[ad_1]

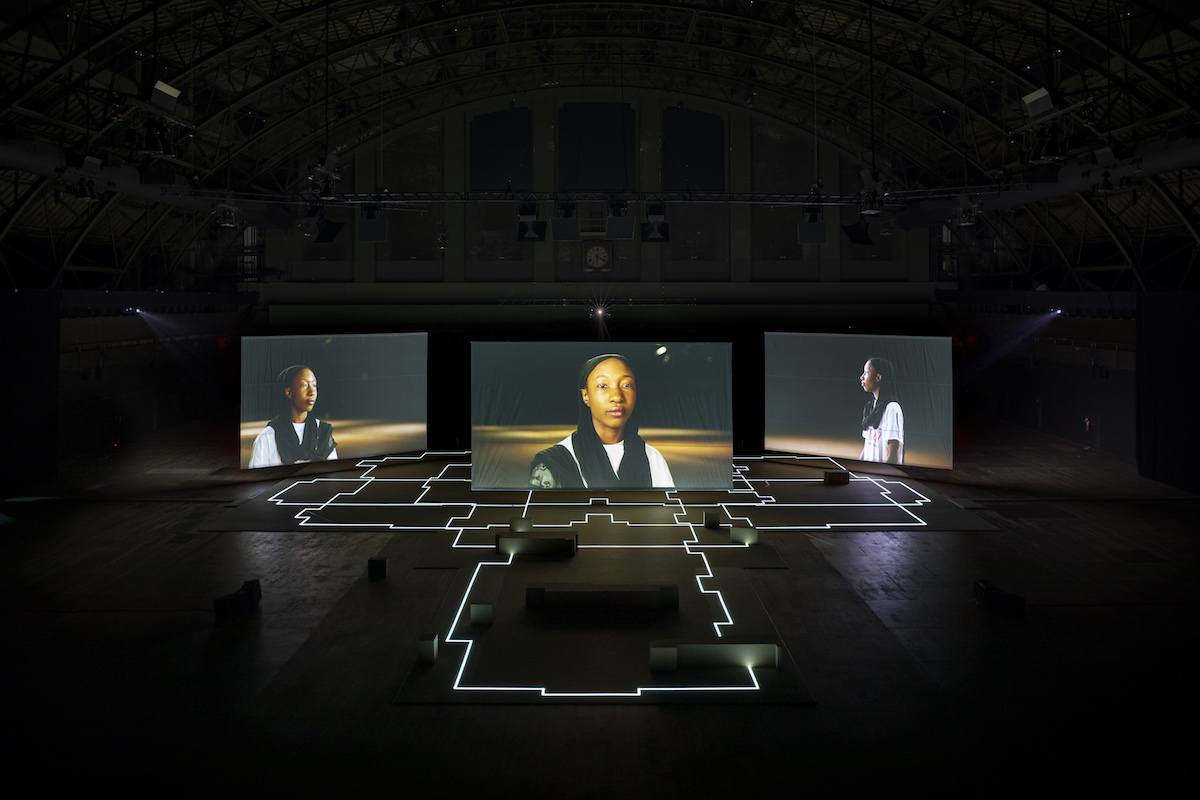

Hito Steyerl, Drill, 2019, three-channel video installation, 21 minutes, HD video. Installation view at Park Avenue Armory, New York.

©JAMES EWING

“Historically, museums have always been battlefields,” Hito Steyerl once told a crowd at a summit convened by the activist-art organization Creative Time. “They have been torture chambers. They have been sites of executions.” That was in 2012—which feels like eons ago in the current context of protest surrounding Warren B. Kanders, the Sackler family, and other matters haunting institutions of all kinds. One could say the times have changed, but thankfully, Steyerl’s work—which tends toward incisive videos and installations that tease out connections between global conflict, digital technology, violence, capitalist structures, and art—has not. I’d put it another way: the times have caught up to Steyerl.

At the Park Avenue Armory in New York, the Berlin-based artist has debuted one of her most exceptional works to date. In a survey curated by Tom Eccles (opened this week and running through July 21), a centerpiece titled Drill takes the form of a three-channel video installation with stylized documentary footage of a historian, activists, and a marching band in a work that homes in on gun violence in America, with a consideration of the Armory and the founding of the National Rifle Association. Added to that is a focus on the venue itself: a cavernous building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side with transcendent architecture and luminous features conceived by a team that included Louis Comfort Tiffany—and also an ugly history connected to militarism and wealth in a city long separated in terms of rich and poor.

Steyerl’s skill at editing, honed over close to two decades, does not fail her as Drill expertly weaves between the history of its setting and gun violence at Columbine, Parkland, and Newtown. The majority of the video features its protagonists walking or marching through the Armory, explicating its history and telling Steyerl of the resultant trauma of recent tragedies.

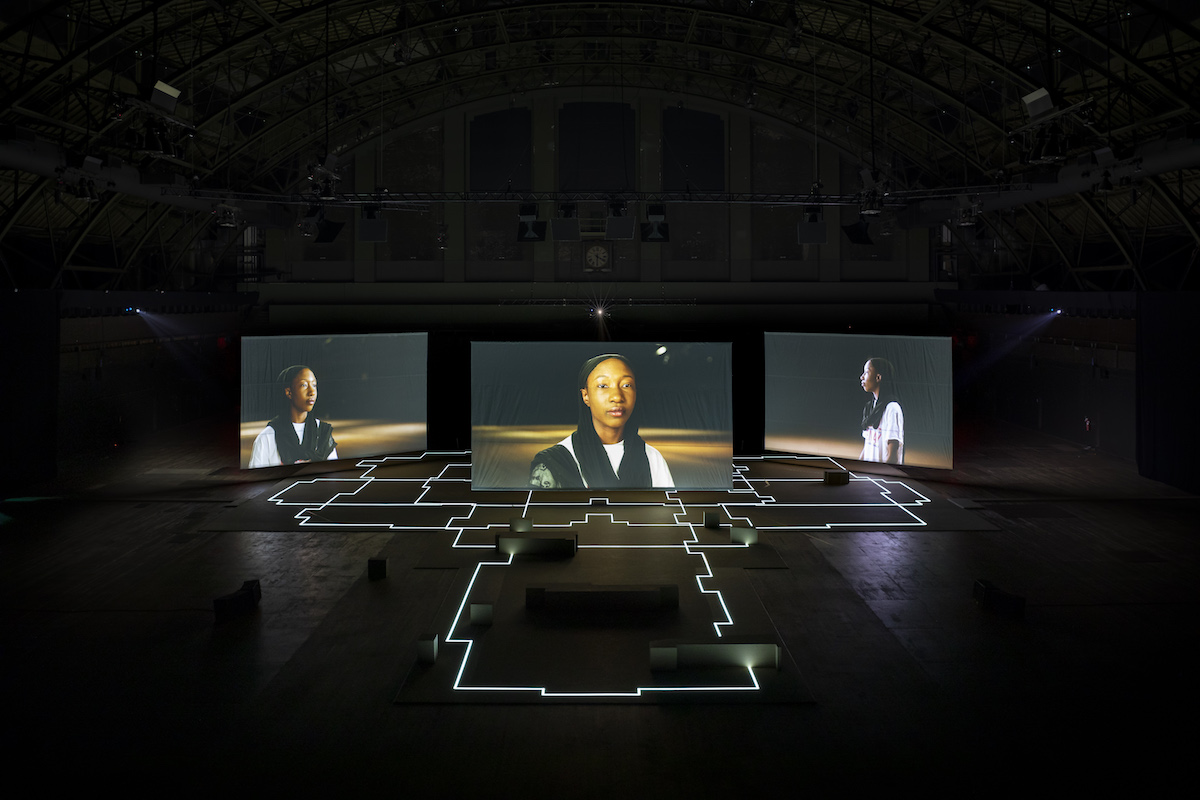

Hito Steyerl, Is the Museum a Battlefield?, 2013, lecture and HD video. Installation view at Park Avenue Armory, New York.

©JAMES EWING

“Historically, this building was definitely beautiful, but also definitely a fortress,” a historian tells Steyerl at one point. The guide holds up a flashlight to paintings hanging on the Armory’s walls and points out early advocates of guns—as well as bullet holes from shooting exercises in the building’s basement. The dank subterranean setting and Steyerl’s horror movie–like lighting give the video a haunted quality. That effect is amplified by occasional interruptions by a marching band that parades around the space while playing abstracted sounds of carnage via a score composed by Antonio Medina and Thomas C. Duffy that corresponds with data points related to mass shootings in America.

Though the work doesn’t quite stick the landing in a corny finale with edits of footage of anti-gun activists superimposed into the frames of old portraits in the Armory, Drill is nonetheless a master class in how to draw links between seemingly unlike ideas. Created in the tradition of Harun Farocki and Chris Marker, it’s yet another essential work from Steyerl—and a must-see in an otherwise quiet summer season in New York.

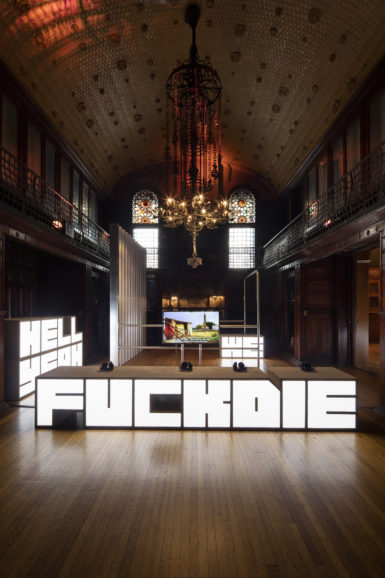

Hito Steyerl, Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, 2016, 4 minutes, HD video, environment. Installation view at Park Avenue Armory, New York.

©JAMES EWING

So are many of Steyerl’s other recent works in the show. Thankfully the Armory has taken the occasion to broadly survey Steyerl’s output via eight works dating back to 2013. Included are a 2013 video installation titled Is the Museum a Battlefield?, drawing on a past lecture and including a giant bench for viewers fashioned with sandbags, and one of Steyerl’s most fascinating works: Broken Windows (2018–19), which links an activist artist in New Jersey who paints over broken windows with scientists who smash panes to train artificial intelligence to understand the sound of shattering glass.

Steyerl’s work can be wonderfully funny too, and fortunately the Armory is also showing some of her more lighthearted work. One of the best pieces in the show is Hell Yeah We Fuck Die (2016), an installation addressing odd power dynamics that guide human relationships with robots. (It was also shown at the 2017 edition of Skulptur Projekte Münster in Germany.) Videos scattered within the work—which also features the title rendered in a stylish font as neon sculpture—show a giraffe-like avatar ambling through a vacant digital void. The figure is pelted with mustard-colored cubes and speared with red beams; afterward, its body briefly lies impassive, as though slain by digital weaponry. What might be otherwise just weirdly amusing transforms when Steyerl reminds you, via footage appropriated from product-testing labs, that scientists really do subject robots to bizarre forms of violence.

With other works including a video installation addressing the Iraqi National Observatory and another that weaves together a plan by Saddam Hussein to build a would-be Tower of Babel with a Ukrainian video game company and the concept of offshore assets, the sensation of watching Steyerl’s videos can feel like swimming through a sea of interrelated ideas and structures that inform 21st-century life.

In spite of what that might suggest, however, Steyerl’s Armory show remains curiously hopeful. Along with Drill, she’s also debuting Freeplots (2019), a sculptural installation that melds boxy wooden forms with horse-manure compost and flowers from a garden in Harlem. At a press conference marking the opening of the show, Steyerl spoke of learning, much to her surprise, that she had once made money through a sale of work that had ended up in a freeport, a storage facility that hosts collectors’ holdings free of taxes. Some of her windfall, she said, was put toward the creation of Freeplots. When I visited the show, a few purplish flowers had begun blooming. One can only assume more will follow.

[ad_2]

Source link