[ad_1]

Tala Madani, The Audience (still), 2018, single-channel animation (color, sound), 16 minutes, 8 seconds.

©TALA MADANI/COURTESY 303 GALLERY, NEW YORK

This year marked the 50th anniversary of the release of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which proposed countless new possibilities for filmmaking. In her 1969 essay “Bodies in Space: Film as ‘Carnal Knowledge,’ ” Annette Michelson, who died this year at 95, singled out one of the movie’s many innovations as paramount: the famous cut between a shot of a bone flung up in the air by a prehistoric primate and the image of a spaceship gliding through space eons later. Michelson called it “the most spectacular ellipsis in cinematic history” and declared that, in a single edit, Kubrick managed to bring together everything that had ever happened to humankind.

Many artists this year linked the past, the present, and the future. Arthur Jafa connected slavery to depictions of blackness in recent blockbuster movies in his video essay APEX (2013), which was shown at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York. Trisha Baga, in a video installation at Greene Naftali, brought new technological innovations into conversation with prehistoric environmental happenings.

Many more connections between the past and the present—and the future still to come—follow below in my ranked list of favorite screen-based works I saw this year in galleries, museums, theaters, computers, and wherever else.

Sondra Perry, IT’S IN THE GAME ‘17 or Mirror Gag for Vitrine and Projection, 2017, digital video projection in a room painted Rosco Chroma Key Blue, color, sound (looped).

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND BRIDGET DONAHUE, NEW YORK

IN GALLERIES

1. Sondra Perry at Bridget Donahue: The centerpiece of Sondra Perry’s remarkable exhibition was the video IT’S IN THE GAME ’17 or Mirror Gag for Vitrine and Projection, which took up the story of Perry’s brother—a college basketball player whose image was used by the video-game developer EA Sports without his permission—and went on to include meditations on the digitization of museum holdings and the theft of artifacts by European colonialists. The work served as a tremendous statement about cultural and conceptual appropriation, and about the exploitation of bodies, particularly those belonging to black Americans, in the digital sphere.

2. Jason Loebs at Ludlow 38: This show was bathed in an acrid shade of orange-yellow light of a kind used in labs where photographs are developed. Under this lighting was a group of faux marble stelae and a series of terrific photographs featuring iPhones reflecting stills from movie scenes in courtrooms. Loebs portrayed the way information is in transit these days—between screens and the real world, between sheets of documents and Word docs, and between people who share images and data constantly.

3. “Evidence” at Metro Pictures: Josh Kline curated this sharp group show, which touched on capitalism’s deadening effects on many Americans’ day-to-day experience and the disillusionment many have faced since the economic recession in 2008. With works by Kline, Paul Pfeiffer, Gloria Maximo, and more, “Evidence” was a downcast but gripping affair.

Trisha Baga, Mollusca & The Pelvic Floor, 2018, two-channel projection: 2D video and 3D video, ceramics and various materials.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GREENE NAFTALI, NEW YORK

4. Trisha Baga at Greene Naftali: Trisha Baga continually reveals herself to be one of the most exciting young video artists working today, and with this show she offered further proof of her imagination. Alongside a menagerie of gloopy-looking ceramics, she showed Mollusca & The Pelvic Floor (2018), a complex 3D video installation about natural cycles and circular forms, with cryptic narration controlling a device reminiscent of an Amazon Alexa. What a knockout.

5. Tala Madani at 303 Gallery: Most of the works in Tala Madani’s latest outing didn’t involve screens, but I couldn’t get enough of her new animation The Audience, which mocks our obsession with violent masculine movies. The piece made me laugh out loud—how could you not giggle when an aroused guy gets beaten to death with his own distended erection? But I also found it disturbing—one memorable set piece involves three men watching a projected film of a mob pushing a poor figure down three escalators until his body falls apart.

Bruce Nauman, Contrapposto Studies, i through vii, 2015/16, seven-channel video (color, sound, continuous duration).

©2018 BRUCE NAUMAN/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/PHOTO: COURTESY THE ARTIST AND SPERONE WESTWATER, NEW YORK/THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, JOINTLY OWNED BY THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, ACQUIRED IN PART THROUGH THE GENEROSITY OF AGNES GUND AND JO CAROLE AND RONALD S. LAUDER; AND EMMANUEL HOFFMANN FOUNDATION, ON PERMANENT LOAN TO ÖFFENTLICHE KUNSTSAMMLUNG BASEL

IN MUSEUMS

1. Adrian Piper and Bruce Nauman at Museum of Modern Art: MoMA gave these two video-art pioneers the ample space they deserve. Adrian Piper’s retrospective, the most important exhibition of the year (now on view at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles), took on themes related to sexism, xenophobia, and racism, while MoMA’s Nauman blow-out, which traveled from the Schaulager in Switzerland and spills over into MoMA PS1, offered many possibilities for how video can be used to represent the human body under surveillance.

2. John Akomfrah at New Museum: I have long admired Akomfrah’s ability to create constellations with distant histories—to connect, say, the story of Olaudah Equiano, an enslaved Igbo who bought his freedom in the 18th century, and the melting ice caps of the Arctic Sea—so I was glad a U.S. museum finally surveyed his hypnotic films. The show was a bit small, with just four of his transcendent works on view in the main presentation (four more films by Akomfrah and his now-defunct Black Audio Film Collective also screened separately at the museum), but that leaves room for another institution to stage more. Let’s hope for that—and maybe a BAFC survey, too—in the years to come.

Friederike Pezold, Die neue leibhaftige Zeichensprache (The New Embodied Sign Language), 1973–76, four digitized videos.

HAMBURGER KUNSTHALLE

3. “Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995” at MIT List Visual Arts Center: This show, which also traveled to SculptureCenter in New York, surveyed video art before projectors turned cheap and lightweight, and offered a fascinating view into how a variety of artists made monitors a part of their sculptures. The artist selection was terrific—Shigeko Kubota and Nam June Paik, side by side!—and the works included were rich and incisive.

4. “An Evening with Camille Henrot” at Museum of Modern Art: I still lament the fact that Camille Henrot’s Palais de Tokyo exhibition never traveled from Paris to the U.S., but at least we got a taste of it with this one-night event for which the French artist screened a few of her videos. Included among them was Saturday (2017), a 20-minute showstopper that focuses on various forms of rest and relaxation, from praying at church to watching the news. It also ponders the ways that screens and digital images offer some sick sense of comfort—and with some of the most stunning uses of 3D in recent memory.

5. Juan Antonio Olivares at Whitney Museum: In a lovely one-work exhibition, Juan Antonio Olivares showed his 2017 video Moléculas, which features a 3D animation of a teddy bear that seems to mull over its own existence, in a melancholy exploration of how online representations of people can be haunted by a sense of disembodied loss. I was disappointed this work wasn’t talked about more.

Suspiria (still), 2018, 152 minutes.

COURTESY AMAZON STUDIOS

IN THEATERS

1. Suspiria: Luca Guadagnino’s reimagining of Dario Argento’s cult classic about a witches’ coven at a European dance school is less a remake than a gut renovation, with the action moved to 1970s Berlin against a the backdrop of radical leftist activism. In Guadagnino’s hands, Suspiria became a weird, arty metaphor for the reemergence of fascism in seemingly liberal times. The film is visceral and hypnotic, with all kinds of haunting images—crumpled bodies, hexed modernist dance routines, blood-drenched rites—that linger.

2. Roma: Alfonso Cuarón outdid himself with this small-scale epic about a Mixtec houseworker in 1970s Mexico. Thanks in part to its lush black-and-white cinematography (skillfully lensed by Cuarón himself), Roma overwhelms. It’s about the people who ensure that, in spite of all kinds of destruction—whether in the form of political revolutions or natural disasters—some things remain the same for the wealthy elite.

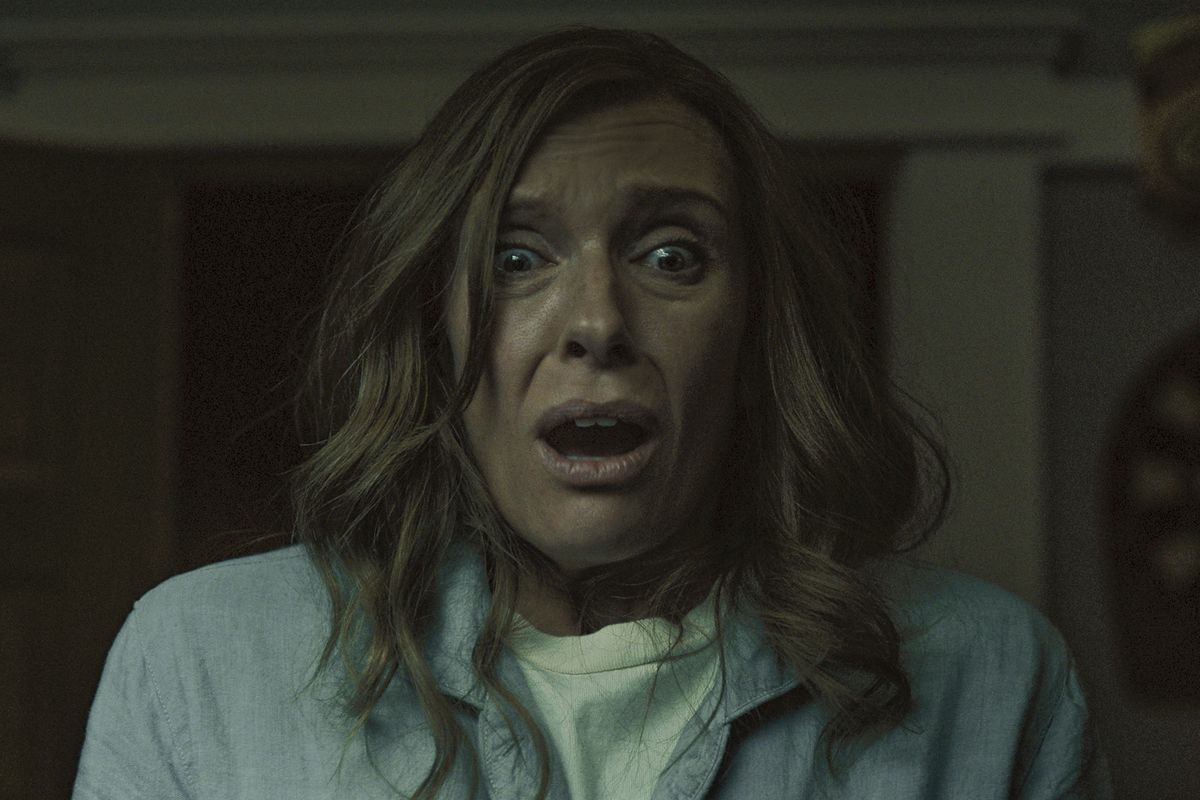

Hereditary (still), 2018, 127 minutes.

COURTESY A24

3. Hereditary: Ari Aster’s Bergmanesque story of one suburban family’s collective crack-up over the death of a grandmother is truly disturbing. It might lose some viewers when it shifts direction in the second half, but it held my interest—and went on to scare the crap out of me. Toni Collette, whose contorted, screaming face frequently fills the screen, turns in an all-time great performance here.

4. Madeline’s Madeline: Performance is the subject of the latest film by Josephine Decker, who has also worked as a performance artist. The film focuses on a mixed-race teenager with an undisclosed mental illness who falls in with an experimental theater troupe. The crew’s white director takes a liking to the titular protagonist and starts trying to control her psyche. This bizarre, unsettling film focuses on the relationship between performers and those who control them—and the twisted power dynamics that play out behind the scenes.

5. 24 Frames: The conceit of Abbas Kiarostami’s final film is simple—24 still images made to move by a combination of digital and analog means. Kiarostami, who died at 76 in 2016, went out with a masterpiece about how film makes photography and other art forms come alive. The movie concludes with one of the great endings: a long take featuring an unidentifiable person asleep at his or her desk, with a shot of a couple kissing from the film The Best Days of Our Lives playing in slow-motion on a computer.

The Americans (still), 2018.

COURTESY FX

ON MY LAPTOP

1. The Americans: Friends tell me I talk too much about this incredible TV series, but permit me to hold forth about it one last time. In its sixth and final season, The Americans reached new heights and cemented its reputation as one of the great television shows of any era. Take it as a metaphor for the immigrant experience or as a sob story about a crumbling marriage—either way, it was suspenseful and achingly sad.

Eva and Franco Mattes, Riccardo Uncut (still), 2018, 87 minutes.

COURTESY THE ARTISTS

2. Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries: For the past two decades, Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries has been making terrific Flash-based animations filled with text that recalls a mixture of propaganda and corporate language. Earlier this year, Hong Kong’s soon-to-open M+ museum acquired the duo’s 500-work archive. Such an acquisition is historic—it’s rare that institutions add major web-based projects to their holdings—and I’d love to see more art museums take on such efforts as this.

3. Eva and Franco Mattes’s Riccardo Uncut: This ingenious work involved the artist duo of Eva and Franco Mattes buying one man’s phone for $1,000 and editing his pictures and videos into a nearly 90-minute-long video. The project, which was commissioned by the Whitney, broaches all sorts of knotty issues related to how digital technology helps us construct our memories—and how it exposes our private lives.

4. Toilets With Threatening Auras: I’m obsessed with this Twitter account that assembles pictures of menacing-looking potties. It really speaks to how even the most banal objects seemed evil in 2018.

5. Porpentine Charity Heartscape’s The Shape You Make When You Want Your Bones to Be Close to the Surface: Commissioned for the show “I Was Raised on the Internet” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, this work is a text-based video game that explores how traumas leak into the digital sphere. I won’t spoil it, but death plays a major role, in ways that prove both tender and terrifying.

Hey, I just wanted to get another look at this A Star Is Born meme.

COURTESY WARNER BROS.

HONORABLE MENTIONS

Memes about A Star Is Born, all of them (I liked the movie just fine, but the memes are another matter entirely); Jibade-Khalil Huffman’s sublimely edited video installation at the Kitchen; Burning, Lee Chang-dong’s mysterious thriller about class warfare in South Korea; Arthur Jafa’s work about blackness at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise; Pose, Atlanta, Vida, and Dear White People, four TV shows that bring to the fore tough issues related to representation and identity in stylish ways; “Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018” at the Whitney, which boasts a superbly restored Nam June Paik installation; Cici Wu’s elegant and odd film installation at 47 Canal; Bogosi Sekhukhuni’s explorations of African technological companies at Foxy Production; Homecoming, a TV series about wartime trauma reminiscent of 1970s paranoid thrillers; Pati Hill and Barbara T. Smith’s experiments with Xerox machines at Essex Street and Andrew Kreps Gallery, respectively; Ethan Hawke’s star turn as an existentially tortured priest in First Reformed; the tight Jack Smith retrospective at Artists Space and Metrograph; and Mission: Impossible—Fallout, for its utterly insane action sequences.

[ad_2]

Source link