[ad_1]

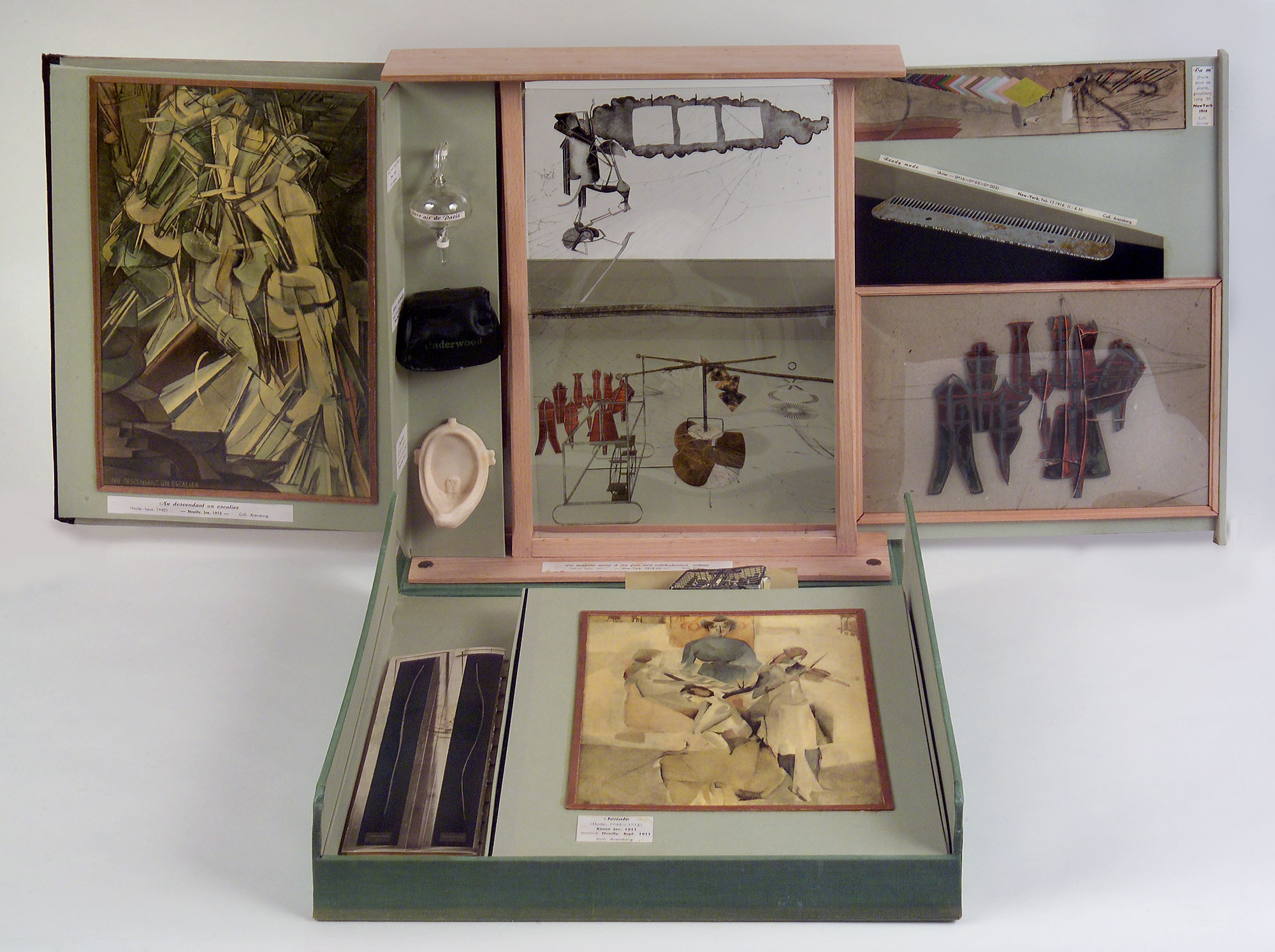

Marcel Duchamp, assembled by Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, Boîte-Series D, 1961.

©2019 MARCEL DUCHAMP/ADAGP, PARIS/SOMAAP, MEXICO/COLLECTION OF FRANCES BEATTY AND ALLEN ADLER

It has been a big month for Jeff Koons. One of his most famous pieces, Rabbit (1987), sold for $91.4 million at Christie’s in New York, allowing him to reclaim his status as the most expensive living artist, and shortly after, New York Times co-chief art critic Roberta Smith defended the often-reviled figure in an essay titled “Stop Hating Jeff Koons.” Meanwhile, a major show featuring the artist opened in Mexico City at the Museo Jumex: “Appearance Stripped Bare: Desire and the Object in the Works of Marcel Duchamp and Jeff Koons, Even.” Running through September 29, it’s a 70-work blockbuster that looks at how those two giants of 20th-century art history were affected by—and helped shape—commodity culture. In advance of the exhibition, ARTnews sat down with the show’s curator, Massimiliano Gioni, to discuss the affair. Over coffee in the lobby of the New Museum in New York, where Gioni is artistic director, the show’s curator chatted about, among other things, Koons’s cynicism and why Duchamp was a sellout.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

ARTnews: You just completed installation of the show at Museo Jumex. How do you think it’s turned out?

Massimiliano Gioni: I’m usually very pessimistic about my shows, so I don’t know if this is a good thing or a bad thing, but seeing it in the space, it seems to make sense. [Laughs.]

How did the show come together?

I’ve known the work of Jeff Koons for a long time, and I met him for the first time when I curated his work in a group show in the early 2000s. I was working on another text about his art in which I’d been thinking of Duchamp in relation to his work—it’s obviously a very strong presence. A couple years ago, Jumex asked me if I wanted to do a Koons show, so I doubled down. I said, “Why don’t we do a Duchamp/Koons show?” I proposed it to them, they liked the idea, and then I proposed it to Jeff, and he liked the idea. Also, there is a Mexican connection to Duchamp because of Octavio Paz, who wrote two very important essays about Duchamp, one of them being “Appearance Stripped Bare,” the title of which I borrowed for the show.

Jeff Koons, New Hoover Convertibles, New Shelton Wet/Drys 5 Gallon, Doubledecker, 1981–87.

©JEFF KOONS/ASTRUP FEARNLEY COLLECTION, OSLO

You mention in the catalogue that the concept of the shop window formed one of the bases of the show. What was so formative about that?

Helen [Molesworth] wrote this beautiful essay called “Rrose Sélavy Goes Shopping,” about a note that Duchamp wrote in 1913. In this note, which is very cryptic and oracular, he talks about the question of shop windows that hide the coitus behind a sheet of glass. He goes off on a digression about how the shop window amplifies desire and what happens when that desire is consummated. Paradoxically, that consummation is actually a frustration of desire, because by fulfilling that desire, the sexual tension is destroyed. For me, Helen’s essay on that note opened up a whole new reading of Duchamp.

You told me you’re not a fan of what you’ve called the “mystical” or “alchemical” readings of Duchamp, which place an emphasis on spirituality and his readymades, and you didn’t deal much with the wordplay and irony typically written about with respect to both artists’ works. Tell me about your theoretical approach to the show.

I looked more at Duchamp in the sense of commodities, at Duchamp as visualizing, at the beginning of the 20th century, the explosion of capitalism in cities. It’s very much about how our existence changes in cities when they become spaces of commerce. With Koons, you have that taken to the most immaterial form—entertainment. The city of Duchamp is the city of commerce. The city of Koons is the city of entertainment.

Koons viewed 1980s New York with a certain cynicism symptomatic of that era. With “The New,” a series of sculptures in which vacuums are placed above Dan Flavin–like fluorescent lights, he poked fun at shop displays and Minimalism, and showed how art and commerce were one in the same. In his “Art Ads,” he placed photographs of himself in magazines in the form of advertisements, effectively turning himself into a commodity. Do you think of Duchamp’s work as being cynical in the same way?

That’s a good question. The Duchamp lover will say he is pure and Koons is compromised. Duchamp’s position was that he was just a guy making a living by selling Brancusi sculptures. [Laughs.] You could say he was a courtesan to rich collectors, just as much as people accuse Koons of being that. Duchamp was very friendly with collectors, probably more so than Koons himself!

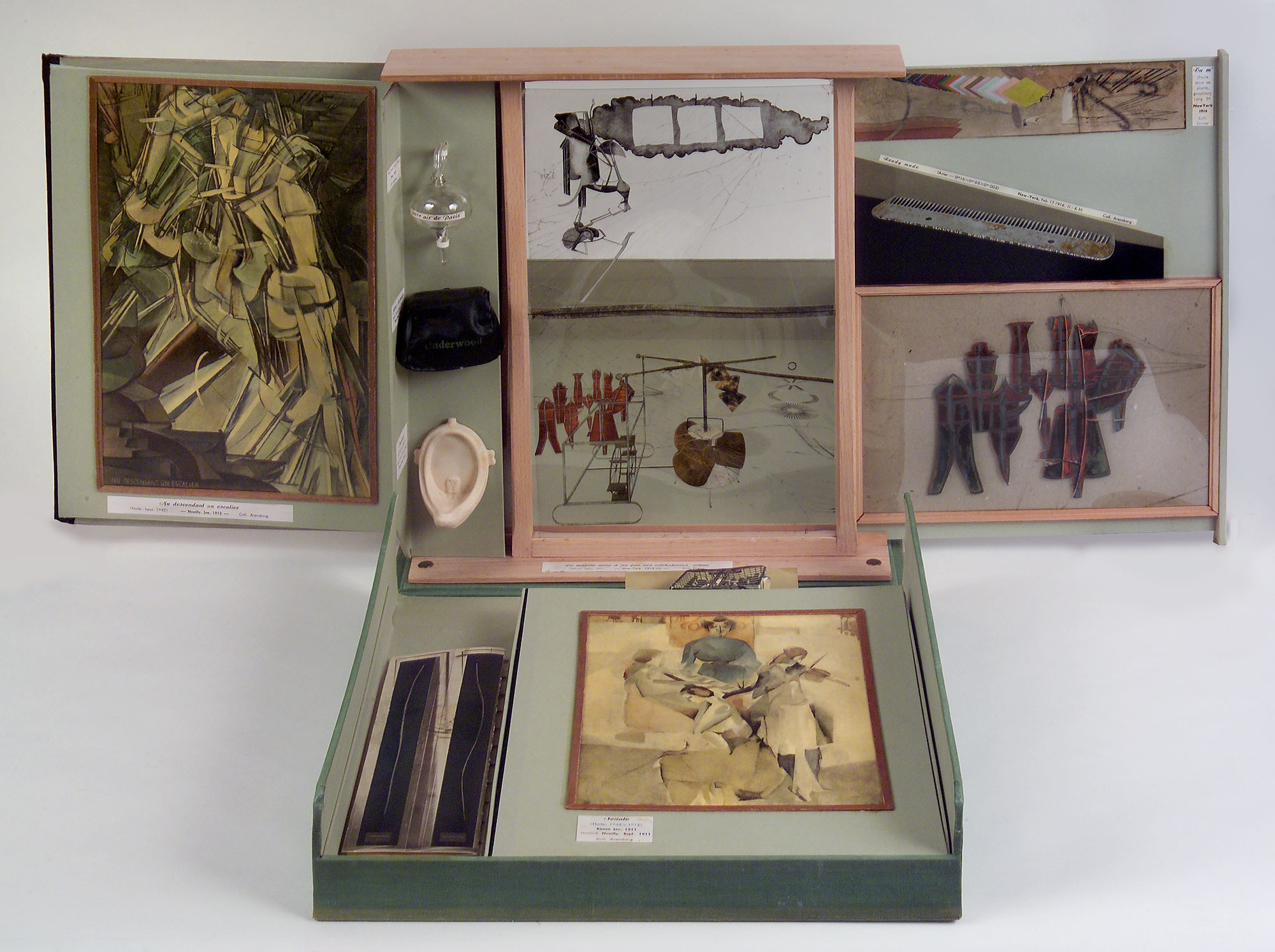

Marcel Duchamp (in collaboration with Man Ray), Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath, Veil Water), 1921.

©2019 MARCEL DUCHAMP/ADAGP, PARIS/SOMAAP, MEXICO/COURTESY SOTHEBY’S, INC./THE BLUFF COLLECTION

So Duchamp really aimed to ingratiate within the art market, then.

I mean, Monte Carlo Bond [a 1924 piece that took the form of financial instruments that Duchamp sold to fund his roulette-gambling method] revealed the artist as a kind of sellout, in ways not too dissimilar from the “Art Ads” by Koons. He wasn’t outside the system. He was a consultant, if you will. The interesting thing—which is also true of Koons, to an extent—is that Duchamp created a system in which all those gestures seem performative. Both of them are complicating notions of sincerity and performance. Some might say one more effectively than the other. One appears to be so sincere that you think he must be joking! [Laughs.]

And then the other appears to be joking so often, he must be sincere.

Yes, exactly. Both definitely exist in such a way that their work cannot be taken at face value.

The critical reception of Koons and Duchamp couldn’t be more different today. Duchamp is perceived, almost universally, as being one of the very best and most influential artists, whereas Koons is often considered art-market fodder. You could even say his work has started to seem banal—a line of thinking prefigured by his own 1988 series “Banality,” sculptures that appropriate and reconfigure the form of “non-artistic” objects, such as figurines and tchotchkes of the sort that you’d find at gift shops. Does your exhibition aim to lend a certain gravitas to Koons’s work that’s typically absent?

It’s not a show about establishing Koons’s authority based on Duchamp. I hope the show looks at two artists who are bookends of the 20th century, who have both tried to understand what was happening to objects and to us in two different moments of the history of production and consumption.

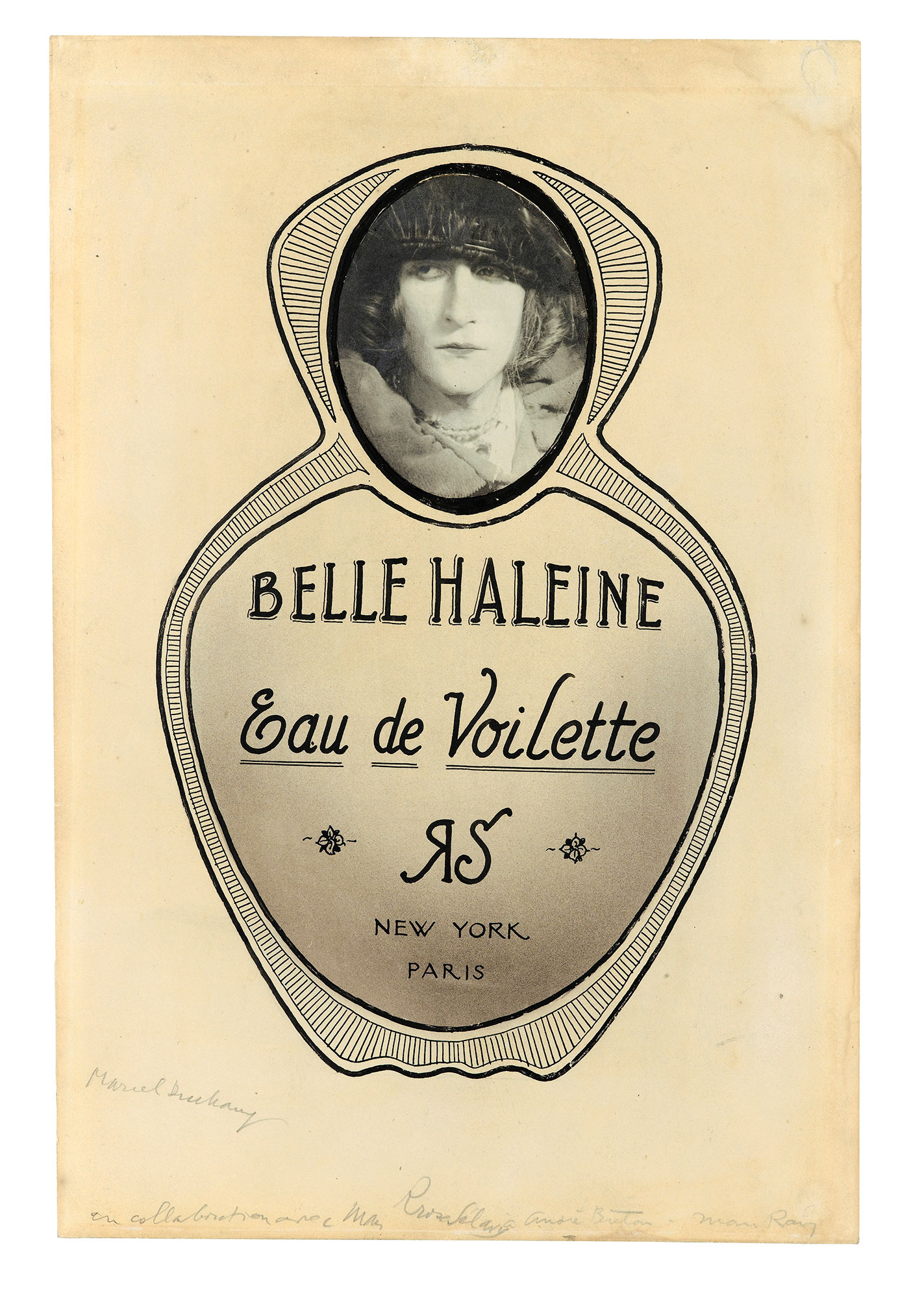

Jeff Koons, The New Jeff Koons, 1980.

©JEFF KOONS/PHOTO: DOUGLAS M. PARKER STUDIOS, LOS ANGELES/PRIVATE COLECTION

I’ve never thought of Duchamp and Koons much with respect to identity, but that’s an aspect touched on often in the catalogue essays. Class and taste are your main concerns, you write in your introduction.

The question of identity is crucial within the exhibition. The show presents the individual as compromised [by] the market, by capital, by desires for success, and in doing so, Duchamp and Koons present a much more complex notion of who we are and how we are implicated in the world around us. I think a show also needs polemical angles, and one of the polemical positions here is to look at Koons beyond the image that he’s now being forced into, which is as an artist of the super-rich. I’m not denying that’s where the product is sold, but I also look at how his work has problematized notions of class and taste, in a way that had been dismissed through a certain interpretation of his work.

But you can’t deny that certain bodies of work by Koons have fed this reception of him as the archetypal heterosexual white male artist. Perhaps the most notable series in this respect is “Made in Heaven,” the sexually graphic paintings and sculptures of Koons fornicating with his then-wife. Some works from it are included in the Jumex show.

If we want to discuss sexual politics, I think it’s a bit more complicated than straight white male aggressive behavior. Of course, there are multiple points on it. I see it as a kind of parable of invention. It is more about the self and gender as performance than as essentialism, whiteness, heterosexuality, masculinity. Again, the show is meant neither to establish a lineage nor to defend Koons, but I think it’s important also to be aware that reception is partial, as it is for many artists. At the same time, I’m aware of the polemical aspect. For a while, I was joking that the show could be called “The Devil and the Holy Water,” an Italian expression that means you have two opposites together. It would be up to you decide who is the devil and who is the holy water! [Laughs.]

Jeff Koons, Grotto, 2000.

©JEFF KOONS/PHOTO: DAVID HEALD, ELLEN LABENSKI/COURTESY GAGOSIAN

Photography is clearly important to the “Made in Heaven” work, as well as to many others included in “Appearances Stripped Bare.” You’ve included images of Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy, his female alter ego, and you have Warhol’s screen test of him. You also have works from Koons’s “Art Ads” series. Was photography something you had in mind while putting together the exhibition?

It’s an interesting point. I didn’t really address it, technically. If you wanted to, though, you could write an entire essay about how many of Koons’s sculptures are born photographically, from “Banality” on.

That’s true—many of his big “Balloon Dog” sculptures, for example, are modeled using computer imaging these days.

Yeah, now it’s pure data. That’s also an interesting subtext within the show—not only the transformation from an economy of production to an economy of consumption, but also from the transformation of a commodity from a thing to data.

[ad_2]

Source link