[ad_1]

They are the living embodiment of joy.

In Soweto,

a township in Johannesburg, South Africa, a group of animated young girls

warmly receives visitors. The girls greet guests with jovial smiles and open

hands. Once these ambassadors

have each selected a friend from the

visiting group, they lead a tour.

This tour

is unique because the girls do little talking and instead find other ways to

communicate, mostly through hand gestures and giggles.

Truly,

these girls bring life to the area around them. When their infectious laughter permeates

the air, it creates vivid imagery of joy, wonderment, curiosity, and glee.

This

opening scene is a snapshot of what South Africa can be.

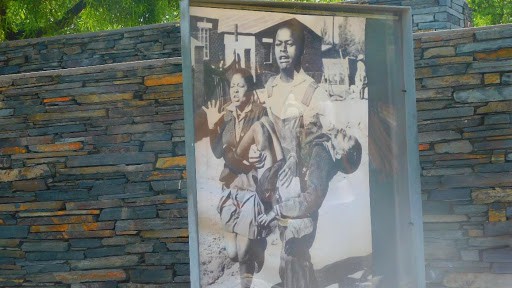

South Africans born after 1994 are part of the “born-free”

generation because they are free of the Apartheid system. Although Apartheid

has been abolished for 25 years, Black South Africans are still feeling its

effects.

“The

socioeconomic impacts of racism are not ending now because a majority of the

Black South Africans still live under appalling conditions,” said Beatrice

Akala, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Johannesburg.

“We have the issue of land that is quite deep

in this country… the majority of South Africans, Black South Africans, don’t

have access to land,” she added.

This can be

observed firsthand in places such as Elias Motsoaledi, an informal settlement where

the young girls conduct their tour. Black South Africans formed these settlements

after the government failed to redistribute land it had seized during

Apartheid.

The Native Land

Act of 1913 delegated 7 percent of arable land to Black South Africans and delegated

most of the fertile land to White South Africans, according to South Africa history online, a nonprofit organization that

tracks the country’s history.

One hundred and six years later, efforts are being made to reverse this decision.

Just last

week, South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa received a report that promised

“a fair and equitable land reform process that redresses the injustices of the

past,” Times Live, a prominent news site

in South Africa, reported.

The Native Land Act was not the only legislation to advance Apartheid.

If this

were 1954 South Africa, Black South Africans would be protesting the Bantu

Education Act of 1953. This

act created segregated schools in Bantustans, or areas designated for Black

South Africans, where students would be taught in their native languages,

although the curriculum would be in English and Afrikaans. In addition, they

would learn only skills that could benefit the White minority in power. To

Akala, Bantu education was a tool to make Black South Africans more suitable

for servitude. “Bantu education was mainly for the Black people to make them

not see beyond their horizons,” she said.

Sandra Roberts, D.Litt. et Phil., also said something to this effect. She is a researcher for frayintermedia, a “pan-African communications company,” according to its LinkedIn profile.

Roberts

said educational barriers persist for Black South Africans because of Apartheid

and Bantu education. “A lot of the legacy continues and has not been

successfully addressed even in the 20-plus years since democracy. … Our Grade Nines

don’t compare with Grade Nines in other similar countries; [ours] are actually

two years behind in math and science,” she noted.

Other research

has pointed to similar disparities in education, especially for girls.

Nomvula Mokonyane, minister of Water and

Sanitation in South Africa’s parliament, wrote, “Only 22

percent of African and coloured [sic] women have obtained Grade 12 whereas the

figure is 35 percent and 40 percent for Indians and Whites, respectively.”

This racial

distinction is important, but gender and class distinctions are also important

to account for, since Black women experience intersectional oppressions, Akala

posited in a research

essay.

She wrote, “Black

women, who are the main target of this article suffered triple marginalisation (sic)—

race, social class and sexism.”

When

discussing this research in person, Akala added, “It’s a whole lot of layers of

marginalization that came with the Apartheid system.” Black

South African girls and women, it seems, face subjugation within a larger system of subjugation.

“If I said,

‘No, I’m not stopping here,’ then [my father] made sure I went to the next

level. But that was not the case with most of my friends in my home village,”

recounted Akala, who is originally from Kenya. “I know of very brilliant girls

who did not get a chance to go on with education.”

Akala realized she was the exception, not the

rule. So when she later pursued a Ph.D. in education from the University of

Johannesburg, her dissertation focused on gender equity in South Africa’s

education system.

While Akala fought at a microcosmic

level, there are also large-scale efforts to improve the education of girls and

women in South Africa.

In 2003,

the Girls

Education Movement, which sought to improve girl child education throughout Africa,

trickled down from Uganda. That same year, the “Take a Girl

Child to Work” initiative was launched. This is an annual event during which companies

will invite girls from different schools, usually disadvantaged ones, to their workplaces

for the day.

More

recently, Judy Dlamini, M.D., became

the first Black woman chancellor at the University of Witwatersrand. To some, her chancellorship signals a step

forward for South Africa.

“It’s

exciting. It’s really exciting times,” noted Reatgile Mosehla, a student at the

university. “South Africa is clearly changing.”

[ad_2]

Source link