[ad_1]

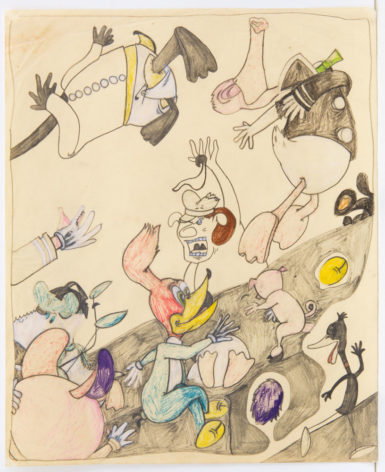

Susan Te Kahurangi King, Untitled, 1967–70, graphite and colored pencil on paper.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Like many children, Susan Te Kahurangi King spent hours drawing with crayons when she was young, filling entire pages with bold lines. Unlike many children, she was identified as being an artistic prodigy early on, lauded at the age of five by a primary school teacher for her complex figures. The eldest of 12 children, King was encouraged by her parents, who provided supplies and a dedicated space to draw at home, and decades later, she has become one of today’s most celebrated draftspersons.

Born in Te Aroha, New Zealand, King, who is now 68, has produced several thousand drawings over her career, most of which was spent in relative obscurity. But that all changed when the artist Gary Panter caught wind of King’s output. In 2013, he saw some of her works, filled with cartoony pop-cultural references, on Facebook, and shared images with curator Chris Byrne, who began working with King’s family to exhibit her art around the world. It has since appeared at New York galleries like Andrew Edlin and Marlborough Contemporary, and is currently the subject of a major survey at Chicago’s Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, where more than 60 drawings from 1958 to 2018 are on view through August 4.

“She’s really a master at reconfiguring objects and items from popular culture and coming up with scenes whose meanings are left to the viewer to determine,” Alison Amick, an Intuit curator who worked with Byrne to organize the show, said. “The more you look at Susan’s work, the more you can uncover.”

Susan Te Kahurangi King, Untitled, ca. 1965, graphite and colored pencil.

COURTESY THE ARTIST/COLLECTION OF KAWS

Organized chronologically, the show details King’s unusual, evolving interests. At age seven, she was obsessed with Donald Duck, twisting his body into pretzels, and cropping and arranging his form into witty, crayoned grotesqueries. They presage later drawings, rendered in graphite and colored pencil, that feature complex mishmashes of planes and perspectives. In them, personas like Woody Woodpecker, Bugs Bunny, and a grinning clown (the mascot of Fanta soda) prance around, each seemingly lost in their own worlds.

Dense labyrinths of restless characters such as these were key during what King’s younger sister Petita Cole refers to as the artist’s “rich drawing period,” during the late ’60s and ’70s. Curiously, amid the bodies collapsing or colliding with one another, King often left a section of her paper canvas entirely white, making the force of her intricate lines all the more palpable.

Many critics who’ve written about King’s work have ascribed her drawings’ mysteriousness to the fact that she stopped speaking entirely at the age of eight, for unknown reasons. It can be easy to fixate on this detail of her biography, especially given her dramatic last words, spoken to her grandparents after a funeral: “Dead, dead, dead.” But the impulse to analyze the implications of this silence can limit our interpretation of the drawings, according to Cole, who cautions against reading her sister’s work as a form of communication. “I think it’s a process and an expression of herself, of her feelings, of her understanding of her fascinations,” Cole said.

For visitors who seek some guidance through King’s topsy-turvy world, the Intuit show pairs her drawings with a display of photographs and objects from Cole’s personal collection, like plastic cars and a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle figure—items that King would have seen around her house or on trips with her family. There are utilitarian objects, too, like a rubber bathing cap and a metal meat mincer that appears in some of King’s drawings as the heads of figures. A keen observer, she sometimes startled her family with some of the things she depicted, such as a bevy of phalluses.

“She has this amazing memory to record details of all the things you see in her drawings,” Cole said. “She only needs to see something once, and it’s in her head.”

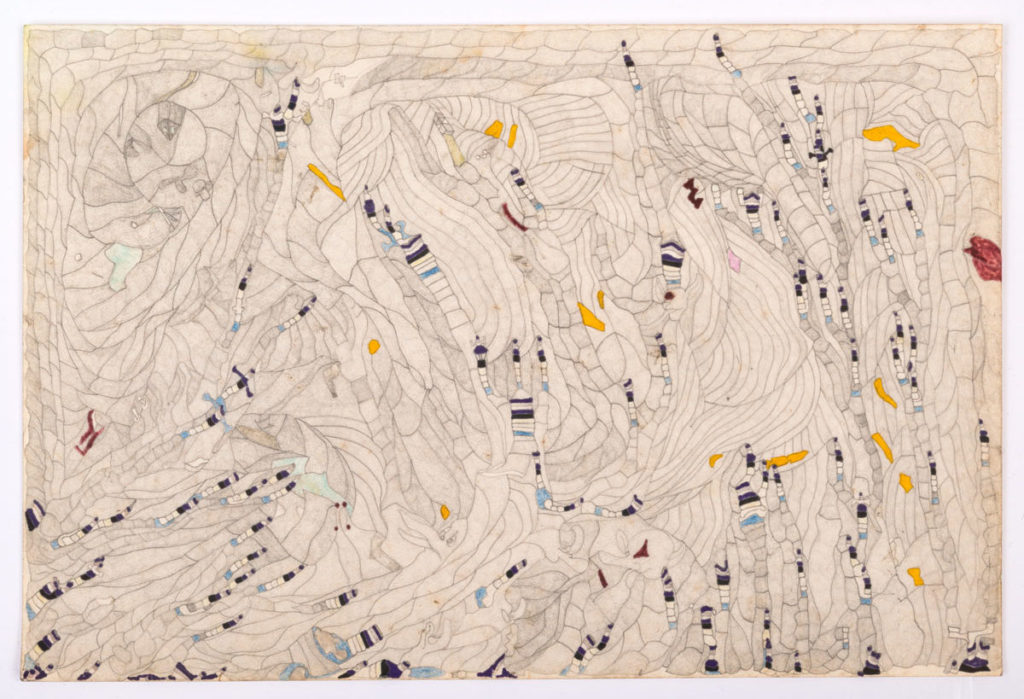

Susan Te Kahurangi King, Untitled, 1985–89, graphite, colored pencil, and felt pen on paper.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ANDREW EDLIN GALLERY, NEW YORK

Cole often describes her sister’s practice as “compulsive.” Even at the beach, away from art supplies, King would draw lines in the sand, as captured in a lovely black-and-white photograph in the exhibition. But her prolific art-making came to a halt in the early ’90s, when she stopped drawing entirely. According to Cole, King was in “a low state, not only psychologically but also physically.” Many of her siblings had also left the house. She started making art again in 2008, after family members implored her times to pick up a pen. In the interim, Cole had started teaching children with autism, and she noticed similarities in the behaviors of her students and her sister; King was later diagnosed with the disorder.

There’s a marked stylistic shift in the artist’s works from the last decade. Done largely in ink, graphite, and felt pen, these pieces no longer have a cartoonish quality and are, instead, highly abstract. King’s distinct figures have disappeared, replaced by energetic pathways of color that freely crisscross or snake around each other. It’s less easy to get lost in these pictures, but they are still skillfully rendered and their compositions are clever.

Incredibly, King’s family kept every one of her childhood drawings. Her late grandmother saved her early work, and she even went so far as to date and describe these pieces in diary entries. Cole has continued those efforts, and since 2005, has been methodically archiving her sister’s creations, processing box after box until the work is done. “There’s a lot more to come,” she said.

[ad_2]

Source link