[ad_1]

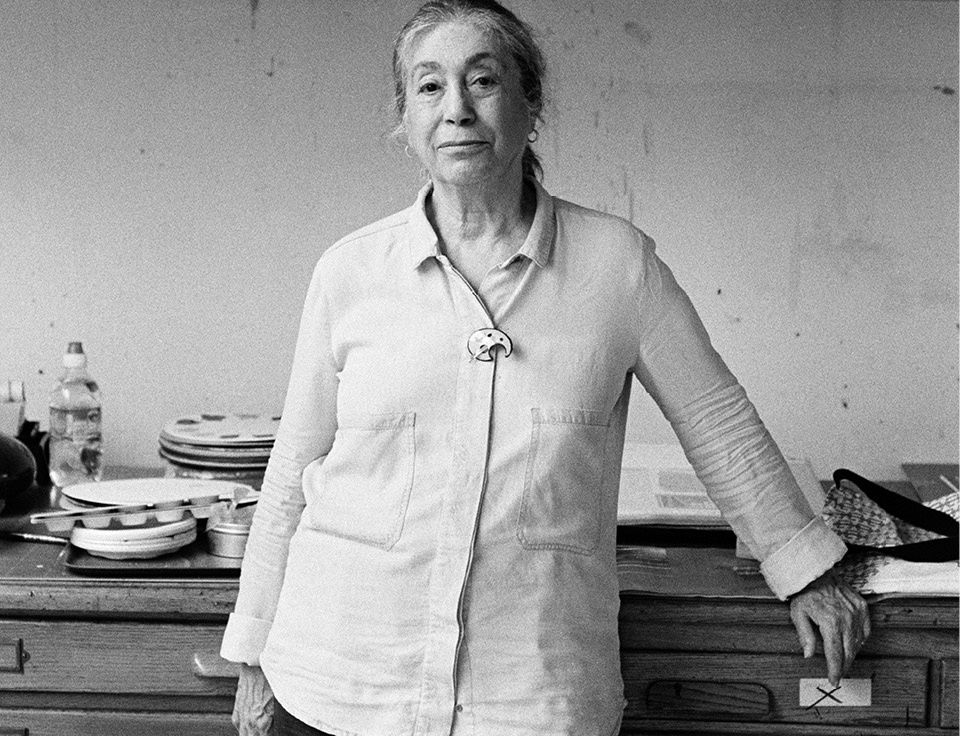

Susan Hiller.

©SUSAN HILLER/COURTESY THE ARITST/CARLA BOREL

Susan Hiller, whose mysterious, discomfiting, and alluring works attempt to commune with supernatural beings and make visible invisible forces, has died at age 78, according to Lisson Gallery, which represents the artist. A representative for the gallery said she died of a “short illness.”

“She was exacting, irreverent, mercurial, warmly mischievous, caring, and considerate,” Andreas Leventis, the gallery’s associate director, told ARTnews. “Expert on a diverse array of subjects, she wore her knowledge lightly and questioned everything.”

Hiller is often grouped loosely with the British Conceptualists of the 1960s and ’70s—she and Mary Kelly were the only two women included in a survey of the movement at Tate Britain in 2016. But Hiller eschewed the term “conceptual art,” saying she preferred the word “paraconceptual” to describe her practice, given her interest in the supernatural.

“I’m interested in occult powers, and if people find this ludicrous that is their problem,” Hiller told the Guardian in a 2015 interview. “I’m not a true believer but these things are there and to say they aren’t is ridiculous.”

Anne Gallagher, who curated a survey of Hiller’s work for Tate Britain in 2011, said in a statement, “Susan’s significance and influence as an artist is immense and will undoubtedly only increase over time, but her presence, her sharp intellect, her wisdom and her friendship will be much missed by so many.”

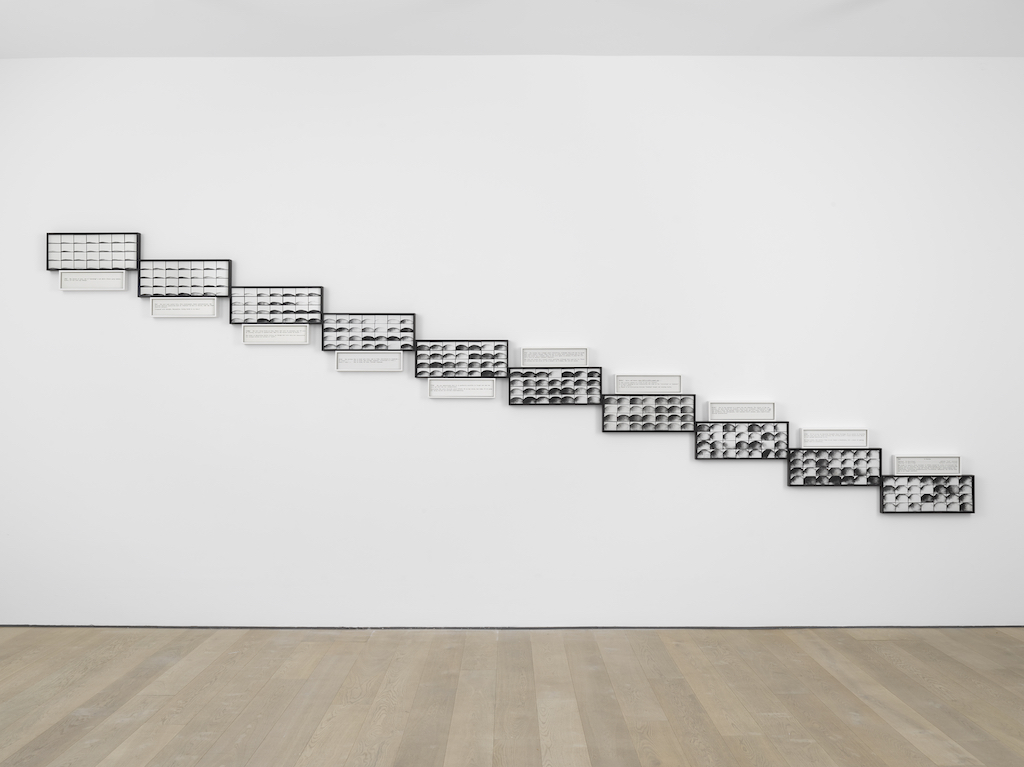

Susan Hiller, 10 Months, 1977–79, 10 black and white composite photographs, 10 texts, arranged sequentially.

©SUSAN HILLER/COURTESY LISSON GALLERY/GEORGE DARRELL

One of Hiller’s earliest and most memorable adventures with the paranormal came during the ’70s, when she began the project The Sisters of Menon (1972–79). Using a technique called automatic writing, in which a person scrawls text that is dictated by their subconscious or another person, Hiller penned words that she said were from multiple authors, whom she called the “sisters of Menon.” Scholars have related the project to methods relied upon by the Surrealists, Fluxus artists, and Conceptualists, and to feminist concerns from the era. When Hiller’s partner, David Coxhead, tried to speak with the sisters of Menon, they reportedly said they wouldn’t converse with men.

Throughout her five decades of work, Hiller often made use of appropriated materials, creating video installations and photo-based projects in which she, in a sense, shared authorship with a network of other makers. For Psi Girls (1999), Hiller lifted clips from a variety of movies, including Firestarter, The Fury, and Stalker, in which women are shown making use of telekinetic powers, moving glasses and pencils simply with their minds. Hiller stripped all this footage of any dialogue, and added in its place recordings of hands clapping and a choir singing. She also tinted each clip a different color, further adding to the otherworldly feel of the work.

Indeed, it often seemed as though Hiller wanted to transport her viewers to another dimension or headspace by cinematic or aural means. Aliens and UFOs were a repeated point of interest. Her video installation Belshazzar’s Feast, the Writing on Your Wall, which has taken a variety of forms throughout the years, features a TV set playing footage of flames inside a moodily lit mod living room. Included within the piece is the sound of a whispering voice reading a report from a British newspaper in which a person alleges that aliens are beaming messages about the end of the world through televisions, but people can’t hear them. And for her sound installation Witness (2000), some 400 speakers play recordings of people describing their encounters with aliens.

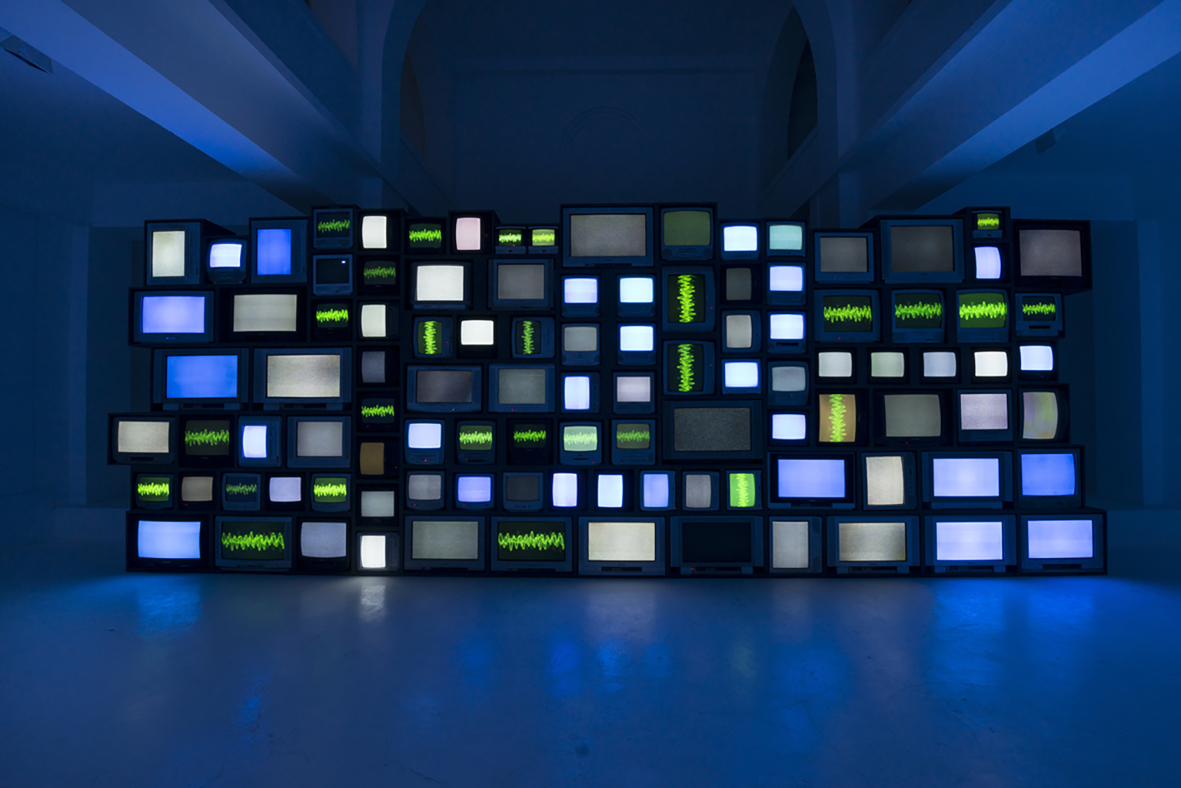

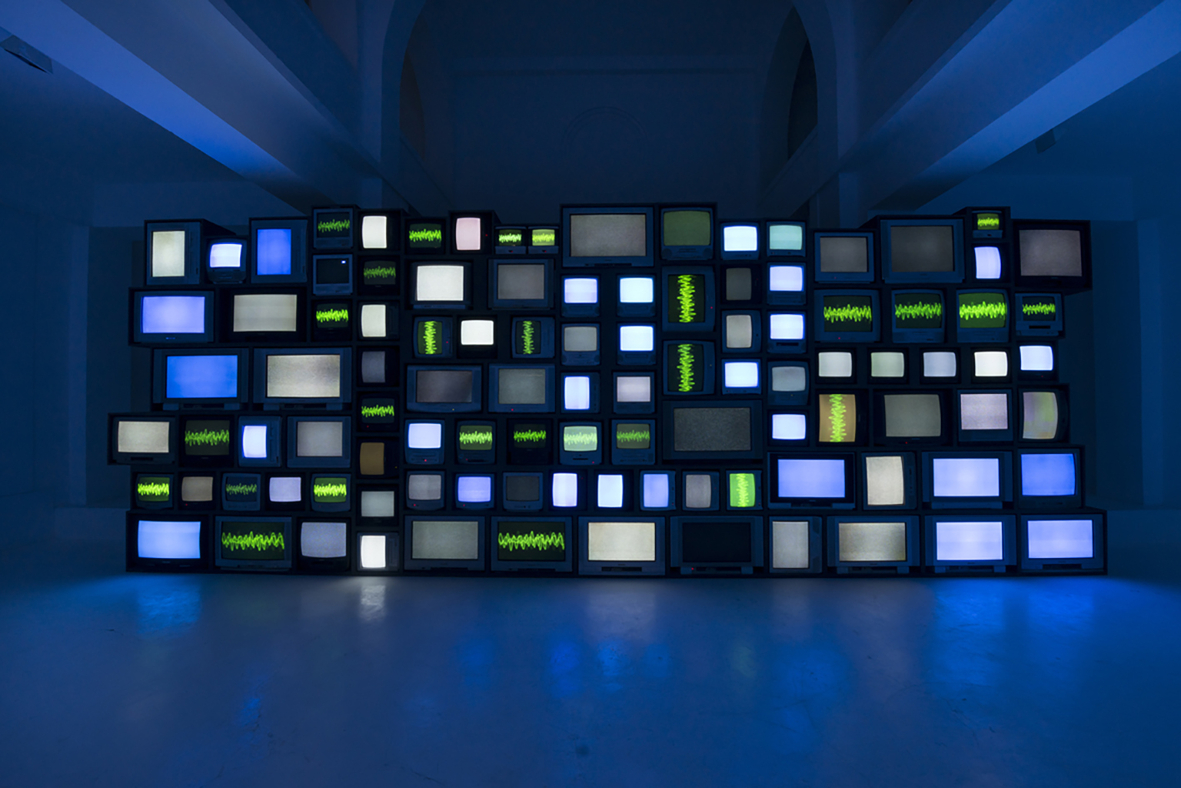

Susan Hiller, Channels, 2013, video installation with sound.

©SUSAN HILLER/COURTESY LISSON GALLERY/OH DANCY

Occasionally, her investigations carry a quiet poetic touch, as in her video piece The Last Silent Movie (2007/08), shown at Documenta 14, in 2017, which features a blank screen and the sounds of people speaking in dead or dying languages, accompanied by English subtitles so that they are alive, in at least some partial sense, for as long as the video screens.

Susan Hiller, Homage to Marcel Duchamp: Aura (Blue Woman), 2017, Giclée print.

©SUSAN HILLER/COURTESY LISSON GALLERY/JACK HEMS

Hiller was born in 1940 in Tallahassee, Florida. As a teenager, she came across a Margaret Mead brochure about anthropology, and decided early on that she wanted to go into that field. Once she got married, during the 1960s, she moved to London, where she was put in touch with a number of British Conceptualists and Minimalists. Her work was seen as being too warm by some in her cohort. “The artefacts that interested me seemed to be things that were overlooked or discarded, kitsch or embarrassing,” she said in 2005. “I liked to take them seriously.”

Occasionally, her work evidenced an anthropologist’s sensibility. Working on commission for the Freud Museum in London during the 1990s, Hiller began a project called From the Freud Museum, which groups unlike objects—reproductions of aboriginal cave paintings in Australia, essays on HIV/AIDS, ceramics, records—in archival boxes. The work was inspired by the Freud Museum’s emphasis on displaying the psychoanalyst’s personal belongings alongside artworks and antiquities from his collection, and was meant to expose cultural and historical biases integral to Western civilization.

Over the years, Hiller’s work was surveyed frequently, at such venues as the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the Castello di Rivoli in Turin, Italy.

In the last decade of her career, Hiller began applying her interests to the digital sphere. Her 2008 project Homage to Marcel Duchamp: Auras involved taking aura photographs—pictures meant to capture their sitters’ energy—from the internet, altering them, and then re-presenting them in the form of a grid. She spoke of the project, an allusion to a 1910 Duchamp piece, as being about spirits and modern technology. “It’s interesting that the subject dissolves in a cloud of colored light,” she told Artforum. “On the one hand, the image has a history, and on the other, it is enigmatically definitive of how we see ourselves in the digital age. You know, we are pixels; we’re light.”

[ad_2]

Source link