[ad_1]

Deep in the bunker, at Basel in June, with a sprawling sculpture by Anne Speier at center, presented by Vienna’s Galerie Meyer Kainer.

PHOTOS: ANDREW RUSSETH/ARTNEWS

[Follow all of our coverage from Art Basel 2019.]

June, an upstart fair in Basel, may be less than five minutes by foot from Art Basel, but it feels like it’s on a different planet. It’s tucked deep in an underground bunker, next to a verdant soccer field and a lush community garden. Instead of Art Basel’s roughly 300 exhibitors, June has just 14, and they are arrayed throughout the Herzog & de Meuron–designed space so that it feels more like a loose exhibition than a trade show. Founded by two dealers, Copenhagen’s Christian Andersen and Oslo’s Esperanza Rosales (who runs VI, VII gallery), it’s a laid-back addition to the high-pressure Basel landscape.

Works by Sky Hopinka at the Green Gallery, Milwaukee, which also has works on view by Michelle Grabner—what appear to be small abstract paintings that are, in fact, bronze casts.

The space is quiet, ample, and well-lit, and there is a lot of art to enjoy—a welcome mixture of recent creations with some art-historical nuggets scattered throughout. (Having said all that, I do feel a bit sorry for the dealers who have to spend all day—from 1 to 8 p.m.—cooped up in this chic concrete-walled subterranean lair.)

Tobias Kaspar at Oslo’s VI, VII.

Hannah Hoffman Gallery, of Los Angeles, has put together a highly unusual two-person display: works by the storied Belgian poet-turned-artist Marcel Broodthaers (including a sculpture with his classic cracked eggs) and videos by the piercingly astute Los Angeles artist and teacher D’Ette Nogle (one compiles movie clips of women giving birth or dealing with pregnancy in various ways). I would never have guessed it, but Nogle, who was born in 1974, and Broodthaers, who died on his 52nd birthday in 1976, make a fine duo.

A partial view of the paintings by Lea von Wintzingerode on view at Lulu, in town from Mexico City.

Misako & Rosen, from Tokyo, has another cross-generational pairing, in the form of a multifaceted collaboration between the veteran Hisachika Takahashi (whose remarkable career has included a stint cooking at Gordon Matta-Clark’s Food restaurant in SoHo in the early 1970s) and Yuki Okumura. Their display centers on the former artist’s 1967 show at the pioneering Antwerp venue for conceptual art Wide White Space, and among its offerings are a wonderfully decorative 1966 painting by Takahashi (think Konrad Lueg with more electric colors), as well as work the two made together.

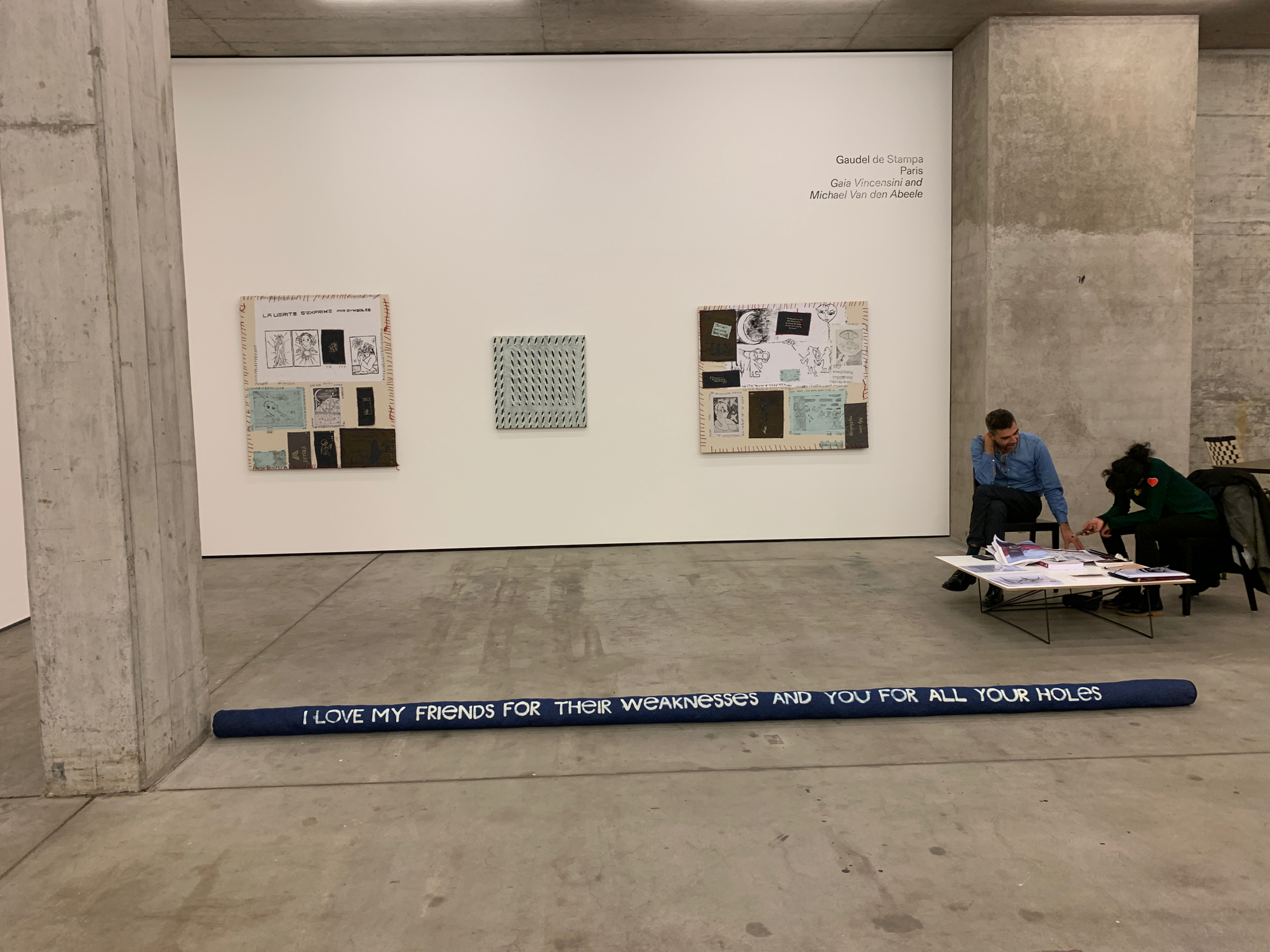

Works by Gaia Vincensini and Michael Van den Abeele at Gaudel de Stampa, of Paris.

Also taking the two-person approach is the Green Gallery, which is visiting from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. On one wall are tiny, intricate Michelle Grabner works that resemble paintings but are, in fact, bronzes—they are tempting to read as little rejoinders to the ostentatious, gargantuan cast paintings that Rudolf Stingel is showing a few kilometers away at the Fondation Beyeler. And on another wall are bewitching inkjet prints, just under three-feet-square, that artist and filmmaker Sky Hopinka makes by arranging color transparencies on the bed of a projector and shooting the resulting compositions. They show landscapes, skies, and a few people—sometimes overlapping, sometimes with blank spaces, as if we’re seeing memories being pieced together. The artist also etches short phrases onto them. “The light was blue and so were you,” one reads.

Hans-Christian Lotz at Christian Andersen, of Copenhagen.

Meanwhile, Mexico City’s Lulu gallery has lined a long corridor with paintings by Lea von Wintzingerode, who uses unconventional (but quite pleasing) color palettes and techniques (diluting oil to such a degree that it resembles unwieldy watercolor) to paint brushy portraits, landscapes, and interiors. Von Wintzingerode has an impressively light touch, and she uses it toward deceptive ends: there’s a psychological intensity to many of these pieces, especially in the case of an oval tondo that shows a faceless figure that seems to be floating between two beds. Its border is marked by quick brush marks, as if we’re looking out, through an eye, past eyelashes.

Colette Lumiere’s Justine and the Boys (1979), screening in a presentation by New York’s Mitchell Algus.

At the more art-historical end of the spectrum, New York’s Mitchell Algus gallery is showing Colette Lumiere’s 1979 film Justine and the Boys, which features appearances by, among others, then-unknown artists Jeff Koons (sipping a Heineken at one point) and Richard Prince, as well as Colette herself. They’re all lounging in the artist’s Downtown Manhattan loft. Though it’s a bit difficult to sit through, it’s a fascinating period piece. Who would have thought that awkward guy in a suit would have one of his sculptures go for $91 million exactly 40 years later? No one. And so, seen in the context of Basel, it is a reminder that fame and the market work in mysterious and unpredictable ways. Best to just buy—or simply enjoy—the art you like, and see what happens.

Algus is also on hand as an artist, showing vitrines with fabric sculptures.

Behind the bunker, a beautiful garden, where freshly baked pizzas—and beverages—are on offer.

[ad_2]

Source link