[ad_1]

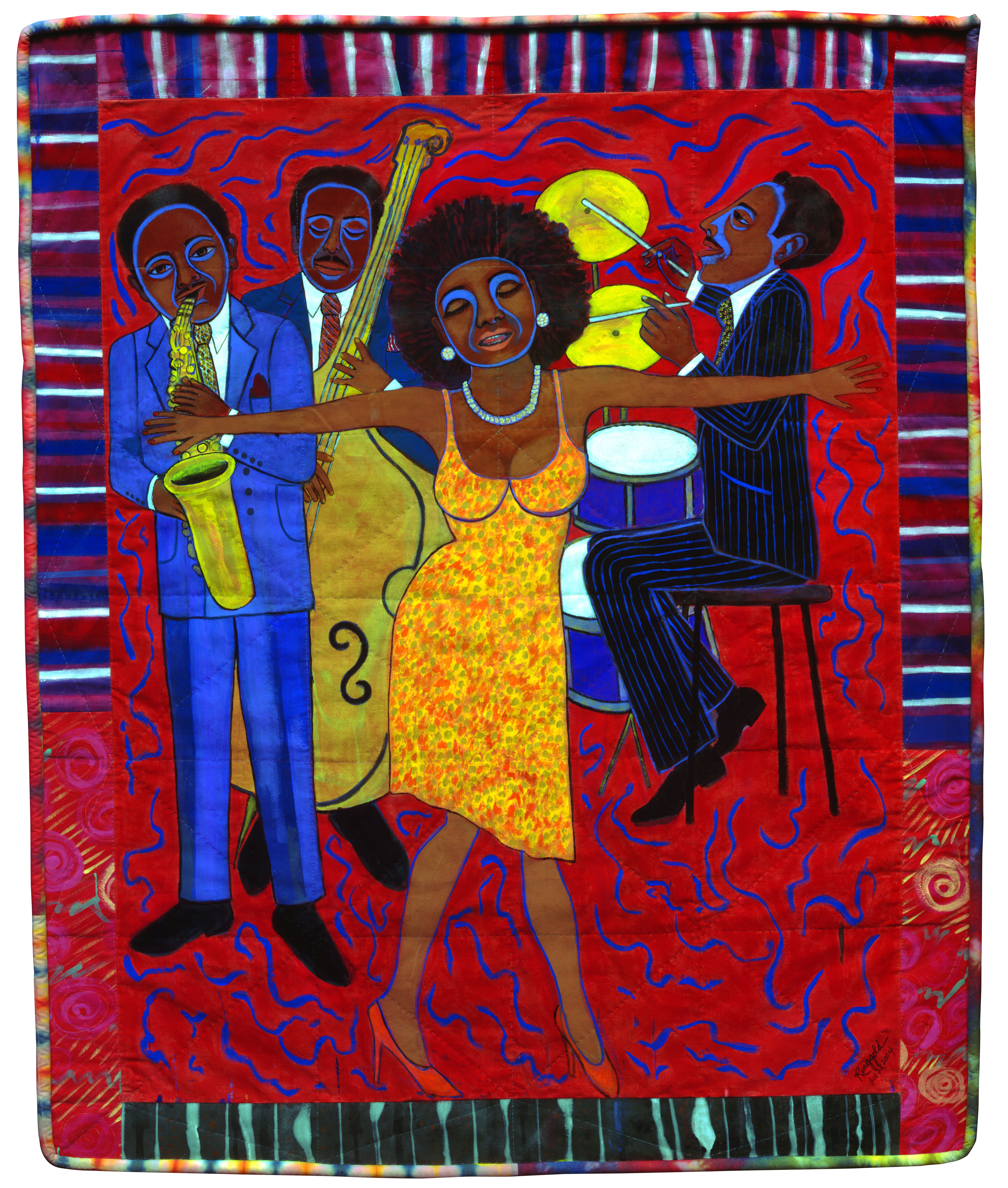

Faith Ringgold, Jazz Stories: Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #1: Somebody Stole My Broken Heart, 2004.

©2018 FAITH RINGGOLD/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY ACA GALLERIES, NEW YORK

During the 1960s and ’70s, Faith Ringgold was at the center of a community of black female artists dealing in their work with issues related to race, gender, and their intersections. While her “story quilts”—woven pieces that reveal aspects of her autobiography—are well-known, her paintings and sculptural works have only recently received mainstream recognition. With a retrospective of the artist’s work now on view at the Serpentine Gallery in London, we went through our archives and pulled out excerpts from interviews with Ringgold and reviews of her work, including musings on her first-ever solo exhibition, at Spectrum Gallery in New York. American People Series #20: Die (1967), the 12-foot-long painting mentioned in that review, was recently acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York—a sign of Ringgold’s rising star. —Alex Greenberger

January 1968

Faith Ringgold [at Spectrum Gallery in New York] paints big bold protests against the Black-White situation. Die is a horror cartoon of bloody street fighting with two terrified children (colored and white) huddled in each other’s arms. The Flag Is Bleeding shows a blond girl arm-in-arm with a knife-clutching Negro and an unarmed white man—all overlaid with a flag that bleeds. Formally, Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power is the best: rows of eyes and noses of many shades with various legends worked into and over them.

—“Reviews and previews,” by Ralph Pomeroy

Faith Ringgold, American People #15: Hide Little Children, 1966, oil on canvas.

©2018 FAITH RINGGOLD AND ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY PIPPY HOULDSWORTH GALLERY, LONDON/PRIVATE COLLECTION

October 1980

Faith Ringgold, 45, with mordant satire, grotesque distortions and a use of light based on “the blacks and browns and grays that cover my skin and hair,” has expressed the double bind of being black and female in America. Because of her strong feminist stance, she was attacked by black men who felt that her allegiance to black activism (her first major paintings portrayed the civil rights struggles of the early 1960s) should supersede her support of the women’s movement. And within Ringgold’s own family, politics took a personal toll. Her daughter Michele Wallace wrote in her controversial book, Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, that her mother stood in the way of her development as a feminist. Ringgold maintains that Wallace’s view was a fiction designed to provoke comment and sell the book. “Everyone wanted a black feminist book and no one cared where it was coming from. And the media love anything that’s anti-mommy.”

In the late 1960s, during a period of incorporating African designs and motifs into her canvases, Ringgold found that she had to give up painting because it was isolating her from her family and friends. “No one in my family understood why I had to be alone undisturbed for such long periods of time,” she says. “So I went to soft sculpture because I didn’t have to close the world out. Artists need support and sometimes you must retrench to get some.” Ringgold turned to wall hangings and soft dolls that satisfied a tactile and spiritual need to work in textiles and create tapestries, masks and puppets similar to the objects women in primitive societies traditionally made. These three-dimensional portraits of black women, sympathetic, humorous and frank, are both individual stories and distillations of larger ethnic narratives.

—“A Decade of Progress, But Could a Female Chardin Make a Living?,” by Avis Berman

April 1987

You had to be there [at a Ringgold show at Bernice Steinbaum gallery in New York]; no mere description can do justice to Ringgold’s story quilts—works of art with the impact of folk tales or family stories. Illustrated narratives in paint and tie-dyed fabric, the quilts are brilliantly colored and strictly patterned. The work alludes to African art and to many other sources, including ’70s-style feminist art. While she uses stitchery and cloth, she avoids the condescension and the handed-down look that often accompany feminist art using traditionally feminine means. Her work is so strong, so original, that her borrowings become outright thefts; everything she takes becomes hers. . . .

Figuring prominently in Ringgold’s curriculum vitae, available at the gallery, are the comings and goings, accomplishments and interests of her two daughters, her mother and other family members, which suggests that her own life as an individual, even as an artist, is not separate from her life in a community. This identification with her community allows her to make statements about such broad subjects as black American life or feminist politics without losing her compelling, singular vision.

—“New York Reviews,” by Margaret Moorman

Faith Ringgold, The Flag is Bleeding #2 (American Collection #6), 1997.

©2018 FAITH RINGGOLD/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY PIPPY HOULDSWORTH GALLERY, LONDON/PRIVATE COLLECTION

June 1999

Ringgold’s first “story quilt” grew out of her frustrated attempts to publish her autobiography. “I figured, I can’t get anything published, so I might as well write my story with my art,” she once told a reporter.

That first “story quilt,” Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima, unabashedly advertises itself in its text as “Quilt and Book by Faith Ringgold.” In colloquial dialogue, she tells the story of Jemima Blakely, who inherits the fortune of her New Orleans employers, moves her family to Harlem, opens a restaurant, and finally dies in a car accident back home in Louisiana. “I felt she was my first feminist issue,” Ringgold has said. Visually, the piece has more in common with the kind of quilts her slave great-great-grandmothers made than with her “French Collection” paintings: craft elements such as embroidery and beading adorn the rather static head-on portraits of the various actors in her Jemima drama. Today’s pictures are more painterly and visually complex; they can be experienced independent of their texts, unlike Jemima.

—“The Ringgold Cycle,” by Gail Gregg

Spring 2016

Ringgold’s quilts have never quite been taken seriously by most major museums, perhaps because of their craft associations, whimsical range of subjects, or faux naive painting style. Neither the Museum of Modern Art nor the Whitney Museum owns one—though the latter has a 1971 collage calling for the release of Angela Davis. The Guggenheim has owned her masterpiece Tar Beach since the year it was made, 1988, but has never put it on view in New York.

That said, last fall the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, snapped up one at auction for a cool $461,000, a new record for Ringgold for a public sale by a multiple of 30. It dates to 1989 and was commissioned by Oprah Winfrey as a gift to Maya Angelou for Angelou’s 61st birthday. “One of the things that is extraordinary about [Ringgold’s] quilts in general, but this one in particular, is that it has these layers that intersect with each other,” said Margaret C. Conrads, the museum’s director of curatorial affairs. “There’s painting, quilt making, text—there’s high art, craft, figuration, abstraction, the visual aspects, narrative storytelling.”

—“The Storyteller,” by Andrew Russeth

[ad_2]

Source link