[ad_1]

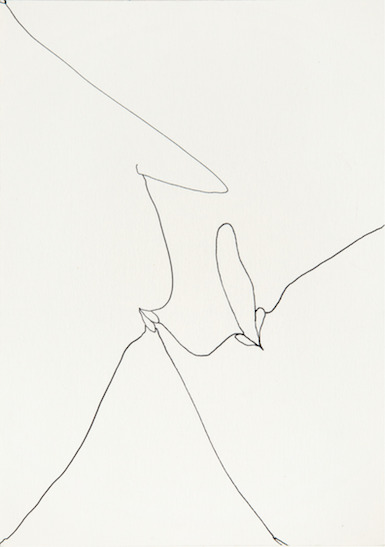

Huguette Caland, Bribes de Corps, 1973.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Huguette Caland’s painting series Bribes de Corps (Body Parts) could very well be an expression of orgasmic pleasure. The canvases painted in the early 1970s are filled with bright, sunny bursts of vibrating color. Organic forms—abstract and elemental—evoke feminine curves, slits, and points of embrace. Created in the run-up to the Lebanese civil war as the Beirut-born but relocated artist found her voice in Paris, the works reflect Caland’s essence as a free, fun-loving woman detaching herself from the burdens of patriarchal tradition and the conventions of genre. While hints of the Mediterranean Sea remained, Caland liberated her paintings from a sense of place and opted instead to search deep inside her own soul and desires.

“Art is not a part of my life; it is my whole life,” Caland told her friend, the writer Helen Khal, for her 1987 survey book The Woman Artist in Lebanon. “I’ve never analyzed my creative intention. I know only that I want to determine a point of emotion in the painting or drawing, and that I am absorbed by an exploration of the sensual possibilities of the human body.”

Huguette Caland, Flirt II, 1972.

TATE

Now at the age of 88, after moving from Beirut to Paris and California and eventually back to Lebanon, the remarkably original Caland is finally receiving some of the attention she deserves. A new solo show at Tate St. Ives, in an English seaside town favored by artists going back to J. M. W. Turner, is an homage to Caland’s unapologetic feminism and lust for life, focusing on the first two decades of her career from the 1960s to the ’80s.

“It’s her first museum solo show and that’s OK,” Brigitte Caland, the artist’s daughter, told me from Beirut. “Things happen when they happen. The curators have really understood the happy and whimsical side of my mother. Everything is happy. The location is gorgeous. My mother loves the sea and the space is sublime.”

Caland’s daughter, who manages her mother’s work and spoke for her as she is no longer able to communicate with ease, continued, “An exhibition is so personal and physical, not only intellectual. These works are mischievous, fun, and very meaningful. The work radiates a sense of freedom, courage, humor. When my mother left Lebanon, she left her social status, her husband, her home, her sense of stability behind. These are important years.”

The Tate exhibition shows the first works that Caland made in Beirut in the mid to late ’60s as well as paintings, drawings, and textiles produced in Paris, after she left her family to focus on her art. Born in 1931 as the daughter of Bechara el Khoury, Lebanon’s first president after the country declared independence from France after 23 years of rule, she decided at age 12 that she wanted to be with Paul Caland, the nephew of the founder of the pro-French newspaper L’Orient and a political rival of her family. The couple married when she was 21, and they both took other lovers as they raised a family.

Installation view of Huguette Caland’s show at Tate St. Ives.

TATE

Caland traveled and took up an interest in painting. In 1964, at the age of 33 and the mother of three children, she enrolled in the American University of Beirut’s fine art program. She cared for her ill father for several years, and, after he died, Caland created her first painting, Soleil Rouge (1964), a monochromatic surface revealing blurry lava-like orbits. Shattered but also liberated by her father’s death, Caland left her old life behind to dedicate herself completely to her art, and her early work’s radical abstraction marked the beginning of a lifelong exploration of the pure power of line, form, and color.

Huguette Caland, Tête á Tête Dress No. 3, 1971, 1973.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

After moving to Paris in 1970, Caland emboldened her minimalist lines, deepened her experiments with color and light, and communed with like-minded artists and intellectuals like the Romanian sculptor George Apostu, who was her lover, and the Syrian poet Adonis. While always connected to her homeland and family, distance and the thriving intellectual creativity of the French capital allowed her to deepen her experiments. There she created several seminal paintings on show at Tate St. Ives, including the semi-abstract Visage Sans Bouche, Bouche Sans Visage (1970–71) and the somber wartime work Guerre Incivile (1981), which depicts amputated figures in the artist’s sensual style. She also painted abayas (traditional Arabic caftans) that she began wearing after her father’s death with her whimsical shapes and characters. Pierre Cardin, upon meeting her, ordered a collection of custom dresses made in such a fashion.

Anne Barlow, the director of Tate St. Ives and curator of the Caland exhibition, spoke of due attention for the artist’s work in the context of her institution’s recent focus on women artists, including Rebecca Warren, Virginia Woolf, and Barbara Hepworth. “Everyone realizes that this is such a huge moment for Huguette,” Barlow said, alluding to important recent Caland shows such as a 2014 exhibition at Lombard Freid Gallery in New York and appearances at the Beirut Exhibition Center (2013), Prospect New Orleans (2015), Made in L.A. (2016), the Venice Biennale (2017), and the Sharjah Biennial (2019). “People are drawn to the sheer beauty and power of her work. It’s not possible to say that the work illustrates a particular style or genre because her style is very visibly hers. She’s important not only because of the formal beauty of her work but the way in which she uses paint to create these incredible forms and light.”

For Barlow, the recent expansion of art-historical narratives to include broader geographies, gender identities, and genres has been crucial. “The topic of female originality and looking at various art histories that make up a larger view is important,” she said. “There is a real need and interest in critically engaging with these histories.”

There is also a need to expand critical fields to engage with more intimate experiences of art. As Caland herself once said, years ago, “I love every minute of my life. I squeeze it like an orange and I eat the peel, because I don’t want to miss anything.”

[ad_2]

Source link