[ad_1]

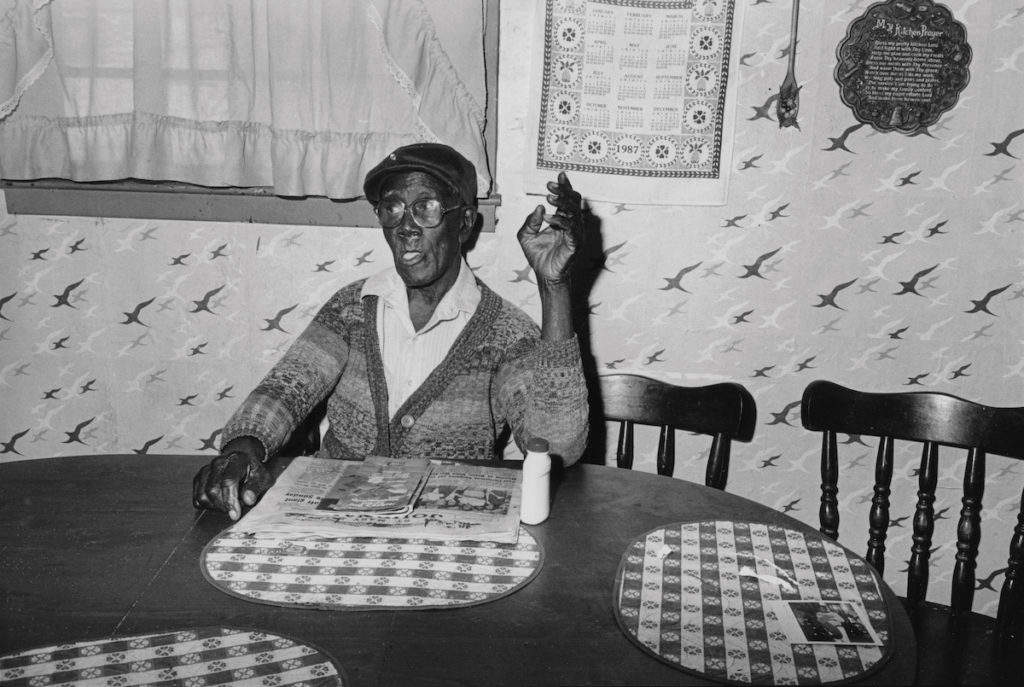

Guy Mendes, Royal Robertson’s House (Baldwin, LA), 1986.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND INSTITUTE 193

Between around 1984 and 1991, poet and publisher Jonathan Williams—usually in the company of one or the other of his photographer friends Guy Mendes and Roger Manley—made a series of road trips through the American South, tracking down and visiting with self-taught artists in Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina. (They left Florida strictly alone; it gave Williams, in his words, the willies.)

Many of these artists were working in the African-American artistic tradition of the yard show, a type of outdoor art environment that proliferated in the South after the civil rights movement. Several of them, including Thornton Dial, David Butler, and Sister Gertrude Morgan, had been featured in Jane Livingston and John Beardsley’s landmark 1982 exhibition, “Black Folk Art in America (1930–1980),” at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. Most, at that time, were still living, their words, works, and environs captured in the moment by the authors.

Williams shelved his rambunctious account of those trips in 1992. Institute 193 recently published the book, titled Walks to the Paradise Garden: A Lowdown Southern Odyssey, in conjunction with the now-closed exhibition “Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads” at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Edited by 193’s founder, Phillip March Jones, and illustrated with Mendes and Manley’s photographs, it’s a valuable—if unorthodox—addition to the history of self-taught art.

A writer associated with Black Mountain College, Williams, who died in 2008, is best known for cofounding the Jargon Society, an imprint dedicated to publishing the work of under-known writers, photographers, and artists. He was a connoisseur of found language, and along with his profiles of more than 80 artists—plus a fair number of just plain eccentrics—the book offers collections of town names (“Map of Kentucky and Its Litany of Glorifications” includes the hamlets of Red Hot, Arminta Ward’s Bottom, Thousandstrikes, Bagdad, Bee, Moon, Boring, and Byproduct, as well as Hi Hat, Sugartit, Pride, Pippa Passes, Sacred Wind, Dingus, Rowdy, and Decay) and text from signs on bait shops (“Spring lizards polish sausage”), convenience stores (“Ice pop ammo”), and in yards (“Television is a tunnel of lightning from hell”).

Williams’s own text is not for everyone. He digresses (one chapter is devoted to the joys of barbecue), hyperbolizes (artists are variously compared—in some cases not without reason—to Jasper Johns, Paul Klee, and Pieter Bruegel, among others), and fulminates (while visiting artist Sam Doyle on St. Helena Island in South Carolina, Manley and Williams go out to eat on nearby Fripp Island: “One of those amazing wasp-a-rama enclaves [sentries and guard-houses, a restaurant featuring turf-and-surf specialties for the gratification of fat Republicans with loathsome children in Polynesian swimwear]. Don’t go, etc. I am making none of this up.”)

Guy Mendes, David Butler (Morgan City, LA), 1986.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND INSTITUTE 193

He is also opinionated, snobbish, and joyously incorrect. Some may find his prose too soaked in the cadences and vocabulary of the region for their taste. But he’s a sharp-eyed observer of Southern culture and its contradictions—this book is as much about the South as it is about art—and his deep admiration for the artists in the book is obvious. Here he is describing Raymond Coins, a sculptor from Stokes County, North Carolina: “He is a member of the Primitive Baptist Church. A strict and severe personality, and, despite all, an extraordinary artist. Talking to him, I found myself thinking: a mule would know as much about art as this suspicious old codger. No matter. He makes profound, iconic figures that would bemuse the skin off a snake.”

Mendes and Manley, who shared Williams’s fervor for vernacular and self-taught art, emerge through their black-and-white and color photographs as artists in their own right. Mendes’s portrait of Butler at his kitchen table, for example, is an extraordinary image; depicting a figure in a field of boldly patterned, interlocking shapes, it echoes Butler’s own cut-tin paintings. Manley’s pictures of Dial, elegant and at ease in his studio doorway, and artist JB Murry, holding a bottle of sacred water through which to view his drawings, vividly convey both men’s assurance in themselves and their vision.

Not one of the three ever presumed to compare their lot with those of the people they befriended (“Try saying ‘Have a nice day!’ to a person who has had few nice days in her whole life,” Williams writes in a chapter on the ceramist Georgia Blizzard. “How insolent you would feel. Imagine making art of great spiritual force when you have almost no money and have to take care of a bedridden older sister and a daughter in a house with no privacy at all.”) But each in his way was something of an outlier himself, if only by virtue of being a regional artist.

An Ashville native and a resident of New York and San Francisco in the 1950s, Williams chose to lead, for the last 40 years of his life, a rural existence in North Carolina with his partner, Tom Meyer. Born in New Orleans, Mendes was long a member of the Lexington Camera Club—a group that also included the photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Originally from San Antonio, Manley is the director of UNC Raleigh’s Gregg Museum of Art & Design.

Guy Mendes, Mary T. Smith’s Yard (Hazelhurst, MS), 1986.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND INSTITUTE 193

Some of the artists in the book had achieved a degree of fame by the time the authors met them. The work of Reverend Howard Finster—after whose Paradise Garden public park in Pennville, Georgia, this book is titled—had already appeared in a 1983 R.E.M. music video and on a 1985 Talking Heads album cover. Others, like Mirell Lainhart, whose art was limited to polka-dotting every surface in his house in Jackson County, Kentucky, with black spray-paint, will remain forever obscure.

And while a few of the environments documented here have been preserved, including Paradise Garden and Pasaquan, the compound built by Eddie Owens Martin (aka St. EOM, former New York City rent boy and founder of his own religion), many others had already vanished, like Jolly Joshua Samuel’s “Can City” in Walterboro, South Carolina, wiped out by a tornado, and Mary T. Smith’s yard show of paintings on tin in Hazlehurst, Mississippi, bought up on the cheap by collectors. (Smith, one of the artists in the 1982 Corcoran exhibition and an influence on Jean-Michel Basquiat, died penniless.)

In addition to artists, we meet fabulists like Edwin H. Paget of Raleigh, North Carolina (who has “History’s most significant man” printed on his calling card); legends like “Cowboy Steve” Taylor, owner and operator of radio station WSEV in Lexington (“This old, rheumatic black man was one of the best Country and Western DJs anywhere around”); and characters like Lexington drag queen Bradley Harrison Picklesimer (“half-Marilyn Monroe and half-de Kooning woman”). This last category also includes members of the Lexington creative community: in one photograph by Mendes, Meatyard semaphores with a Stetson hat from outside the screen door of a deserted house; in another, Kentucky novelist Ed McClanahan cuts an outré figure in bellbottoms, aviator shades, and fuzzy chapeau.

One chapter is devoted to a hair-raising road trip with the controversial collector (and terrible driver) William Arnett, who in the late 1970s decided that the best of the African-American vernacular artists in the South were as worthy of attention as any artists in history and, as Williams writes, “put his money where his mouth was.” Another recounts the sad history of the rather creepy “doll babies” made by Martha Nelson of Mayfield, Kentucky; they inspired the Cabbage Patch Kids and were licensed by Xavier Roberts without Nelson’s permission.

Much of the time, artists are represented in their own words. Murray was too old and ill to talk about his work, but Williams digs up a transcript of an earlier recording of him to accompany Manley’s picture. (“I wasn’t crazy,” Murray says, “I feel like the Lord was with me.”) Edgar Tolsen speaks of a recurring dream in which his carved figures come to life and surround him, saying, “You made me, you made me!” (“I can’t never figure out what they want me to do about it,” he tells Guy.) In one of the book’s last chapters, Dial, a master at combining political content with formal accomplishment in his art, explains his new painting, If You Want to Do Anything or Buy Anything or Kill Anything in the United States, You Got to Have a License (1988).

“[W]e’re talking about a South that is both celestial and chthonian,” Williams says in his introduction. Writing at a watershed moment in the mainstream acceptance of outsider art, he appears to have found in voices like Dial’s an antidote to all he felt was repugnant about the South and about America. They still seem so today.

[ad_2]

Source link