[ad_1]

Simon Dinnerstein, The Fulbright Triptych, 1971–74, oil on wood panels, 79 ½ x 168 in., framed and separated. Click to enlarge.

COLLECTION OF THE PALMER MUSEUM OF ART, PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY

‘It’s all there in Proust—all mankind!” Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer once told an interviewer. Breyer explained, “Proust is a universal author: he can touch anyone, for different reasons; each of us can find some piece of himself in Proust, at different ages.”

Those comments came to my mind this summer while I was at the Arnot Art Museum in Elmira, New York, standing in front of The Fulbright Triptych, a sprawling, astonishingly detailed painting that the Brooklyn-based artist Simon Dinnerstein worked on unceasingly between 1971 and 1974. Like In Search of Lost Time, it is a sui generis masterpiece, a world onto itself—and one that has earned a devoted following even though it has spent much of its life in storage.

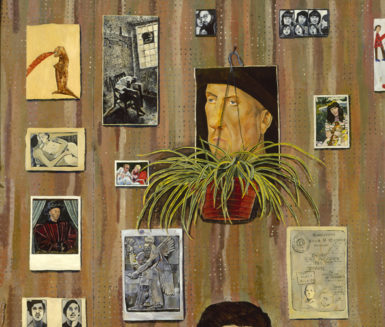

Detail of Simon Dinnerstein’s The Fulbright Triptych, 1971–74.

COLLECTION OF THE PALMER MUSEUM OF ART, PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY

The work’s subject sounds simple enough: a view of the artist’s studio outside of Kassel, Germany, where he was living in the early 1970s with his wife, Renee, and studying printmaking on a Fulbright grant. The tools of his trade sit on a large black table beneath windows that look out onto modest homes, a tranquil, Ferdinand Hodler-like landscape behind them.

But Dinnerstein painted each element of the room—its roughed-up floor, its drab pegboard walls—with such humble care that the work stands as a kind of monument to close looking. It exemplifies how making, and even viewing, art can be a meditative act.

The 14-foot-wide and roughly 6-and-a-half-foot-tall work is, among many other things, a self-portrait and a family portrait. Dinnerstein appears in one side panel, stone-faced, with a big beard, about 30 years old, while Renee appears in the other, also deadpan, holding their young daughter, Simone, who was born in Brooklyn while her father was midway through work on the piece.

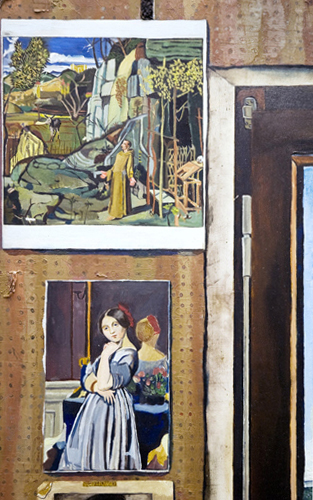

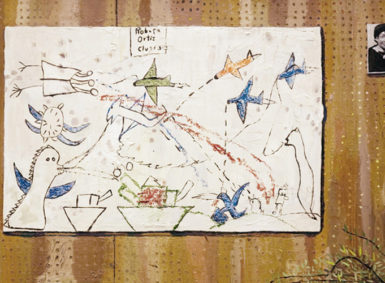

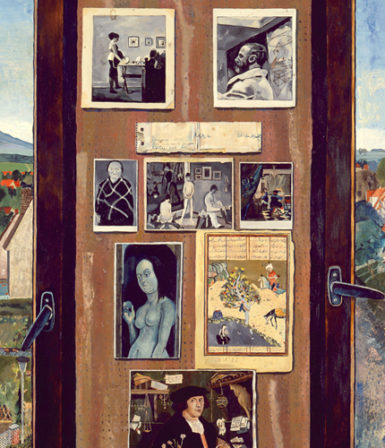

Dozens of little images and texts that line the walls of the scene are the work’s coup de grâce. They include Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s portrait of the beguiling Comtesse d’Haussonville from circa 1845, a classic black-and-white Larry Clark photo of a couple making out in the back of a car, an ancient Assyrian stone relief, and Jan van Eyck’s mysterious Baudoin de Lannoy (from around 1437) peering out from behind a quotidian houseplant. Still more artifacts include charming children’s drawings (one depicting the Dinnerstein family) and a famous snippet of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Altogether, they show Dinnerstein studying and celebrating his influences—everything that made him the artist and person he had become. He assembled his own personal museum in a single artwork, and it teems with connections between pictures, panels, and epochs. The longer I looked at it, the richer and stranger it seemed.

Detail of Simon Dinnerstein’s The Fulbright Triptych, 1971–74.

COLLECTION OF THE PALMER MUSEUM OF ART, PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY

Dinnerstein, now 75, told me in a phone interview last year that he hadn’t made a painting in years back when he began work on The Fulbright Triptych, and recalled the moment when inspiration came to him in his German studio. “I don’t know why, but I moved back and sat back about 8 feet,” he said. “I looked at the scene and it was quite striking and quite appealing. I saw it as a painting.”

“In retrospect, one wonders how you could actually do this,” he said of his ambitious project, which involved meticulously copying so many famed works from across the ages, experimenting with disparate styles and techniques. “I had moments of doubt, but I really was so obsessed with working it out that I was OCD—a candidate for a mental hospital.”

Chance had delivered Dinnerstein to that moment. He had originally hoped to win a Fulbright scholarship to Spain, to study with the painter Antonio López García, but instead was awarded support to travel to his second choice, Germany. “We had some really, really genuine mixed feelings about going,” he said, in light of his Jewish heritage. But he and his wife “took a deep breath and decided to go” in 1971.

At the time, the city of Kassel was still recovering from the devastation of World War II. “If the Allies had planes with bombs left over, they dropped them on Kassel,” Dinnerstein said. The triptych can be regarded as a testament to how culture and identity endure though trauma, and how histories and civilizations can be reconstructed through art.

After returning to New York in 1974, Dinnerstein kept at work on the painting, and one day the Manhattan dealer George W. Staempfli saw it and offered to pay him a stipend toward its completion. “It was like the gods sent a messenger, and so I had to do it,” the artist said, sounding wistful. “Every month this money came. I had a job working one evening a week, and every other day all I did was work on this painting.”

Detail of Simon Dinnerstein’s The Fulbright Triptych, 1971–74.

COLLECTION OF THE PALMER MUSEUM OF ART, PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY

It finally debuted at the Staempfli Gallery in 1975, and earned a rave from John Russell in the New York Times, who proposed that a museum should buy it. But it wasn’t until 1982 that it was acquired by the Palmer Museum of Art at the Pennsylvania State University, where it has sometimes been off view for stretches.

In 2011, though, that changed, with the German Consulate General in New York hosting the triptych in a Dinnerstein exhibition that also featured some of his later works—psychologically loaded paintings and drawings with doses of Magical Realism. In another rave, Roberta Smith lamented that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had not bought the work. That same year, he published The Suspension of Time, an anthology of essays on the work, and the painting has since traveled to shows in Columbus, Missouri, and Elmira, New York, where I saw it. It’s now on view at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno through January 6, before heading across the country for a show of Dinnerstein’s art at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey in Summit, which opens February 22.

Detail of Simon Dinnerstein’s The Fulbright Triptych, 1971–74.

COLLECTION OF THE PALMER MUSEUM OF ART, PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY

In mind of the newfound attention for his three-panel painting, Dinnerstein cited F. Scott Fitzgerald’s quip that “there are no second acts in American lives,” and continued, “For the last, I would say, seven years, this has been a second act.”

He sounded excited and fulfilled. Still, the work he completed 45 years ago in some ways eludes him, as it has eluded so many others. He spent countless hours making it, and he’s seen it in every show that it has ever been in. “Even after all of that, I can’t take this painting in,” he said. “It’s beyond what I can take in.”

[ad_2]

Source link