off? I find that really sexy and exciting, to dig into all that, but also in that unsettled bomb, that walking riot, these things exist very peacefully, so I find that to be a space that is about improvisation.

Flash: Well, if you’re going to be someone, you have to see someone. I spent a lot of my high school years telling my mom I was coming to New York to go to the museum, and I was actually going to Christopher Street. [Laughs.] I was not seeing myself. That was before the TV show The L Word, and now there are ads on the subway with queer folks in them. It wasn’t until I got to college that I realized I was queer. My first girlfriend and I both had boyfriends at the time, and we both came out the same time. I know, for me, that it’s really important to be able to inform other queer folks, not just girls, that there are different kinds of folks. That’s one of the things I love about JEB’s work, that you photograph everyone.

If you are someone who is from a group like ours, why make the same mistakes that photographers before us have? I’m not going to name anyone, because I don’t do that, but there’s a lot of photographers still today who just photograph their community, and if their community does not include a lot of different kinds of folks, then we are still seeing the same kinds of people. I make sure I look at what the models I get. It’s not random. I look to see who is missing. I make sure I get young folks, older folks, and so on. I’m working toward really making real the history that I’m creating.

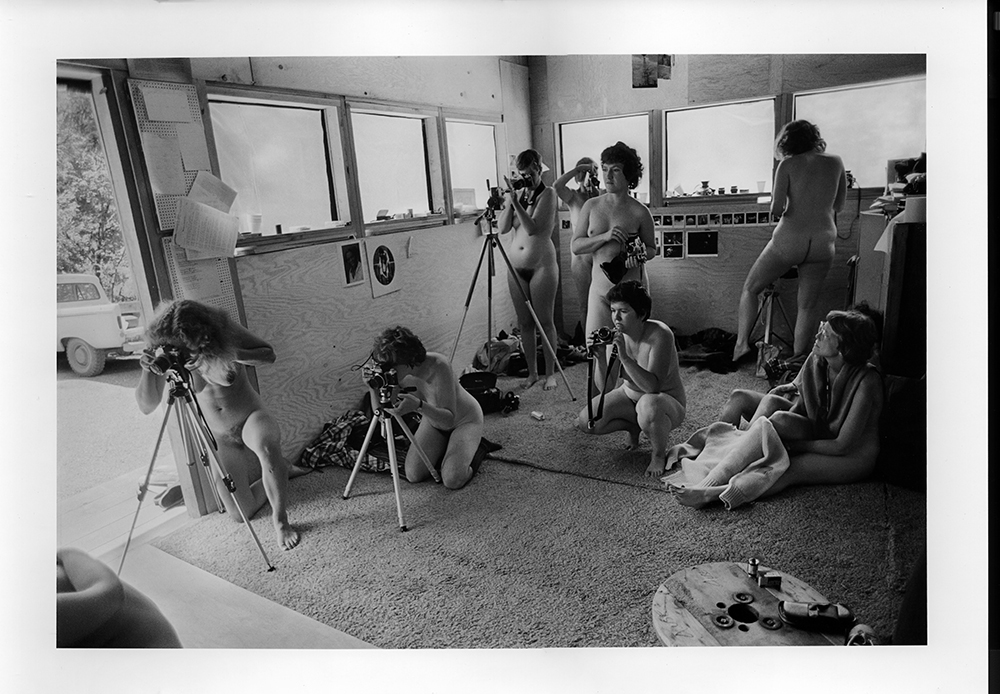

Joan E. Biren (JEB), Photographers at the Ovular, a feminist photography workshop at Rootworks, Wolf Creek, Oregon, 1980.

©2019 JEB (JOAN E. BIREN)/COURTESY THE ARTIST

JEB: When I was choosing the images for the installation that’s now in the windows of the Leslie-Lohman Museum, I had to go through all my work. It’s amazing because in the moment, you are conscious of what you are doing, but then it takes on an entirely different meaning as time passes. People pass away, trends pass away, fashions pass away. Suddenly, the work that you’ve done is more of a document of a moment than you even knew when you were making it. But when I started out, I was making images that did not exist because we needed them. When people now deconstruct them, and they think they are boring and bland, they don’t understand how revolutionary they were in the moment that they were made because there was nothing.

I thought we all needed a history. We needed to know that we weren’t unicorns—we had existed. So, I went back and researched, and came up with this slideshow, “The Dyke Show,” that included images of a photographers whom I thought were lesbians, but, of course, their personal lives were not well-documented at the time. I was going on my gut. It was so amazingly wonderful to take this slideshow around because the hunger to see these images, to know that we had a history, to know that there were lesbians before us, was so immense. Everybody was going nuts, and really, all I had done was the research.

I think that’s why you make images, because people need to see the possibilities of what they can be. They need to know their history and know they have a future being their own real selves. So many people today tell me the books that I self-published—because nobody would publish them—were literally life-saving to them. They helped people know they could come out, that there were ways to be a lesbian in the world. That’s the way you build a movement. You have to have people who are willing to be seen.

ARTnews: Who do you see as the audience for your work? And in what spaces does it get seen? Where would you prefer for it to be seen?

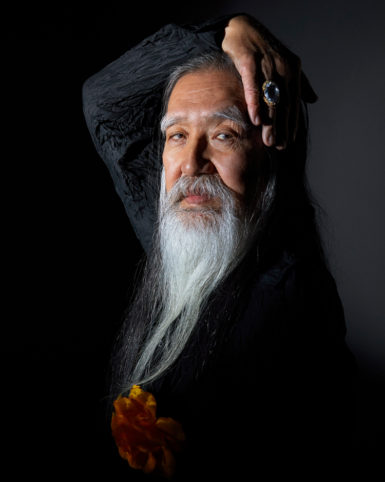

Lola Flash, Agosto, from the series “LEGENDS.”

COURTESY THE ARTIST

JEB: It couldn’t be more fabulous than for Tiona’s work to be at the Whitney and for Lola’s work to be in London at the Autograph. The more people who can see it in whatever venues, the better. Because I thought of myself more as an activist than an artist and because, in the ’70s and ’80s, no gallery was interested in the queer art, I just figured out ways to get my work circulated myself: traveling around in my VW bus with the slideshow and publishing my own books. I made postcards, and they got all over the world. People would tell me: You know, I went to Havana, and I didn’t know how I was going to come out to this person, and then I saw your dyke postcard on her refrigerator. If you make something that’s portable and cheap, then it gets around and people have it. I don’t regret that, but I’m a product of my time and my background. We have to keep pushing the work out, and that’s what these talented women are doing and it makes me really happy.

Flash: Well, without you, JEB, we wouldn’t be here. We are standing on your shoulders. The time wasn’t right when you were doing your pictures. I feel like I was under some kind of rock for 40 years, and all of a sudden, people can see me. I was feeling really invisible up until like the last three years. And I know I’m not the only black dyke photographer. I would go to the art fairs, to museums, to galleries, and I didn’t see myself. And people were saying, “Oh, there is this woman in Philly,” at the moment when I was getting really frustrated, so I checked Tiona’s work out, and I was like, Okay, she’s doing something great. And, of course, we have Zanele Muholi, whom I love to death, but Zanele’s story is a story about South Africa. It’s not our story. It’s a very different story.

I know it’s not just me and Tiona. There are lots of women artists of color out there who are doing what I’m sure is amazing work, but we just don’t get to see them. The word “his-story”—I spell it now H-I-S, because that’s another way I create my narratives. Just because our story has been neglected or misrepresented in “his-story” forever—in economics, in art, and education, every place you look—we are just not there, or we are there in a very misrepresented way. So, thank you, JEB, because we couldn’t be doing it without you. And look, there’s a lot of other older artists who I know I am standing on their shoulders. The research that you do, it’s very proven that it’s very important.

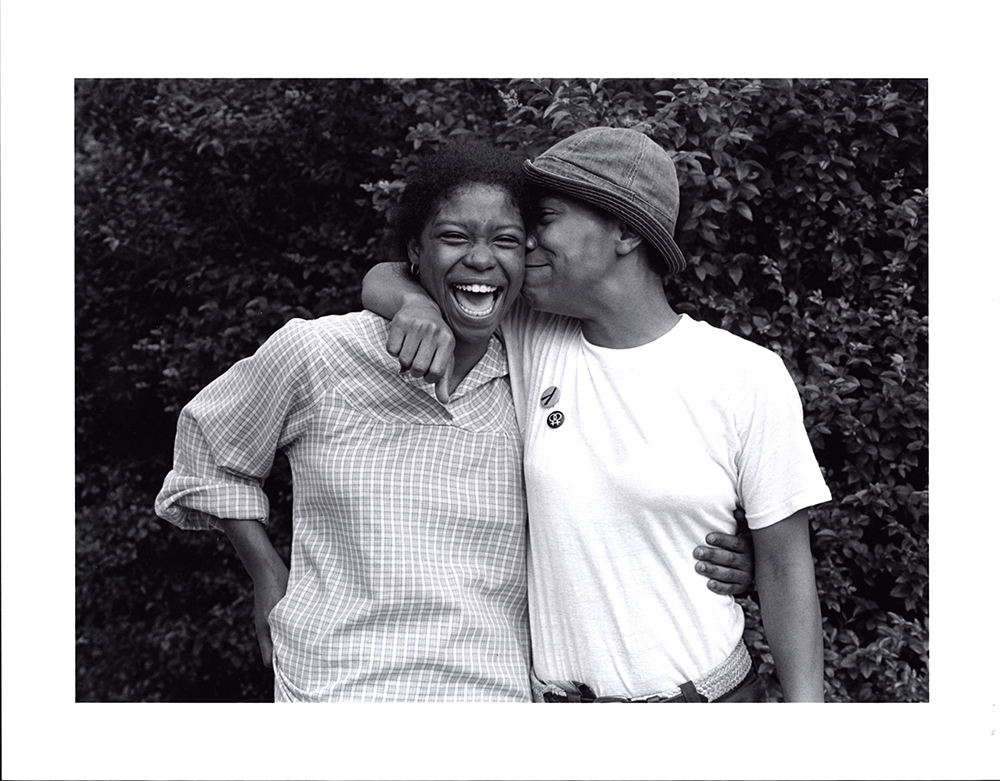

McClodden: Absolutely. I’m going to bring a couple of names into the room. Joan, seeing Stormé DeLarverie, seeing a black lesbian woman in a very casual way—those are early images that I first was able to see the connection that she had with Michelle Parkerson, someone who is big to me. My first film features Michelle Parkerson and Cheryl Clarke. Cheryl’s Living as a lesbian is where I even figured out language about what it meant to love women, what it meant to be butch, how to be okay in your body and have desires outside the norm.

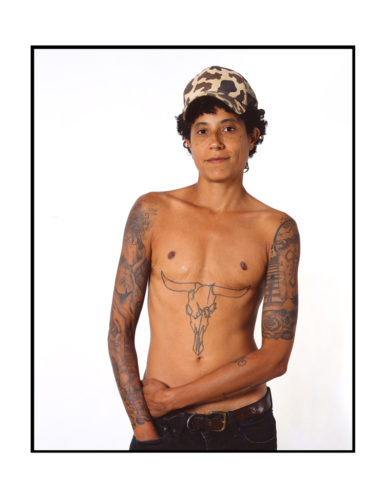

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, Se Te Subio El Santo [Are you in a trance?], 2016, digital C-print.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

So, I’ve always had a big investment in inter-generational interaction. Lola, of course, knowing your work as well has been very important for me. I think I am a bit rare because I go on the record to disclose my references. I always talk about what I’m looking at because I’m very proud to have a citational practice, something that is very much in a certain genealogy about what it means to be a lesbian woman in America.

I also think it’s important to talk about the artistic medium itself. I’m a filmmaker, but I didn’t get to see Michelle Parkerson’s films until I was in my mid- to late 20s. But photos travel differently. The way anthologies get self-published, they get into libraries. That’s how I first saw both of your images in The Blatant Image, Lesbian Folk. I just put it on Instagram to let people know that there’s other things than rainbows and whatnot. [Laughs.] It’s how you start to think about how to even write about love with women. To see the images of women holding hands, kissing each other, laying with each other, napping with each other, fucking each other. I want to acknowledge photography as one of the core elements to my practice, even though I don’t practice as a photographer. You have to see the image itself before you try to even desire for it to move. I just want to thank you all for allowing me to be able to see those images.

ARTnews: Speaking of rainbows, it is the 50th anniversary of Stonewall this year. To reference the name of a very important black women artists collective: “Where We At?” What do you make of this moment?

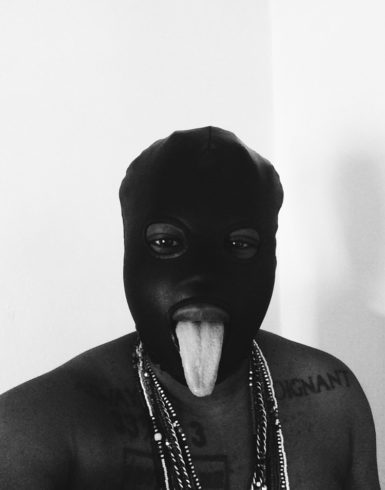

Lola Flash, Utah, from the series “[sur]passing.”

COURTESY THE ARTIST

McClodden: For a “Stonewall 50” event at the Whitney [on June 13], I get to show what I think of it. I’m focusing on the BDSM community because I’m a member of that community. The Whitney’s proximity to the Meatpacking district is very interesting because of its history with the S&M clubs that were there. I’m focusing on that community primarily because I’m seeing that the S&M community’s aesthetics are being pushed [into the mainstream] more than the respect for the individuals, their intellect, their identities, the people themselves. Quite frankly, I consider the S&M community to be the intellectual powerhouse of the LGBTQ+ community in terms of the development of literature, thought, practice, engagement in space, etc.

It’s very important for me to give space to that community by honoring a lot of core figures. I’m going to be honoring Steven Fullwood, who founded the In The Life Archive at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture [in Harlem]. I’m going to be honoring Yin Q, who is a well-known writer, dominatrix, shamanatrix, and producer of BDSM material culture through Mercy Mistress and other ventures. I’m going to be honoring Mama Viola Johnson, who has the Carter Leather Library where I’m in residence right now. I’m going to be honoring Efrain Gonzalez, a well-known photographer who has also done many tours around the Meatpacking district. These individuals are core to a certain kind of cultural retention for the SM community dynamic and intellect. The party at the Whitney is a cruise party where all codes of cruising will be recognized. I’m inviting my homies, well-known doms in the city to come and talk about sex work, the horrific things that are going on with that. I’m also going to be honoring [photographer] Alvin Baltrop posthumously. I’m going to be looking at Rachel, the first international Miss Leather, before that event even existed in 1981. Folks who are written off of the map of the larger conversation.

It’s very important to think about the S&M community because when a lot of the government-funded violence that came into New York City, those cultures shut down first. They were seen as the repository of AIDS. And so, it’s a problem to have a certain kind of aesthetic that’s pushed, a certain kind of material culture that’s not identified and contextualized, without a cultural retention or understanding of the individuals that were wiped out. When we are talking about dungeons and things like that, those places were very much about community, so you take those away, and a lot of people, like Mama Vi, then were forcibly displaced. That’s a part of the history of a larger conversation of marginalized groups within the LGBTQ+ community that I’m interested in uplifting and making sure are never silenced or dismissed in the larger conversation.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, Dom Drop (still), 2017, single-channel video.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Flash: My friend Aldo gave me this book, The Gay Militants from 1971 [about the aftermath of the Stonewall Uprising, by Donn Teal]. It’s been interesting reading about Stonewall and remembering what it really was, and about why Stonewall was the place where people that looked like us or really flamboyant gay people were being harassed all the time. There’s one part in the book where it talks about how, once the riot actually starts, all the queens are just being sort of flirtatious with the cops and everything, but that the guys who could pass were like, Oh, it looks like it’s got a little bit too heated, so they just slipped out of the picture. There’s been a lot of mistakes about [the historical record of] Stonewall, and I think that people are working toward remembering who the warriors actually were. Stonewall was where anyone who didn’t look straight went. Plus, there were a bunch of young kids who were homeless because they had been kicked out of their homes. That’s why it was such a place that there was so much agitation around it. I didn’t know that until I was in my 20s, or what Pride meant and why it was the 28th of June. I’m finding now that more young folks—the new generation—seem to be more interested in the history.

One thing I do get kind of angry about around this time of year is that all these Pride parties now just get more and more incrementally expensive. And it’s funny, I’ll be on the bus, and I’ll hear people say, “Watch out for Fifth Avenue because there’s a parade,” and I get all excited because I’m just like, “Yes! We are going to ruin everyone’s day, as far as their transportation.” Then I start to think, Why haven’t the gay clubs had a sliding-scale entrance fee forever? The guys have known forever that they make more money than us because they are men, so why hasn’t that been something that has just been a part of the clubs? I get really pissed off because I see these parties at different clubs with DJs, and they look fun. I’m a teacher. I can’t afford those things either. I wouldn’t want to go, but just politically speaking, it doesn’t seem right that these kinds of like distinctions aren’t made for our community.

My hope for this liberation that we are continuing to go through is that our community becomes more like how we were in ACT UP [the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power]. When we were in ACT UP, we didn’t know who was going to die next. People were not being awful toward each other. It was just like, “You can help. You’re a photographer, you’re a club kid.” Everyone had a position because we were going to make this virus go away. We haven’t done that yet, but we’re getting closer—the drugs are better, and one person was cured. My hope is that, one day, we find love for each other and we are not being so critical about who we are. We are family, and we should be like a family that works well together, not like a dysfunctional family. We should love each other for who we are.

Joan E. Biren (JEB), Gloria and Charmaine, 1979.

©2019 JEB (JOAN E. BIREN)/COURTESY THE ARTIST

JEB: Stonewall was not the beginning of the movement, but it was a very important turning point in the creation of an LGBTQ+ movement. It was a liberation movement, and that meant something particular because we were in the middle of a world that had liberation fronts in Vietnam, Cuba, and other places. Liberation had a meaning. It wasn’t up in the air: “Yay, we are going to be free.” It was a political organizational front to move us toward a different kind of freedom in a different kind of system than the one that we are living in now. Immediately, there became a split in the movement between the liberationists and the assimilationists, who felt that LGBTQ+ people just wanted the same rights as everybody else. We called it “the suits versus the streets.”

Now in this particular post–same-sex marriage country that is being ruled by an evil despot, I think everybody needs to understand that all the gains that the assimilationists won through being in the system are being thrown away every day—and every other right that we have can also be thrown away. We are seeing this with women with abortion rights, with gay people about whether we can keep our children or not. And we never even got anti-discrimination laws in employment, we never even got that far in this country as a whole. People who have felt what I would call a false sense of security about where we queer people fit in the world had better think about how to run a liberation movement.

One of the ways that we have to do it better than we did it at other points is that we have to understand that it’s not just queer people who are under attack. It’s people of color. It’s Muslims. It’s immigrants. It’s all kinds of marginalized people in this country. We all need to be working together because if we can form a strong coalition movement, which is hard to do, but we need to do it because the threat is that big. There are more of us, and we can be really strong and we can really do it. So that’s where I think we are right now. The Queer Liberation March—it’s about liberation, it’s non-corporate, non-police, and it will give you an idea of the difference between where we are in 2019 and where we oughta be in 2019. We can be a strong liberation movement, and we must be.

[ad_2]

Source link