[ad_1]

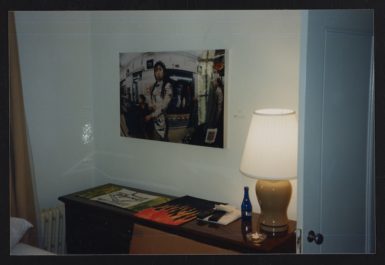

Taking in the scene at the 1994 Gramercy International Art Fair in New York.

COLIN DE LAND COLLECTION, 1968–2008/ARCHIVES OF AMERICAN ART, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

It’s been difficult lately to find any significant stretch of the year without stops on the art-fair circuit, as the events continue to pop up, fully formed and slick with snake oil, in convention centers around the world, one often indistinguishable from the next. But as another week of art fairs runs in New York, it’s heartening to be reminded of alternatives to the prevailing model, and the fact that, over the past three decades, a striking number of ad-hoc showrooms have cropped up in what might seem unlikely sites: hotel guest rooms.

Perhaps the most famous example of this model came in 1994, when New York dealers Pat Hearn, Colin de Land, Matthew Marks, and Paul Morris banded together to start a fair in response to the seemingly imminent folding of Hearn’s beloved but financially struggling gallery.

A Mariko Mori work on view at the Gramercy International Art Fair.

COLIN DE LAND COLLECTION, 1968–2008/ARCHIVES OF AMERICAN ART, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Marks told me in an email that Hearn “was just back from Europe and had visited an art fair in a hotel that she thought was pretty interesting.” (Marks and Morris remember the fair as potentially taking place in Cologne, which would suggest Hearn was referencing Unfair, dealer Christian Nagel’s early ’90s rejoinder to the perceived exclusivity of the city’s venerated Art Cologne fair.) Marks continued, “Business was lousy in those days and all the young dealers were struggling. [Hearn] wanted to know what I thought about doing something similar in New York. . . . Eventually they found a sympathetic manager at the Gramercy, which we all thought was perfect. We reserved the rooms, called our dealer friends to join us, stayed up all night addressing invitations, and crossed our fingers that someone would show up.”

And thus the Gramercy International Art Fair was born, with around 40 dealers taking up residence across several floors of the hotel, which was by then 70 years old and had seen better days. (This was well before hotelier Ian Schrager acquired it in the early 2000s and gave it a full renovation, overseen by Julian Schnabel.)

The fair was an immediate success. “We were totally unprepared for the crowds that came,” Marks said. “The lobby was packed all weekend. The elevators couldn’t handle the capacity and people were walking up ten flights to get to our rooms.” In lieu of booths, dealers were allotted rooms where artists could stage interventions as they desired. Mark Dion, for instance, sold $2 glasses of lemonade (with or without vodka) from a makeshift stand that included informational materials about his work.

A Barkev Gulesserian sculpture in Canada’s bathroom at the Dependent in New York in 2011.

ANDREW RUSSETH/16 MILES OF STRING

Lisa Spellman, the owner of 303 Gallery, said, “Karen Kilimnik’s piece was in the bathroom: red paint dripping down the sink and walls reading, ‘Political piggies must die.’ Rirkrit Tiravanija was serving tea from his set, a sound piece by Kristin Oppenheim was playing, and we had works by Collier Schorr, Hans-Peter Feldmann, and Sue Williams. Everyone was hanging out on the couch and the bed. I sold one piece, but it was so fun!”

What was once a scrappy upstart has since become one of New York’s primary fairs. In 1999, the Gramercy changed its name to the Armory Show, and in 2001 moved to piers on the West Side of Manhattan along the Hudson River. The 25th edition of the fair runs through this weekend, and its organizers are hosting a range of special programming to coincide with this anniversary, looking back at its history, which included fairs at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles in 1998 and the Raleigh Hotel in Miami in 1999.

Artist Rose Marcus said she was conscious of the Gramercy’s legacy when she organized her own alternative art fair, the Dependent—its cheeky name a riff on the Independent fair, which celebrates its 10th edition this year. The Dependent ran in 2011 and 2012, first in a Four Points by Sheraton and then a Comfort Inn on the Lower East Side. Both iterations of the Dependent featured between 30 and 40 galleries, from L.E.S. mainstays like Canada to further-flung outfits like the Greenpoint-based nonprofit Cleopatra’s.

A work by Andra Ursuta at the room of Ramiken Crucible at the 2011 Dependent fair in New York.

ANDREW RUSSETH/16 MILES OF STRING

“The Dependent Art Fair came about as a result of conversations between myself and other artists and curators who presented in the very first round of small booths dedicated to new projects at NADA Miami in 2010,” Marcus said. “I curated a booth of artists working adjacent to the traditional ‘gallery’ model”—including Real Fine Arts (the Brooklyn gallery, which shuttered in 2018, that launched the careers of Maggie Lee and Yuji Agematsu, among others) and DIS, the artist-run magazine cum curatorial platform cum streaming site.

Marcus continued, of that Miami presentation, “Ultimately, the projects served as a cumulative snapshot of interesting alternative models: People (on both the organizational and artistic sides) were really interested in developing new ways to show art within a boom or bust system and these spaces were operating at an incredibly high level. It felt like there was a lot of potential energy that clearly deserved its own organized fair.”

While hotels may not have the amenities of some big-budget conventional halls, at their best, they straddle the line between the hygge domestic realm and the aseptic white-walled booths typical of mainstream events, providing relief from fair fatigue that plagues dealers and collectors (to say nothing of writers), and lend a sense of intimacy to the experience of viewing (and hopefully buying) art.

Work by artist Al Freeman in the hotel room of 56 Henry at the Felix fair in Los Angeles last month.

ANDREW RUSSETH/ARTNEWS

And hotels also present a distinct practical advantage when hosting fairs. Gallery staffers often sleep in the same venue where works are shown, keeping costs down.

The model was recently revisited by the the Felix Art Fair, which Los Angeles collector Dean Valentine staged last month in his hometown at the historic Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, which was the first site of the Academy Awards, in 1929. Spread between the hotel’s 11th floor, penthouse, and “cabana level” (rooms surrounding the hotel’s expansive pool), Felix existed somewhere in between a conventional art fair (it helpfully included clear, professional signage designating booths and a map to orient visitors) and a hotel party.

Much like at the 1994 Gramercy, the crowds at Felix quickly surpassed the anticipated head count, and many visitors hoping to view the galleries up above were left stranded around the pool, where alcohol was imbibed with some enthusiasm. This scene, too, was reminiscent of its predecessor. Midway through the first Gramercy International, Marks said, he was concerned that the fair had worn out its welcome until Hearn exclaimed, “Guess what? The hotel bar had their best two days of business in over 75 years. . . . The manager loves us and already asked us when we are coming back!”

Hotel staffers are also perhaps uniquely suited to rolling with the punches of an art fair, being used to dealing with itinerant strangers. Remembering the 1994 event, Morris said, “They acted like it was just another day at the Gramercy.”

[ad_2]

Source link