[ad_1]

Eliza Douglas in rehearsal for Anne Imhof, Sex, 2019.

NADINE FRACZOWSKI/COURTESY GALERIE BUCHHOLZ, BERLIN, COLOGNE, AND NEW YORK

To enter a performance by Anne Imhof is to part ways with traditional logic about the boundary between viewers and artworks. You might get knocked over by a dancer. You might lose the ability to leave when you want, because you may get cornered into tight spaces by other viewers’ bodies. You might catch performers gazing back at you, to the point of discomfort. I witnessed or experienced all of this during the German artist’s latest project, Sex, a tour de force now on view at the Art Institute of Chicago that is as mesmerizing as it is arduous.

Imhof favors single-word titles. Sex follows Angst (2016) and Faust (2017), the latter of which won her the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale the year it premiered. (Her award is displayed in Sex, placed on the floor as an impish perch for a can of Modelo Negra beer.) Sex’s name conjures a multitude of meanings, and the work itself is imbued with an ambiguity that seeps into every image and prop on display.

Enacted by a troupe of young dancers who also sing, text, and vape, Sex recently shook up London crowds when it had a weeklong run at Tate Modern in March. Yesterday afternoon, the work debuted stateside at the Art Institute (its only U.S. host), where it remains through July 7. (Afterward, it will also be staged at the Castello di Rivoli in Turin, Italy.)

For the vast majority of its run, Sex will appear as a static installation, composed of paintings and objects made by Imhof and her core collaborator, her partner Eliza Douglas: yellow and black aluminum works meant to invoke sunsets, mattresses littered with broken phones and lighters and cutesy bongs, large-scale, Warholian silkscreen prints of Douglas caught in a silent scream.

But the four-hour-long performances, occurring once per day through Saturday, are really what you want to see—if you can get in. Only 100 people are allowed in at a time, and most visitors linger. Arriving one hour after doors opened yesterday, a friend texted me from the galleries beyond, saying, “I feel like I’m waiting in line for Berghain lol.”

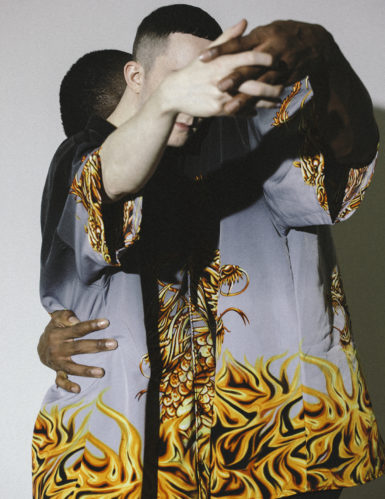

Mickey Mahar and Josh Johnson in rehearsal for Anne Imhof, Sex, 2019.

NADINE FRACZOWSKI/COURTESY GALERIE BUCHHOLZ, BERLIN, COLOGNE, AND NEW YORK

Indeed, while inside, it is also difficult not to think of pretentious nightclubs in Berlin. The only lights are blinding strobes that flash aggressively. The music, which veers from minimal techno to metal to near-medieval, is often thunderous. Smoke from a fog machine mingles with exhaled puffs from vapes that smell like cotton candy. The performers, dressed in athleisure garb, are moody and hot—cooler-than-thou types. They contort their bodies to create vivid, oneiric images. A couple half-wrestles, half-waltzes in a strange, tender embrace. A performer spins, like a sycamore seed in slow motion, to a hair-raising tune. Another, seated on an elevated white bed, slowly empties a box of sugar.

The gallery they occupy is long and narrow, dominated and divided by a towering structure built to resemble a pier that faces floor-to-ceiling windows. Bottles of Modelo and wilting flowers lie by the pillars. The platform takes the form of a metal catwalk on which the performers at times crawl or perch, their long legs dangling above our heads.

“I thought of boats,” Imhof told ARTnews, when asked about her chosen architectural form. “The pier is a place where you are neither here nor there—the in-between territory.”

It is, in other words, the perfect metaphor for what feels like our current, collective state of feeling unmoored. Sex is not so much about erotic action as it is about feelings of alienation, intimacy, and aggression. The performers often mope, but they also spring from stillness into sudden sprints, mosh violently, push against walls, and slap themselves. Sometimes they check their phones—Imhof, following at a distance, is texting them directions. Scattered props like beer cans and motorcycle helmets help set the chaotic scene, the detritus of capitalist America à la Cady Noland. And for the millennial generation: a pyre of graphic T-shirts that Hot Topic probably once sold, plus neat rows of La Croix cans (Imhof’s crew apparently favors mango).

Sacha Euseube in rehearsal for Anne Imhof, Sex, 2019.

NADINE FRACZOWSKI/COURTESY GALERIE BUCHHOLZ, BERLIN, COLOGNE, AND NEW YORK

“There is an element in her work that resonates so strongly with how we experience the world today,” Hendrik Folkerts, the Art Institute’s curator of modern and contemporary art, said. “It is so full of angst and a certain anxiety—whether that is infused by ecological and psychological concerns.”

The white cube of the Art Institute’s gallery is radically different from Tate’s basement, where Sex spilled over three gritty industrial spaces. Imhof had to revisit and reconfigure the choreography and sound in Chicago, Folkerts said. “Now all these layers are concentrated almost on top of each other in one space.”

Often, being in the audience feels just like that, too. There is no one optimal viewpoint to observe this protracted sequence of unfolding images—which is partially why Sex feels so exciting. During Sex, viewers are always in the way of someone else. I became terribly aware of my own body, and I very quickly realized I was dehydrated. In fact, at the end of four hours—which felt much shorter than that—I was positively drained. This morning, I woke up feeling weak and achy from the previous day’s performance. It felt like a workout.

But, for all the pain and masochism that the performance entails, I left Sex thinking of how Imhof balances darkness with light. There was a moment when a vocalist delivers a melancholic rendition of the American folk song “O Death,” for example, but it was counterbalanced by points that transport viewers to some spiritual place, like when performers stand in light streaming through windows while the songs of a heavenly chorus play via speakers. Perhaps Imhof is nudging us zombies to picture the view from above—to try to imagine standing on her abstracted pier, gazing toward a distant, maybe brighter, horizon.

[ad_2]

Source link